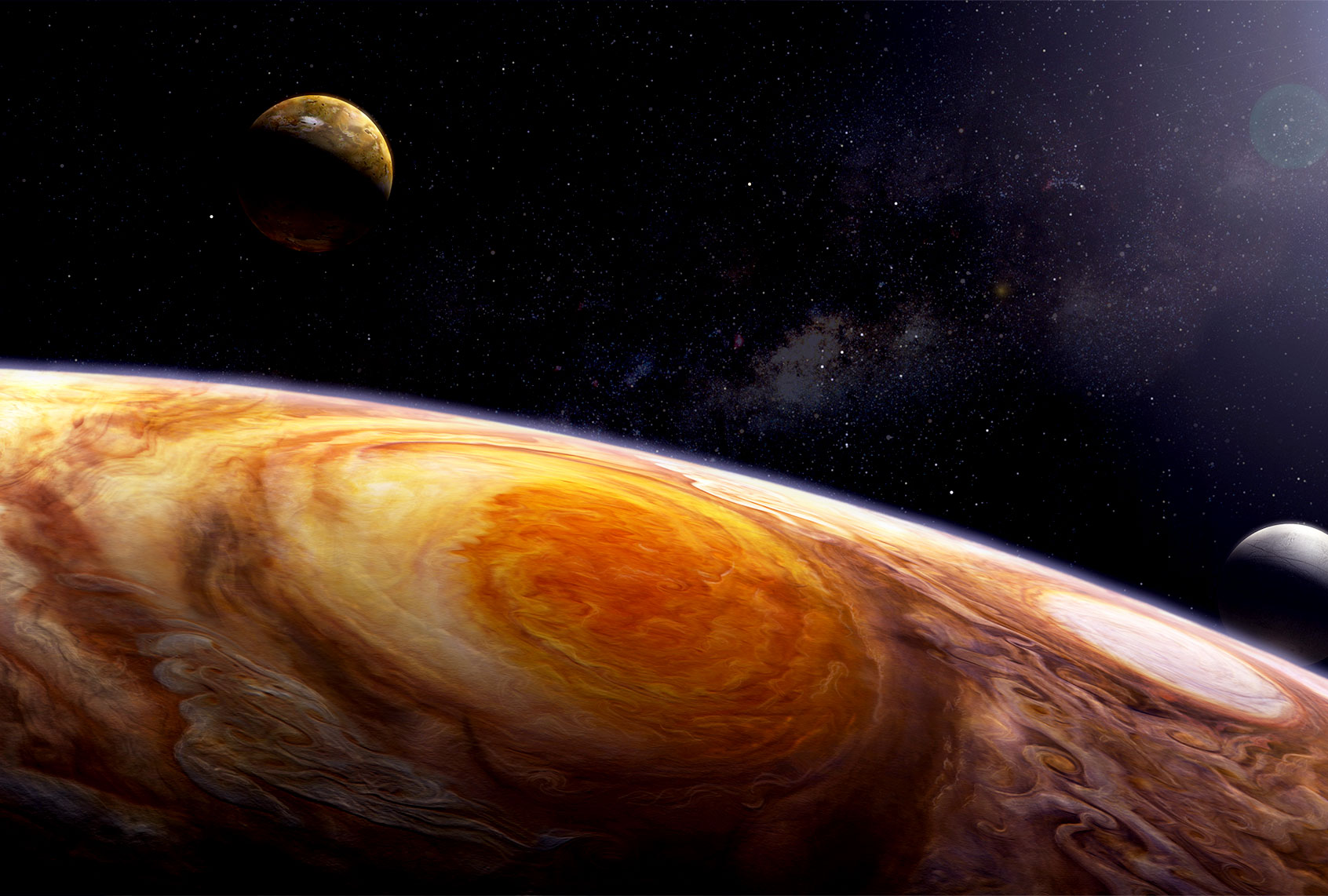

Unlike our ephemeral weather features on Earth, Jupiter’s storms last years, even centuries. The gas giant’s Great Red Spot, a swirling eddy around 10,000 miles wide, has existed for as long as humans have been observing Jupiter through telescopes — since 1665, meaning this storm has lasted at least 356 years. This ongoing storm in Jupiter’s southern hemisphere consists of crimson-colored clouds spinning nearly 400 miles per hour in a counterclockwise loop. The storm has changed in shape and size since it was first observed in detail in the 1800s — and with recent technological advancements, scientists have been able to make more detailed observations about this strange storm’s savage winds.

Now, a recent analysis of data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Hubble Space Telescope revealed something peculiar about the Great Red Spot. Specifically, the average wind speed within the outer boundaries of the storm (known as a high-speed ring) have increased about 8 percent over the last 11 years.

For context, a typical tropical cyclone on Earth can be as wide as 1,240 miles; the storm that comprises the Great Red Spot is nearly 9,941 miles in width. Hurricane speeds on Earth max out at about 190 miles per hour, compared to 400 miles per hour on Jupiter. Unlike Earth hurricanes, the Great Red Spot appears like a wedding cake from the side thanks to its tiered higher clouds.

“When I initially saw the results, I asked ‘Does this make sense?’ No one has ever seen this before,” said Michael Wong of the University of California, Berkeley, who led the analysis published in Geophysical Research Letters. “But this is something only Hubble can do. Hubble’s longevity and ongoing observations make this revelation possible.”

According to the analysis, the change in wind speeds measured amounts an increase of around 1.6 miles per hour per Earth year. The data will help scientists puzzle together a clearer understanding of what’s happening on Jupiter.

“We’re talking about such a small change that if you didn’t have eleven years of Hubble data, we wouldn’t know it happened,” explained Amy Simon of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, who contributed to the research. “With Hubble we have the precision we need to spot a trend.”

In order to observe the small, yet significant change in wind speed, Wong took a new approach to better analyze the data from Hubble. Each time Hubble observed data, he used a specific software to track tens to thousands of wind vectors, meaning the direction and speeds of the winds.

“It gave me a much more consistent set of velocity measurements,” Wong explained. “I also ran a battery of statistical tests to confirm if it was justified to call this an increase in wind speed. It is.”

But what does the increase in speed mean?

“That’s hard to diagnose, since Hubble can’t see the bottom of the storm very well. Anything below the cloud tops is invisible in the data,” Wong said. “But it’s an interesting piece of data that can help us understand what’s fueling the Great Red Spot and how it’s maintaining energy.”

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.