Among the many reasons people watch shows from other countries is to enjoy how their cultures view the world, and what that paradigm tells us about ourselves. Right now, Netflix's "Squid Game" is commanding global attention with a show and tell that's fascinating a huge, rapt audience. According to the streaming service's own report, the South Korean thriller may become the company's most watched title ever. For various reasons the public should take that declaration with a beach's worth of salt; still, it's an impressive performance, especially considering the K-drama's hyperviolence.

How bloody is it? By the end of the first episode more than 250 people are gunned down in an enclosed arena for losing a round of "Red Light, Green Light." Nobody who signed up to play realizes that being eliminated means death. They are all led believe they're partaking in simple playground games like this for a shot at winning 45.6 billion Korean won, the equivalent of around $39 million in U.S. currency. It sounds like buying a lottery ticket, only with improved odds since each challenge involves participating in simple childhood fun instead of leaving the outcome solely up to chance. But losers have zero chances of dodging a bullet to the brain or heart; that part of the deal takes people by surprise.

What follows is more shocking – or it would be, if every participant weren't being crushed under a mountain of debt. In the immediate aftermath of the massacre, the survivors vote on whether to leave the game. But their bleak financial circumstances lead many to reconsider and return, deciding that risk of a bloody, swift death is preferable to a hellish lifetime of digging out of an inescapable financial hole.

It really is an excellent distillation of how predatory capitalism works.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Few people watching "Squid Game" are likely to be familiar with that term. (Heck, most of them probably don't even realize they're watching a K-drama.) But on a planet where the average income of the top 10 percent is 38 times higher than the average of the bottom half, plenty of folks are living with it. That counts anyone living paycheck to paycheck and doing their best to stay level on the rickety balance beam that is our economy, which is most people. Predatory capitalism is the beast snarling at their back and the one waiting at the bottom of the pit, jaws open wide.

Allegorizing this concept also distinguishes this series from other "deadly game" titles such as "Battle Royale" or "The Hunger Games." It's actually closer in spirit to Netflix's adaptation of "Alice in Borderland," although the terror at the center of that series and the manga it's based upon is existential. The enemy in "Squid Game" is material and relatable.

Series director and writer Hwang Dong-hyu has said in a previous interview that he designed the tale as a critique of capitalism, demonstrated by the desperation massive indebtedness stokes in each character. But for clarity's sake we should establish that predatory capitalism takes the principle to a darker place in that it accepts exploitation and brute domination as part of as necessary evils.

This encompasses so much more than simply owing money to a creditor, legal or otherwise. It normalizes a vicious kind of Darwinism in everyday interactions, driving our scramble to rise, increase our status and outdo others. Never does it acknowledge that very few people ever grow wealthy enough to achieve invulnerability, but maintaining that lie is necessary for predatory capitalism to continue feeding apex devourers.

Hwang writes this principle into each of his central characters, but it even informs the smallest details of the production. Even death, most often delivered by a faceless workers in pink jumpsuits who shoot losing contestants in the head, is packaged to resemble a gift: bodies are lifted into black coffins with pink bows on the lid before being anonymously disposed of.

Long before we see that, however, we meet lovable layabout Seong Gi-hun (Lee Jung-jae). Gi-hun is goofy and has a broad, friendly smile, but he's also a deadbeat dad who leeches money off of his elderly mother to sate his gambling addiction.

Emphatic capitalist striving has also ensnared Gi-hun's childhood pal Cho Sang-woo (Park Hae-soo), but Sang-woo had determination, intelligence and luck on his side, having attended a university to become an investment banker. Being 650 million in the red brings him to the games, the result of betting and losing his wealth alongside that of his clients . . . and his mother's.

Next to him North Korean defector Kang Sae-byeok (Jung Ho-yeon) looks virtuous, mostly because she has absolutely nothing to her name. Her goal is to make enough money to house her brother, who she's left at an orphanage, and to find her mother who was deported back to North Korea. She survives as a pickpocket, desperate to escape the gangster she used to work for, Jang Deok-su (Heo Sung-tae). Even he owes other criminals who'd prefer to take their payments out of his flesh.

On and on it rolls, a wheel driven by a merciless system and steered by hidden forces. An entire episode is devoted to a group of hedonistic VIPs who bet on the players, each wearing golden masks shaped like a predatory mammal, a raptor, or an avatar of fortune (a stag) or strength (an oxen).

A version of these heartless villains exists in every type of "deadly game" story, but Hwang intentionally plays up the callous stupidity of his shadowy titans. They spew terrible, obvious dialogue, misattribute cliched quotes and wager on the lives of others based on lewd jokes revolving around the number 69. Nothing about them indicates they deserve to be where they are more than the working class folks dying for their entertainment.

But these puppet masters aren't the sole destroyers in this story. They're simply the ones too far removed from their humanity to care about what they're doing to the little folks, using the ones who share breathing space with them as refreshment dispensers or furniture.

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK)

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK)

With few exceptions, each of the centrally developed characters is some form of low-level monetary carnivore or scavenger, showing how predatory capitalism encourages us to cannibalize each other – even family. Gi-hun doesn't only take the meager cash his mother offers him. He also guesses her PIN and drains her bank account. Sang-woo lies to his mother about his life and the fact that he's financially ruined her, leaving her under the impression that he's traveling for work when he's actually hiding out from the police after stealing from his own clients.

The only extensively developed main characters who don't appear to be preying on others are Abdul Ali (Tripathi Anupam), a Pakistani worker whose employer kept his wages from him and who steals back what he's owed, and Oh Il-Nam (Oh Young-soo), an elderly man with a brain tumor.

Just like the rest, they're also being stalked, and view the games as the only way to get clear of what's hunting them. Then again, the game-makers selected every participant for reasons beyond what they owe. They target their weakness. Before Gi-hun, Sang-woo and the other hundreds of contenders gain an invitation to the game they enter a contest with a mysterious man (Gong Yoo, "Train to Busan") who persuades them to let him slap their faces for a chance to win pocket change.

Being broke isn't enough, you see. In order to submit to the games, a person must also be broken.

And this makes Gi-hun's story much sadder. Later in the series we find that he was fired from a solid factory job, then wiped out when the small business he attempted to launch afterward collapsed. That means Gi-hun followed every line of in the bootstrapping myth to the letter by working hard and playing by the rules, and he ends up in serious hock anyway.

One of the darker observations I read online about the appeal of "Squid Game" theorizes that at some point in the pandemic, many people might have accepted such an offer. Who could blame them if they did? One of the half-truths the games' masked Front Man (Lee Byung-hun) promises is that everyone in these games receives a fair shot, that nobody is discriminated against due to age, class or gender.

It's the meritocracy lie, gamified. Everyone who isn't part of the 1% receives assurances that the system is fair, right? Few being mauled by its gears want to acknowledge or even understand how impressively rigged the system is. Centralizing that lie is the way this story depicts carnivorous financial systems working exactly as they're supposed to, by dangling the prize just out of reach but close enough to see it and keep telling ourselves we'll get there. Even Gi-hun tries to reassure Sang-woo that he can recover from his debt without risking his life, insisting that his business school degree means he can always earn money, that he's better off that most. That simply isn't the case out in these streets.

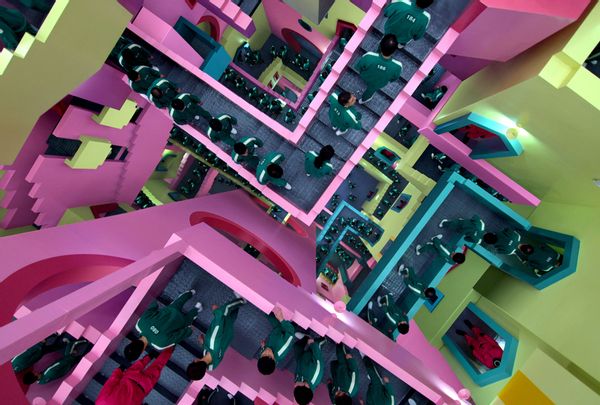

Inside the game, though, Sang-woo thinks has better a shot. The weird sets he and everyone else walk through are an aesthetic bonus, externalizing the nightmarishness of their excessive financial burden. Contestants pass restless nights in spartan quarters resembling a school gymnasium. The maze of hallways and pastel staircases dividing that place and competition staging areas marry the geometrics of an M.C. Escher drawing to the innocent pinks, yellows and blues of a Barbie Dream House.

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK/Netflix)

Squid Game (YOUNGKYU PARK/Netflix)

Then there's the misdirect of the games' innocence: One might look at the competition mounted to entertain the VIPs as a variation of "Floor Is Lava," except falling to the floor in this show actually kills people.

"Squid Game" refers to a South Korean playground contest that has specific rules, but whose play revolves around roughhousing and viciousness. Anyone who's played such games in childhood knows that making it past a goal line isn't always the point. Sometimes the object is to bruise the other kid – all in good fun, of course.

Upsizing that violence for adult players escalates the physical and psychological ruthlessness commensurate to the life and death stakes. To say a viewer learns to deal with the brutality of "Squid Game" is not a sufficient assurance for the squeamish, nor should it be.

But the bullets and blood may also obscure some of Hwang's key questions about humanity and societies, such as: Which is more dangerous to our collective health, desperation or greed? And which is more corrosive?

Hwang may have originally asked this in the context of South Korea's economic disparity, but the fact that the show is No. 1 the U.S., the U.K. and many other countries proves the universality of his message. Nothing is lost in the translation, whether you watch "Squid Game" with the subtitles on or dubbed. (Subs are the way to go, by the way.) And the director acknowledges this by having one of VIPs blithely mention in passing that the South Korean games are the best ones, implying similar lethal competitions are being played in other countries around the world.

Of course they are.

"Squid Game" is currently streaming on Netflix.

Shares