The butterflies in your stomach, the sweat on your palms — they're your friends. Our ancestors evolved those responses to keep us safe. You just need to direct that energy into something more productive than midnight doomscrolling. You need some good anxiety.

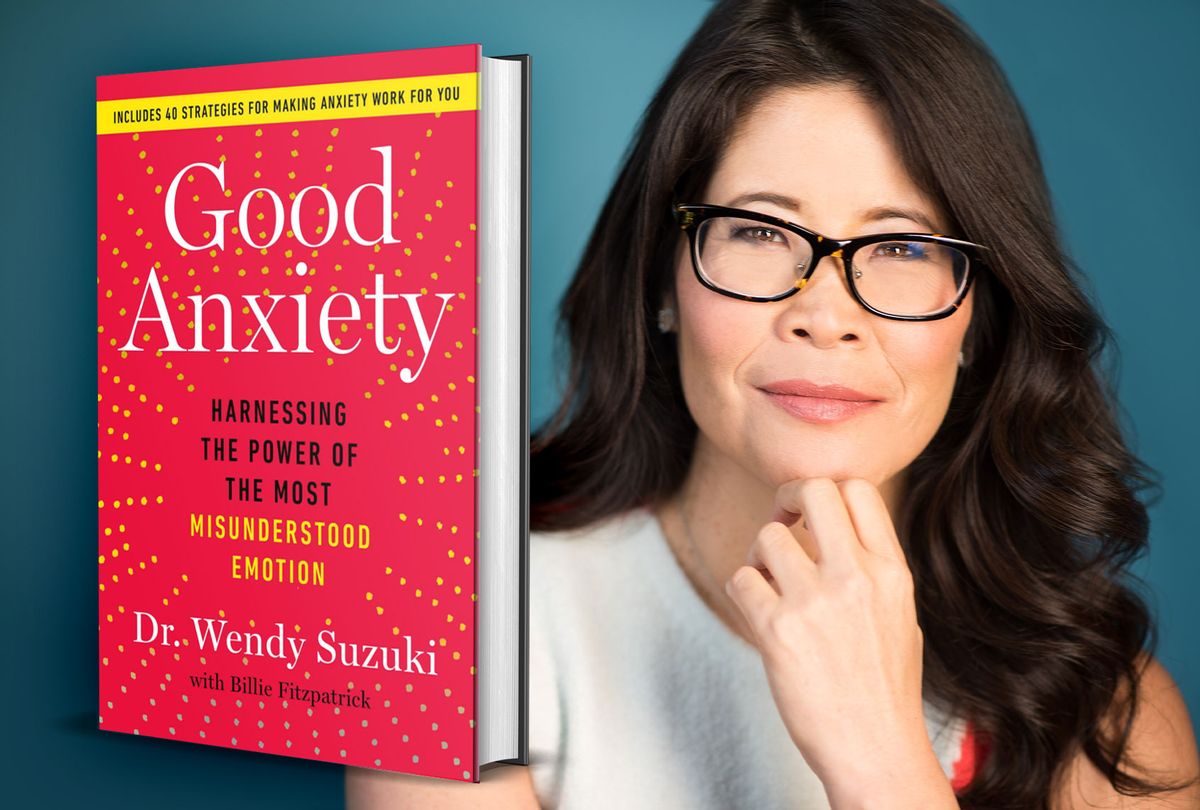

Dr. Wendy Suzuki knows that your complicated, amazing brain can be a real downer sometimes, and she'd like to help you put it to better use. In her latest book, "Good Anxiety: Harnessing the Power of the Most Misunderstood Emotion," the neuroscientist explains the reasons our brains react the ways they do and why anxiety can be a secret superpower, and offers tools for a real world practice of healthier emotional regulation. Salon spoke to Suzuki recently about our epidemic of anxiety, and how we can learn to "worry well."

As usual, this conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

How many of us are dealing from anxiety?

Basically everybody. Every single person has some form of anxiety. It's so important to start with that, because there's still a shame and embarrassment. You don't want to say it out loud, because it sounds like you have a mental illness and that sounds really bad. But everybody has feelings of anxiety, and even more so right now.

There's everyday anxiety, which we all deal with to a certain extent. Then there's the kind that really, really interferes. How do we distinguish a tough period in life from something more serious?

The easiest way to separate out clinical levels of anxiety (where you must go see a medical professional) is when it is truly debilitating. This is not like, "Oh, this is so annoying." Annoying is not debilitating. Debilitating is: you cannot go outside, you can't go to work, you can't interact with your family, you can't have relationships.

Those numbers before the pandemic of number of people diagnosed with that level of anxiety was almost 20% of the population, so 40 million people. There are a lot of people like that out there — and that number has been estimated to have gone up about 30% in particular subpopulations. African-Americans, young millennials — that is people in their early twenties — and adolescent girls seem to be suffering particularly from clinical levels of anxiety these days.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

There are things that all of us, regardless of our level of time, money, social constructs can be doing with our anxiety. You use the phrase, "Worry well."

We have to get away from the idea that anxiety is a weight around our necks that is just inevitable, we have to deal with it, it's always there and there's nothing good about it. That is so wrong. Anxiety and the underlying physiological stress response evolved to protect us. Is that important? Yes. It protects us from outside threats that were there 2.5 million years ago. Now those threats are mainly internal, the threats come from the newsfeed, from the pandemic updates, from the weather updates every hour. So for everybody out there saying, "I don't feel protected at all from my anxiety," The answer is, because the volume is way too high.

Anything at too high a level is not good any more. We've all of us, collectively, reached too high level of anxiety. It can no longer be protective. But it's a very different idea that "I want to get rid of it" versus, "I want to get it to the level where it can help me." That's a very different mindset and that's one of the big ideas that I hope everybody will take away.

This is what I love to teach in my neuroscience classes, neuroscience that makes a difference. This comes from our basic understanding of the physiology and neurobiology of the brain. It was evolved there for a reason, not just to annoy us. It evolved to help us move, help us fight or flight. It can come back to that really, really valuable level, but we need to turn the volume down. That is the very first step.

What really happens inside of our brains when we do the work, when we practice changing our behavior, changing our thoughts?

The best and fastest way to do that is simply to activate the part of our nervous system that evolved to help us relax. It's called the parasympathetic nervous system. All Neuroscience 101 students learn about it, and they're like, "Memorize this, this is what it does, go on."

But it's doing something really important for all of us these days. It is decreasing our heart rate, decreasing respiration and it's bringing blood from the muscles, from our fight or flight response back to our digestion and reproduction. I can't control in my mind my blood going into my digestive system, but I can slow my breathing down.

Deep breathing is good. You are literally stimulating your relaxation parasympathetic nervous system by this conscious act of deeply inhaling with intention and deeply exhaling. That can help start the entire process of relaxation in your body. It can help when you're in the depths of an anxiety attack, it can help when you're just starting.

The best thing is that I talk a lot to parents and kids that are worried about going back to school. Parents, you can do it in the middle of a conversation when it's starting to get a little bit tense and just take a moment to breathe while the other person is talking. Kids can do it standing in line, sitting in class, they just need a little guidance. How do we do it? What does slow mean? But it's very, very powerful.

That's the first step, activate your parasympathetic nervous system. Let me go to brain plasticity. Brain plasticity is our brain's ability to adapt to the environment. A lot of the tips in the book are shifts of mindset. How do you shift your mindset? We already talked about one big one. Anxiety is not so bad that we have to get rid of it and throw it out the door. It was evolved to protect us. That is a mindset shift, and that helps you. How do we learn that? We learn that with our hippocampus, important for learning new facts and events. We can consolidate that piece of information by thinking about all the ways that perhaps our own anxiety have helped us.

If I don't have butterflies before a TV interview, or before that big lecture, I'm not going to go to give a good talk. That is my definition of good anxiety, and was one of the pillars that I started writing this book on.

How does that manifest for you? Maybe you're not a speaker, but maybe you have those butterflies before a really important conversation or a really important test, where you're able to use that to harness that energy that it created to help you perform better. That is at the heart of good anxiety, which is very empowering. It's like, "I could use this thing that's always around anyway and I could make myself actually perform better if I could harness it."

To go through the process of, "This is what I feel, this is signaling something to me and then here are the actions that I can take."

I think of this in steps. What do we do with this knowledge that anxiety could be protective? First step, dial down the volume. Step two is another one of these lost ideas —anxiety is protective. Think about those uncomfortable emotions that come up with anxiety — fear, worry, anger. Those are the ones that feel like that weight around your chest and you just want to kick them out the door and never see them again. That is the big mistake. We are humans and we have a huge wide plethora of emotions. If we lived only in the happy ones and we were just Teletubby-happy all the time, that would not be a fulfilled life.

We have these uncomfortable emotions for a really important reason. They tell us what's important. They give us sadness when something important has gone away for whatever reasons, which is life. The second step is to realize that those negative emotions that are on high volume right now are valuable. What can they tell me about what I value in my life? What is there too much? What is not there enough? Learn from that because that'll make you realize, "I see why it's protective. It's protecting me by showing me what is important using these uncomfortable emotions that really get my attention. These are important messages.

So much of the messaging has been, let me show you how to be happy, but let's just focus on the happiness. I love happiness. Happiness is great. But the thing that I learned the most in writing this book and researching is that I found myself making friends with my own anxiety and those uncomfortable emotions. Yes, it's not a warm and fuzzy friend. My anxiety is a prickly friend, but sometimes those prickly friends have your best interests at heart and are saying, "Look at this right now. What is it really telling you?" But if I'm so anxious that I can't think of anything, I can't use my prefrontal cortex, then I can't appreciate that.

You talk about concepts that are hard for many people to get — doing things like increasing your compassion, slowing down. For a lot of us right now, we're in this moment of deep scarcity and fear. You see many of us retreating into our fears.

So, let's talk about what happens to us as a species and happens in our brains and why, when we were feeling that kind of anger and reactivity and fear — that is, when we have to reach deep and find those spaces of compassion.

You've brought up one of the gifts or superpowers that comes from anxiety, which I know is very counter-intuitive. Let's translate that into the current situation in fear or whatever you're fighting for. If you turn that fear towards the outside, you can recognize that in others. Even reaching out empathetically and saying, "This is so hard because I want to share but this is so hard. What do you think that we should do?" starts to bring the wall down.

From a neuroscience point of view, empathy and doing something for others, helping somebody else in a difficult fearful situation, releases dopamine in the brain. We know this from studies. So you're not only practicing empathy and compassion for others, but you're doing something that will reward yourself with higher levels of dopamine, which we all need when we deal with these kinds of situations anyway. That is the gift of empathy that comes from anxiety.

Come for the empathy, stay for the dopamine.

This book is the book that it became because of chapter four, the resilience chapter. I had a tragedy in my life and dealt with these really horrible, uncomfortable, saddest emotions I've ever had because of the death of my father and my brother I couldn't write the book on anxiety. I took a little break but came out of it having experienced these difficult feelings and with a reminder from a workout coach, that with great pain comes great wisdom. I thought, I'm a different person on the other side, but I've learned a lot about love and appreciation that was theoretical.

Because of that experience, I thought, every bout of anxiety is a pain, it's a difficulty. What if I try and squeeze out all the wisdom from that, what would that do? That's how all the gifts or superpowers came out. They would not have been written this way if I hadn't gone through that. I did explore my own anxiety but I explored from the perspective of, I must get something good out of them. What is that, that I can get out of it? It was therapeutic for me because I needed to pull out good stuff from this book that I was writing right after this terrible event.

I want to ask you about change, and about really believing and buying into this idea that we can change. There is a certain pride that comes from being a stressed out person, who's too busy to meditate and too anxious to slow down. How do we take that step back and say, "I don't have to be this way. I can change and that I might feel better"?

My optimism around change comes from my lifelong study in neuroscience of brain plasticity. The very first time I realized I wanted to become a neuroscientist was the first day of my freshman year. I walked in on a classroom of the woman who discovered brain plasticity at UC Berkeley. She reminded me and the other students in the class that the human brain is the most complex and amazing structure known to humankind, in part because it can change. It was evolved to be able to change, and learn, and adapt to the environment. She spent her career figuring out how to positively change the brain with things like environmental enrichment — a lot of exercise, social interaction. Our brains can do that. We've evolved to be able to really survive.

I'm talking about the brain. If you ask me as a neuroscientist, can people do this? Can people learn to shift their mindset to adapt to these different things that will decrease their anxiety? Like breath work, like exercise? Absolutely. Absolutely. I come from the school of thought that I'm very optimistic, that everybody can do this. They can take all the tools in the book and change everything from their mindset to their breathing patterns when in situations of anxiety. Instead of having it be this thing that you just can't wait to get rid of, wouldn't you like to be able to optimize your anxiety response and pull out all of that energy and use it for things you want to use it for?

Shares