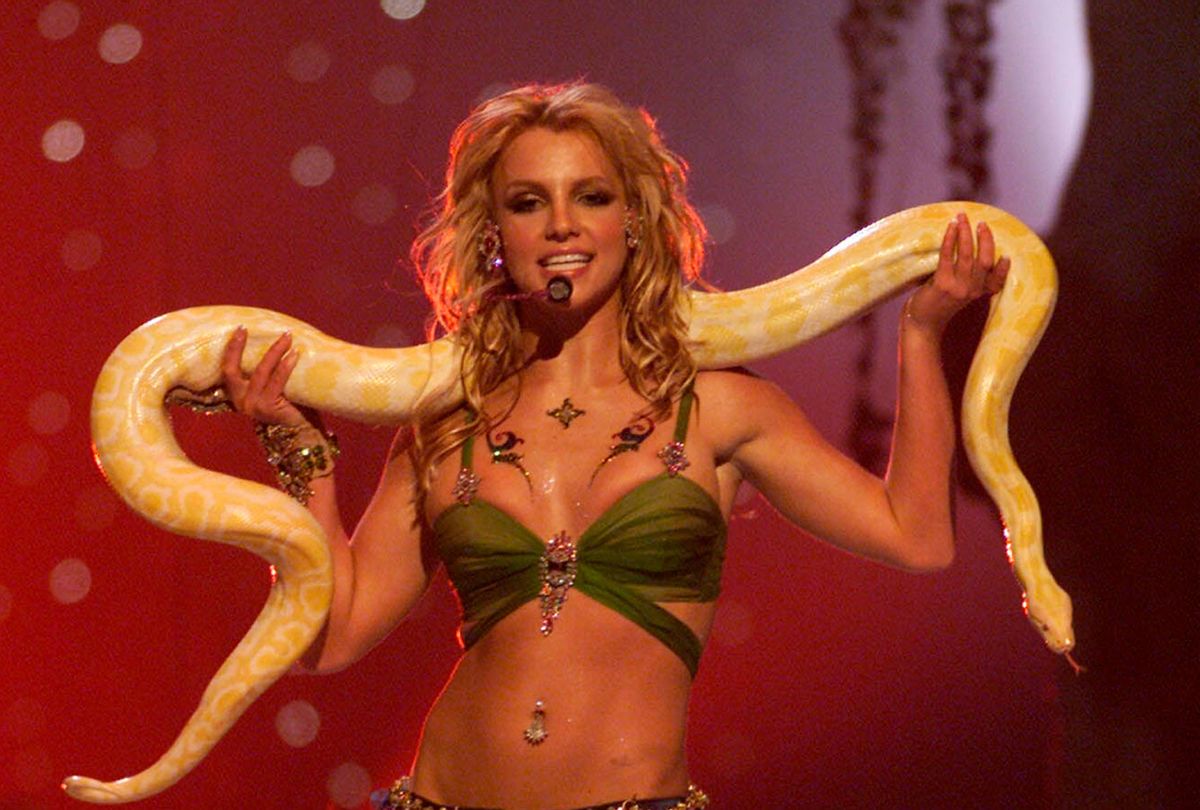

When Britney Spears last went before a judge, in June, she bristled as she told of being forced into psychiatric care that cost her $60,000 a month. Though the pop star's circumstances in a financial conservatorship are unusual, every year hundreds of thousands of other psychiatric patients also receive involuntary care, and many are stuck with the bill.

Few have Spears' resources to pay for it, which can have devastating consequences.

To the frustration of those who study the issue, data on how many people are involuntarily hospitalized and how much they pay is sparse. From what can be gathered, approximately 2 million psychiatric patients are hospitalized each year in the United States, nearly half involuntarily. One study found that a quarter of these hospitalizations are covered by private insurance, which often has high copays, and 10% were "self-pay/no charge," where patients are often billed but cannot pay.

I am a psychiatrist in New York City, and I have cared for hundreds of involuntarily hospitalized patients. Cost is almost never discussed. Many patients with serious mental illness have low incomes, unlike Britney Spears. In an informal survey of my colleagues on the issue, the most common response is, "Yeah, that feels wrong, but what else can we do?" When patients pose an acutely high risk of harm to themselves or others, psychiatrists are obligated to hospitalize them against their will, even if it could lead to long-term financial strain.

While hospitals sometimes absorb the cost, patients can be left with ruined credit, endless collection calls and additional mistrust of the mental health care system. In cases in which a hospital chooses to sue, patients can even be incarcerated for not showing up in court. On the hospital side, unpaid bills might further incentivize a hospital to close psych beds in favor of more lucrative medical services, such as outpatient surgeries, with better insurance reimbursement.

Rebecca Lewis, a 27-year-old Ohioan, has confronted this problem for as long as she has been a psychiatric patient. At 24, she began experiencing auditory hallucinations of people calling her name, followed by delusional beliefs about mythological creatures. While these experiences felt very real to her, she nevertheless knew something was off.

Not knowing where to turn, Lewis called a crisis line, which told her to go to an evaluation center in Columbus. When she drove herself there, she found an ambulance waiting for her. "They told me to get into the ambulance," she said, "and they said it would be worse if I ran."

Lewis, who was ultimately diagnosed with schizophrenia, was hospitalized for two days against her will. She refused to sign paperwork acknowledging responsibility for charges. The hospital attempted to obtain her mother's credit card, which Lewis had been given in case of emergencies, but she refused to hand it over. She later got a $1,700 bill in the mail. She did not contact the hospital to negotiate the bill because, she said, "I did not have the emotional energy to return to that battle."

To this day, Lewis gets debt collection calls and letters. When she picks up the calls, she explains she has no intention of paying because the services were forced on her. Her credit is damaged, but she considers herself lucky because she was able to buy a house from a family member, given how challenging it would have been to secure a mortgage.

The debt looms over her psyche. "It's not fun to know that there's this thing out there that I don't feel that I can ever fix. I feel like I have to be extra careful — always, forever — because there's going to be this debt," she said.

Lewis receives outpatient psychiatric care that has stabilized her and prevented further hospitalizations, but she still looks back on her first and only hospitalization with scorn. "They preyed on my desperation," she said.

While it is likely that many thousands of Americans share Lewis' experience, we lack reliable data on debt incurred for involuntary psychiatric care. According to Dr. Nathaniel Morris, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California-San Francisco, we don't know how often patients are charged for involuntary care or how much they end up paying. Even data on how often people are hospitalized against their wishes is limited.

Morris is one of the few researchers who have focused on this issue. He got interested after his patients told him about being billed after involuntary hospitalization, and he was struck by the ethical dilemma these bills represent.

"I've had patients ask me how much their care is going to cost, and one of the most horrible things is, as a physician, I often can't tell them because our medical billing systems are so complex," he said. "Then, when you add on the involuntary psychiatric factor, it just takes it to another level."

Similarly, legal rulings on the issue are sparse. "I've only seen a handful of decisions over the years," said Ira Burnim, legal director of the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. "I don't know that there is a consensus."

People who have been involuntarily hospitalized rarely seek a lawyer, Burnim said, but when they do, the debt collection agencies will often drop the case rather than face a costly legal battle.

The media will be obsessed with Britney Spears' next day in court, expected to be Sept. 29. She will likely describe further details of her conservatorship that will highlight the plight of many forced into care.

Others won't get that kind of attention. As Rebecca Lewis put it, reflecting on her decision not to challenge the bills she faces: "They're Goliath and I'm little David."

Dr. Christopher Magoon is a resident physician at the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry in New York City.

Shares