Extreme urban heat exposure has dramatically increased since the early 1980s, with the total exposure tripling over the past 35 years. Today, about 1.7 billion people, nearly one-quarter of the global population, live in urban areas where extreme heat exposure has risen, as we show in a new study released Oct. 4, 2021.

Most reports on urban heat exposure are based on broad estimates that overlook millions of at-risk residents. We looked closer. Using satellite estimates of where every person on the planet lived each year from 1983 to 2016, we counted the number of days per year that people in over 13,000 urban areas were exposed to extreme heat.

The story that emerges is one of rapidly increasing heat exposure, with poor and marginalized people particularly at risk.

Nearly two-thirds of the global increase in urban exposure to extreme heat was in sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia. This is in part because of climate change and the urban heat island effect – temperatures in urban areas are higher because of the materials used to build roads and buildings. But it is also because the number of people living in dense urban areas has rapidly increased.

Urban populations have ballooned, from 2 billion people living in cities and towns in 1985 to 4.4 billion today. While the patterns vary from city to city, urban population growth has been fastest among African cities where governments did not plan or build infrastructure to meet the needs of new urban residents.

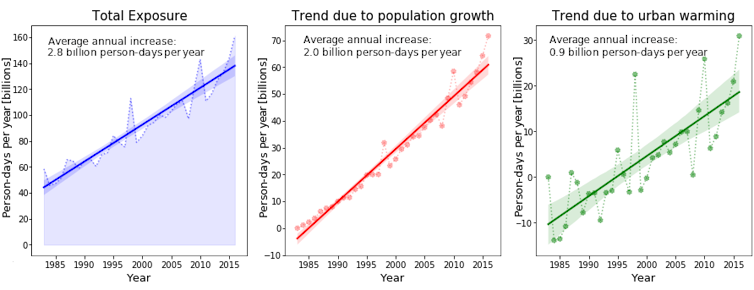

Urban population exposure to extreme heat and the influence of urban warming and population growth. Extreme heat is defined as at least one day with a wet-bulb globe temperature greater than 30 C. Wet-bulb globe temperature takes into account temperature, humidity, wind and radiation to gauge the effect on humans. Tuholske et al, 2021

Climate change is raising the heat risk

It is clear that there is a dangerous interaction of increasing temperatures and rapid urban population growth in countries that are already very warm.

How much worse will it get, and who will be most affected? Chris Funk explores these heat exposure projections for 2030 and 2050 in his new Cambridge University Press book "Drought Flood Fire."

Urban population growth is expected to continue, and if greenhouse gases continue on their rapid growth path, we will see massive increases in heat exposure among urban dwellers. The planet has already warmed just over 1 degree Celsius (1.8 F) since pre-industrial times, and research shows warming is translating to more dangerous weather and climate extremes. We are almost certain to experience another degree of warming by 2050, and likely more.

This amount of warming, combined with urban population growth, could lead to a 400% increase in extreme heat exposure by 2050. The vast majority of people affected will live in South Asia and Africa, in river valleys like the Ganges, Indus, Nile and Niger. Hot, humid, populated and poor cradles of civilization are becoming epicenters of heat risk.

At the same time, research shows that marginalized people – the poor, women, children, the elderly – may lack access to resources that could help them stay safer in extreme heat, such as air conditioning, rest during the hottest parts of the day and health care.

Counting who's at risk

To count the number of urban residents exposed to extreme heat, we used data and models that incorporate advances in both social and physical sciences.

More than 3 billion urban residents live 25 kilometers or farther from a weather station with a robust reporting record. Climate model simulations that estimate past weather were not designed to measure a single person's risk; rather, they were used to gauge broad-scale trends. This means the effects of extreme heat for hundreds of millions of impoverished urban residents worldwide have simply not been documented.

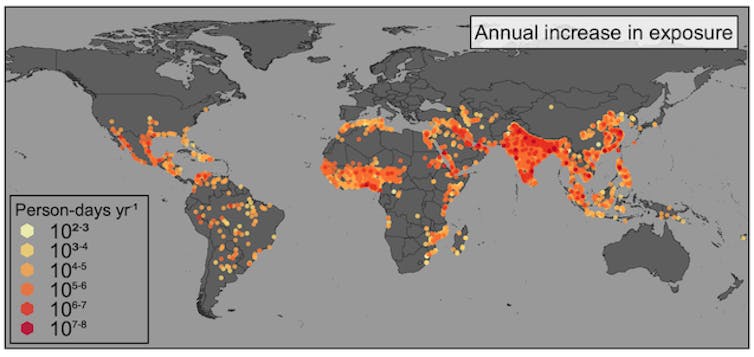

The increase in extreme heat exposure in cities around the world from 1983 to 2016. Tuholske et al, 2021

In fact, the official record states that only two extreme heat events have had significant effects on sub-Saharan Africa since the 1900s. Our results show that this official record is not true.

Reasons for action

Urban population growth itself is not the problem. But the convergence of changes in extreme heat with large urban populations calls into question the conventional wisdom that urbanization uniformly reduces poverty.

Historically, urbanization was associated with a shift in the workforce, from farming to manufacturing and services, in tandem with industrialization of agricultural production that increased efficiency. But in parts of sub-Saharan Africa, there has been urbanization without economic growth. This may be due to post-colonial technological changes that improve health. People are living longer and more children are surviving past infancy thanks to medical advances, but post-colonial governments often don't have or don't mobilize the resources to support huge numbers of people moving to cities.

What worries us is that because urban extreme heat exposure has largely been left off the development policy radar, poor urban residents will have a harder time escaping poverty. Numerous studies have shown that extreme heat reduces labor productivity and economic output. Low-income workers tend to have fewer worker protections. They are also burdened with high costs for food and shelter, and often lack air conditioning.

Steps cities can take

The coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement have amplified demands for greater political and scientific attention to inequality and injustice. Better data that helps to capture the true lived experiences of individuals is a key feature of more integrated and socially relevant climate-health science. Collaborations across scientific disciplines like ours can help governments and businesses accommodate new urban residents and reduce harm from heat.

Implementing early warning systems, for example, can reduce risks if they are accompanied by actions like opening cooling centers. Governments can also implement occupational heat standards to reduce heat risks for marginalized people and empower them to avoid exposure. But these interventions need to reach the people most in need.

Our research offers a map for policies and technologies alike, not just to reduce harm from urban extreme heat exposure in the future, but today.

Cascade Tuholske, Postdoctoral Research Scientist, Center for International Earth Science Information Network (CIESIN), Columbia Climate School, Columbia University; Chris Funk, Director of the Climate Hazards Center, University of California Santa Barbara, and Kathryn Grace, Associate Professor of Geography, Environment and Society, University of Minnesota

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Shares