The September jobs numbers released on Friday suggest that the GOP governors who decided to end federal unemployment payments failed to accomplish their goal of jumpstarting the economy out of its pandemic-era mire — something experts predicted months ago.

According to the Bureau of Labor, employers reported 194,000 new jobs, a far cry from the 500,000-plus expected by analysts. The labor force likewise shrank by 183,000 since August, though unemployment did see a slight dip from 5.2% to 4.8%.

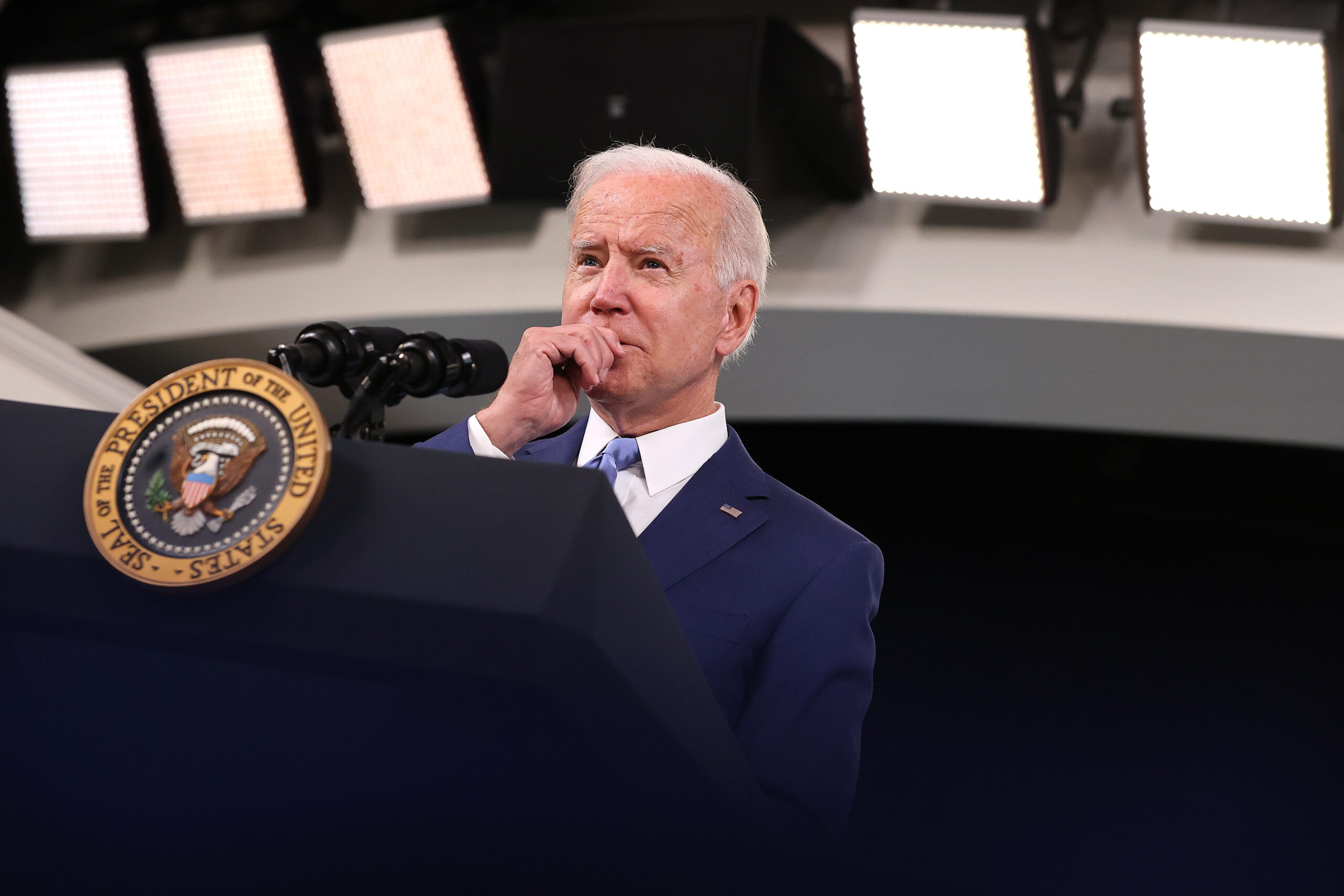

President Biden has pushed back on claims that the numbers indicate a serious level of contraction, stressing that the unemployment rate hasn’t fallen below 5% since the beginning of the pandemic. Biden also noted that the monthly average job growth is still around 600,000 under his watch, suggesting the administration is slowly but surely steering the economy back to health.

“The monthly total has bounced around, but if you look at the trend, it’s solid,” Biden said.

Recently, the debate around monthly job growth has mapped onto distinctly political lines, as Salon’s Brett Bachman reported back in May, when the Department of Labor released a similar batch of less-than-stellar jobs numbers.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

At the time, conservative pundits and politicians aggressively pounced on unemployment benefits, suggesting with scant evidence that Americans were no longer motivated to work, thereby causing a massive “labor shortage.” In the months following, over two dozen Republican governors jumped to end their federal unemployment programs, promising an economic rebound in return.

This week’s numbers, however, appear to fly in the face such promises.

Last month, Axios reported that states that discontinued benefits saw roughly half the job growth enjoyed by states that maintained the program. Neil Irwin, senior economics correspondent for The New York Times, this week echoed a similar sentiment, citing “no surge in participation in the labor force” despite the “labor shortage woes that many business groups” have pushed.

In a Friday analysis, Matt Bruenig, founder of the People’s Policy Project, pointed out the wide discrepancy in the number of people who lost their unemployment benefits in September (about 8 million) and the number of people who acquired work (about 194,000).

“194,000 jobs is equal to less than 3 percent of the people who were removed from the UI rolls in September,” Breunig said. “At this rate, it would take 3.5 years for jobs-added to equal the number of people who lost their pandemic UI benefits.”

It remains unclear precisely why September’s numbers fell so far below analysts’ expectations, but many have speculated that the pandemic continues to hold back economic growth. During the summer, many schools expected to reopen in September, but another surge in COVID-19 cases dashed those hopes, potentially leading to a wave of economic cutbacks.

“All the evidence points toward pandemic [unemployment benefits] not being the main factor,” Nick Bunker, economic research director for North America at the Indeed Hiring Lab, told CNBC. “The best estimate right now is that it’s the pandemic itself.”

According to NPR, the jobs numbers may be artificially depressed because sudden seasonal changes in school hiring.

Some analysts found that the discontinuation of benefits may have even contributed to the underperforming labor market.

Peter McCrory, an economist at JPMorgan Chase Bank, wrote that “the loss of benefits is associated with a modest decline in employment growth, earnings growth and labor force participation.”

Others have speculated that workers are readjusting their professional priorities amid the pandemic. According to a Pew poll, roughly 66% of unemployed Americans have seriously considered switching jobs.

“It’s not just money, sitting on both sides of the scale,” Melissa Swift, global leader of workforce transformation at consulting firm Korn Ferry, told Axios, citing the challenges of working with an understaffed team, juggling parenting with work, or being the only person of color at one’s place of work. “We basically burned out the global workforce over the last year. One of the ways people deal with burnout is switching employers.”