Edgar Allan Poe, in a July 1841 article for Graham's Magazine, wrote that while people tend to think it's a relatively simple thing to create an uncrackable secret code, in fact "it may be roundly asserted that human ingenuity cannot concoct a cipher which human ingenuity cannot resolve." That was easy for him to say. Shortly after his premature death, Poe's friend the Rev. Warren H. Cudworth recalled that the author's ability to "unravel the most dark and perplexing ciphers was really supernatural." The rest of us get stumped sometimes. Here are five codes and ciphers that have stymied human ingenuity for decades, centuries, even millennia.

1. The Voynich Manuscript

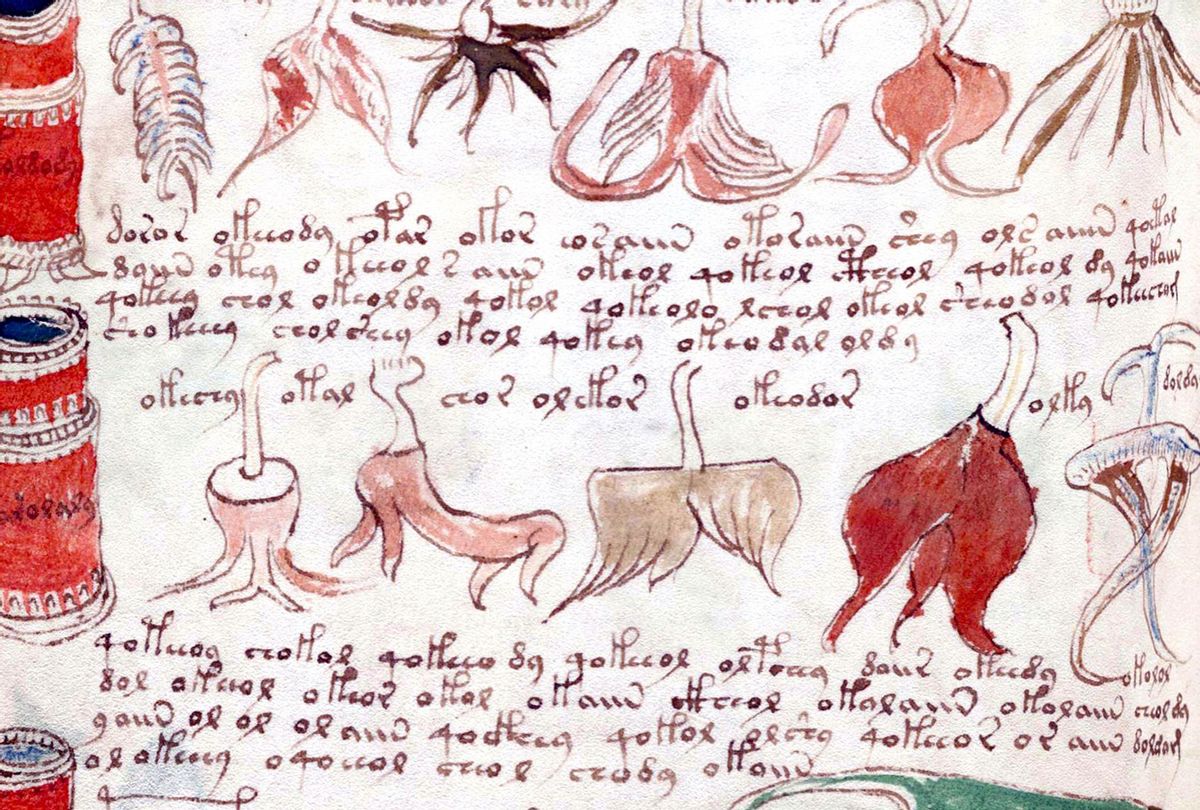

The Voynich Manuscript has been puzzling emperors, antiquarians, and cryptologists for at least 400 years. It's an illuminated manuscript of 240 vellum pages written by an unknown author in an unknown language. Vibrant illustrations of plants and astronomical and astrological charts suggest the volume may be an alchemical, magical, or scientific text. The calfskin pages were radiocarbon dated to between 1404 and 1438. While the iron gall ink has not been dated, since there is no erased earlier writing on the pages, it's likely the manuscript was written around the same time.

Researchers believe Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II (1576-1612) acquired the manuscript in the late 16th century and gave it to his personal physician and pharmacologist Jacobus Sinapius to see if he could make heads or tails of it. He couldn't. Neither could Czech alchemist Georg Baresch, Bohemian physician Johannes Marcus Marci, and Jesuit polymath Athanasius Kircher. After Kircher got the book from Marci in 1665, the manuscript disappears from the historical record until 1912 when antique book dealer Wilfrid Voynich found it in a chest of books the Jesuits were trying to sell at the Villa Mondragone in Frascati, Italy. Voynich would dedicate the rest of his life to deciphering the manuscript. Although he failed, at least his efforts secured him the naming rights.

They also garnered him posthumous accusations of fraud as some people believed the whole book was a hoax devised by Voynich himself. Radiocarbon dating put paid to that theory, as the odds of anyone finding that much fresh, unused 15th-century vellum to cover with fantastical writing and drawing are slim to none. Professional codebreakers in both World Wars and one Cold one tried their hand at cracking the Voynich code without success. (You can read Mental Floss's story about recent attempts to crack it here.)

It's not just the writing that has proven impossible to crack: some of the drawings are ciphers, too. There are 113 unidentified plant species depicted in the manuscript, and nobody knows what the female nudes striking curious poses in bodies of water or with odd pipe systems are supposed to mean.

Do you think you're better than the imperial court of Rudolf II, the greatest cryptographers of the 20th century and pretty much everyone else? You can try your hand at cracking the Voynich Manuscript on the website of Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

2. Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 90

In 1896, archaeologists Bernard Pyne Grenfell and Arthur Surridge Hunt discovered thousands of papyrus fragments in a garbage dump outside Oxyrhynchus, Egypt. Preserved by the dry desert heat, the papyri recorded details of daily life (receipts, insurance claims, loan notes, personal letters), fine literature (large sections of lost Euripides plays, summaries of seven lost books by Livy, a poem by Sappho), and scriptures—gospels, both canonical and apocryphal—from the 1st to the 6th century CE.

Papyrus 90 is one of the mundane daily life records, a receipt for a deposit of wheat in the public granary dating to 179-80 CE. What makes it not mundane are the last two lines. They're written in Greek characters like the rest of the papyrus, but they're not Greek words. Grenfell and Hunt noted when they published the papyrus that it wasn't a Graecized version of Demotic script (the Egyptian "document writing" language) either. It appears to be a cryptogram, some wheat deposit intelligence that demanded secrecy.

A transcription of the text is available for the intrepid Greek scholar/cryptographer here.

3. King Charles I and Queen Henrietta-Maria's letter

King Charles I of England had many secrets to keep and many enemies to keep out of his secrets. Much of his correspondence was peppered with ciphers to keep prying Parliamentarian eyes out of his business. Charles's ciphers kept some secrets so ably that historians didn't realize until a few years ago that a.) he ever talked dirty, and b.) he planned "a swiving" (an obscene word for sex) with the redheaded stepdaughter of one of his courtiers while imprisoned in Carisbrooke Castle in 1648.

During the First English Civil War (1642–1646), he and his beloved wife Henrietta-Maria were apart for long stretches. In the beginning, she was in The Hague trying to drum up political support for the Royalist cause and to hock the Crown Jewels to fund her perpetually broke husband's war. By March of 1645, with the tides of war having turned against them, Henrietta-Maria was back in her hometown of Paris.

Throughout their separation, they wrote to each other assiduously, and they weren't whispering sweet nothings. Henrietta was deeply involved in her husband's governance and for all intents and purposes was a continental branch of Charles I's court. These letters were replete with political machinations, military plans, and perhaps most relevantly for a Protestant England that was deeply suspicious of the Catholic Henrietta-Maria, promises to liberalize England's anti-Catholic laws.

On March 5, 1645, Charles sent a new cipher to Henrietta-Maria via a trusted courier named Pooly. A month later in a letter to his wife dated April 8, he used the cipher:

In a word, when I know none better (I speak not now in relation to business), then 3 9 8 270 55 5 7 67 18 294 35 69 16 54 6 38 1 67 68 9 66: thou mayest easily judge how thy conversation pleased me.

[note] The little that is here in cipher is in that which I sent to thee by Pooly.

After the Battle of Naseby on June 14, 1645, Charles and Henrietta's correspondence was confiscated and published by the Parliamentarians. His letter of March 5 was revealed to be something of a bombshell: He authorized her to promise in his name to anyone useful that "I will take away all the penal laws against the Roman Catholicks in England as soon as God shall enable me to do it so al by their means I may have so powerful assistance as may deserve so great a favour and enable me to do it."

So that April cipher could be an expression of affection or intimacy (he probably wasn't talking about swiving her, though), or it could have been a whole other kind of conversation, like some payoff from that promise, that pleased King Charles. We won't know until someone cracks it.

4. The Dorabella Cipher

Composer Edward Elgar may be best known today as the accompaniment to every graduation ceremony with Pomp and Circumstance, but he was also a fan of cryptographic arts. He expressed his ciphering talent in an addendum to a letter his wife wrote on July 14, 1897. The letter was a thank you note to the Penny family at whose home the Elgars had just spent a convivial few days. Elgar had struck up a friendship with the daughter of the family, Dora Penny, and he added a postscript to his wife's letter directed to Dora.

At first glance, it looks like a group of squiggles at different angles reminiscent of the universal comic book symbol for dizziness, but each character is actually composed of one, two, or three semicircles tilted in eight different directions. Dora couldn't crack it, so she put the letter in a drawer for the next 40 years until she published it in her memoirs in 1937. Since then, people have tried to solve the Dorabella Cipher with some pretty wacky results.

Tim S. Roberts thinks he's cracked it with a simple substitution cipher (you can find a PDF explaining his solution here):

"P.S. Now droop beige weeds set in it – pure idiocy – one entire bed! Luigi Ccibunud luv'ngly tuned liuto studio two."

The subject, Roberts believes, refers to an earlier letter or conversation in which Edward and Dora discussed his excessive pruning of his garden. Without this extremely obscure conversation, the solution makes no sense at all, and frankly, even with it, only the first sentence makes sense. He also had to jiggle things to make them fit. Some parts are straight substitution, others require letters to be switched or added. He only glosses over what "Ccibunud" might mean, saying that Elgar loved the Italian composer Luigi Cherubini growing up, and Dora Penny was said to have had a stutter, so Elgar was teasing her over her pronunciation of an Italian composer that apparently she introduced a random d into. There's also no character for the i in studio. He just put that in to make it form a word.

When the Elgar Society held a Dorabella Cipher Competition in 2007 to celebrate Elgar's 150th birthday (and again the next year), none of the solutions were accepted because, although several seemed to be very well reasoned, in the end, "the results read as a disconnected chain of bizarre utterances, such as an imaginative mind could conjure up from any group of random letters." So far all the proposed solutions seem to fall into this category. And there's one final twist: A key created by Elgar in the 1920s—which, according to New Scientist, appeared in an exercise book and "listed the symbols used in the Dorabella cipher matched against the letters of the alphabet"—doesn't yield anything that makes sense.

5. Carrier pigeon NURP 40 TW 194's final message

In 1982, David and Anne Martin found the remains of a bird during the renovation of the fireplace of their home in Bletchingley, Surrey. One of its skeletonized legs had a red plastic capsule attached to it, marking it as a World War II military carrier pigeon that picked the wrong roost on its way to deliver a message and died in the chimney. Inside the capsule was the original coded message — 27 groups of five letters with some numerals at the end — written on a scroll the size of a rolling paper.

AOAKN HVPKD FNFJU YIDDC

RQXSR DJHFP GOVFN MIAPX

PABUZ WYYNP CMPNW HJRZH

NLXKG MEMKK ONOIB AKEEQ

UAOTA RBQRH DJOFM TPZEH

LKXGH RGGHT JRZCQ FNKTQ

KLDTS GQIRU AOAKN 27 1525/6

It took years before anyone in government could be persuaded to take a look at the cipher. In 2010, experts at Bletchley Park, a museum that was the headquarters of British Intelligence's codebreakers during World War II, finally checked it out. They were not able to crack it, but they did discover that it must have been an important missive. None of Bletchley Park's classified MI6 pigeons carried coded messages during the war. Given Bletchingley's location halfway between Normandy and Bletchley Park and just five miles from Field Marshal Montgomery's headquarters at Reigate where the D-Day landings were planned, it's possible that Pigeon NURP 40 TW 194 was carrying very sensitive information indeed.

A few weeks after the story broke, the media reported that Ontario history buff Gord Young claimed to have cracked the code thanks to his great-uncle's World War I Royal Flying Corp aerial observers book. His solution was rough around the edges, however. He wasn't able to decipher some of it, and several of the 27 groups he interpreted as improvised acronyms with no antecedents in the military record. He may have misinterpreted some of the letters—mistaken a U for a W, for instance—and there are some painfully awkward, redundant phrases like "Determined where Jerry's headquarters front posts. Right battery headquarters right here. Found headquarters infantry right here. Final note, confirming, found Jerry's whereabouts." That's a lot of repetitive verbiage to take up space on a cigarette paper.

Bletchley Park didn't think the solution was the right one. Then, the cryptological world discovered that Young had never intended to present an actual answer—he was just trying to help move the process along. So until a World War II codebook is found with a proper key, Bletchley Park doesn't think anyone is going to be able to crack the pigeon's code.

Shares