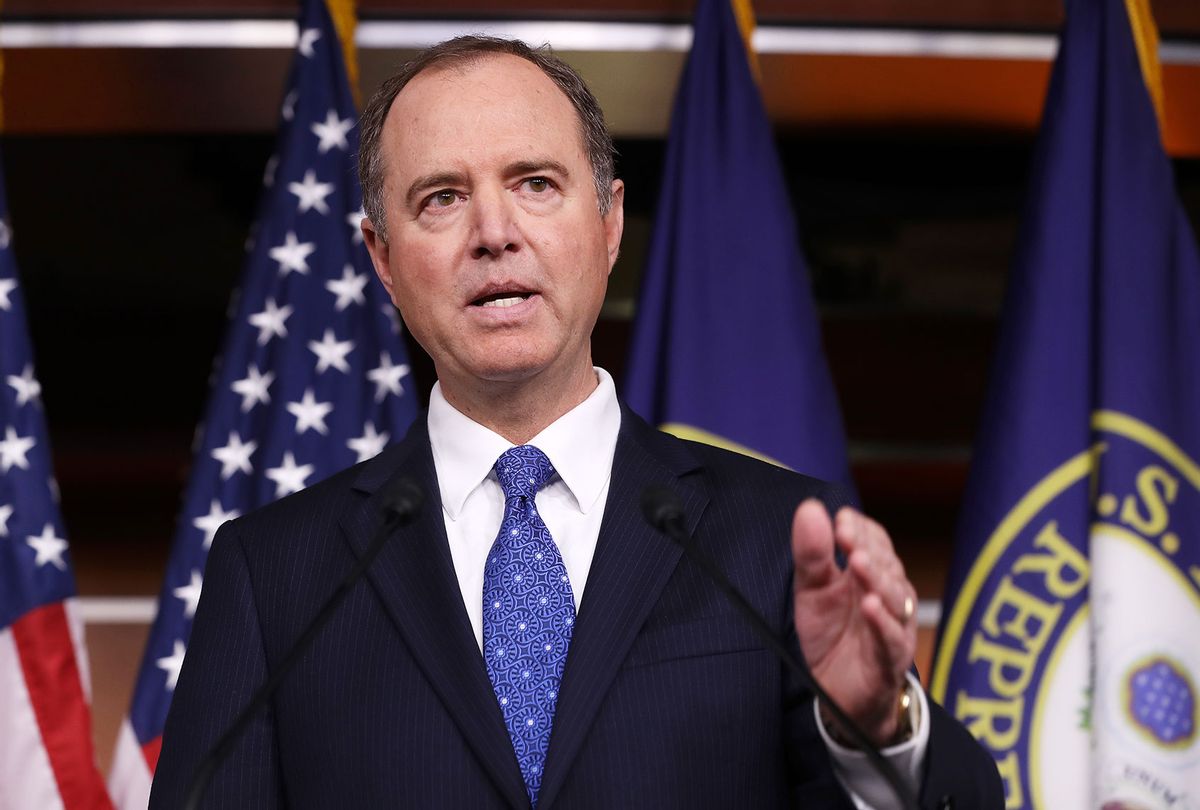

Rep. Adam Schiff, the California Democrat who chairs the House Intelligence Committee, is not the type of person who uses hyperbole just to create soundbites. This former prosecutor has a clear record of sober, measured public rhetoric. So we should all take note when Schiff states that the Department of Justice "should be doing a lot more" when it comes to investigating "any criminal activity that Donald Trump was engaged in," as he did in our recent Salon Talks conversation. In describing the former president's long list of possible or apparent crimes, Schiff said, "I don't think you can ignore the activity and pretend it didn't happen."

I spoke to Schiff about his new book, "Midnight in Washington: How We Almost Lost Our Democracy and Still Could," which is currently at No. 1 on the New York Times nonfiction bestseller list. The clear message Schiff has for America is this: "We came so close to losing our democracy," and that threat is far from over. One of his main motivations in writing the book, Schiff said, is a sense that most people don't "feel a sufficient sense of alarm" over the threat posed by Trump and much of today's Republican Party.

To that end, Schiff opens the book with a gripping retelling of the Jan. 6 act of "domestic terrorism," as the FBI has officially labeled that attack. Schiff says he felt compelled to give that personal account in order "to bring the reader inside that chamber, let them know what it was like to hear the doors being battered, the windows breaking as this mob was trying to get in."

Schiff also discussed what it was like to become a "villain" in Trump's world, as the recipient of a barrage of crude insults launched by the former president and his supporters. Schiff says his sense of humor helped him cope with those slings and arrows, but it was more difficult to face the death threats from those incited by Trump.

Watch the full interview with Schiff here, or read a transcript of our conversation below to hear more about Schiff's warning and call to action. "We don't have the luxury of despair," he told me. "It needs to motivate us to be active."

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Your book opens with a retelling of Jan. 6. You paint a great picture — first of all with your sense of humor, but also of the fear involved and how this was very real. Can you share a little bit about what you went through, and other members went through, with gas masks being handed out and everything else. There are Republicans, as you may have heard, who are trying to depict Jan. 6 as a "tourist visit." So I think the reality needs to be relayed to people about what really went on from the inside.

This is one of the reasons that I wanted to write this down. I wanted to bring the reader inside that chamber, let them know what it was like to hear the doors being battered, the windows breaking as this mob was trying to get in.

I wasn't on the floor the whole time. I had been assigned by the speaker to be one of a handful of managers to oppose the Republican efforts to decertify the election. I really was focused on what I was speaking, what I was saying, what the Republicans were saying. Then I looked up and the speaker was missing from her chair, which struck me because I knew from the preparations she planned to preside the entire time. Soon thereafter two Capitol police rushed onto the floor, grabbed [Majority Leader] Steny Hoyer, and whisked him off the floor so quickly. I remember thinking I'd never seen Steny move that fast.

It wasn't long before we started to get messages from the Capitol police, one after another, of increasing severity, that they were rioters in the building, that we needed to get out the gas masks from under our seats, that we should get prepared to get down on the ground, and ultimately that we needed to get out, and that a way had been paved for us to get out. But I still hung back because there was now a real scrum to get out the door behind the chamber. I still felt relatively calm and was waiting for other people to go ahead. A couple of Republicans came up to me on the floor and said, "Basically, you can't let them see you." One of them said, "I know these people, I can talk to these people, I can talk to my way through these people. You're in a whole different category."

At first, I was kind of touched that they were worried about my safety. And then, you know, the more I thought about it, the more I realized that if they hadn't been lying about the election, I wouldn't need to worry about my safety. None of us would. One of them, when I finally did head to the doors when they were really starting to break glass to get in, and I walked out with a Republican who was holding a wooden post — it wasn't just the Democrats were worried here — he was holding a post to defend himself. And I said to him, because he had a member pin on, but I didn't recognize him, "How long have you been here?" He said, "72 hours. I just got elected."

As you mentioned I used my sense of humor in dark moments to try to alleviate the stress. So he says he'd been there for 72 hours. I looked at him and I said, "It's not always like this." But I tell you, the anger after that day only grew. What I was most angry at was not the insurrectionists who really believed the Big Lie, although I was furious at them too. It was what I described as the insurrectionists in suits and ties, these members that I work with that knew it was a big lie. And even after that brutal attack, when we went back in the chamber with blood still on the floor outside of the chamber, they were still trying to overturn the election. That to me was unforgivable.

To watch it play off from our side, on TV, was stunning. For me, I'm Muslim and the same people on the right had demonized my community for years, saying we knew who the terrorists were and we weren't turning them in because we were soft on terrorism. All of these are lies. Now we actually have Republicans literally defending terrorists by name. You have Donald Trump defending the terrorists, the same man who wanted to ban Muslims from entering the country. I find that hard to process intellectually because it's just so devoid of any decency whatsoever. You mentioned a Republican congressmen saying to you, "These people might hurt you or kill you." They know their base, they know how dangerous they are. So what do we do?

I thought the most powerful speech that day came from a source I was not expecting. It came from Conor Lamb [a moderate Pennsylvania Democrat], this former Marine, generally very soft-spoken. When we went back on the floor after that insurrection to finish the joint session, he talked about how these people had come in and attacked the Capitol and they'd done so because of the big lies being pushed on the other side of the aisle, and how a lot of them had walked in free and walked out free. And he said, "I think we know why they were able to simply walk away."

What he was saying, of course, was that because of their color, because of who they were, because they were white nationalists and not people of color, that they were treated very differently. It was an inescapable truth. This was not just an insurrection against our form of government. It was also a white nationalist insurrection with Confederate flags and people wearing Auschwitz T-shirts. This too was a very sobering thing for me, which was to see where this was coming from and realizing just how far our country still had to go.

In your book, you share things about your family and growing up. One thing stuck out and it's a small thing: You write that in 2010, you were on a plane flight with Kevin McCarthy, a fellow member of the House from California, a Republican. It was before the midterms and you had a conversation. Then he literally goes out and fabricates something, claiming you had told him, "Republicans are going to win this." That was a lie and you went and confronted him. And I was stunned by his reaction, considering this is the man who might be the next speaker of the House. Can you share a little bit about that story?

Yes, and I tell this story because sometimes little vignettes tell us a lot about what people are made of. One of the most frequent questions I get from people is: When you talk to Republicans privately, do they really believe what they say publicly? And the answer, all too often, is no, they don't. They don't believe what they're saying publicly and they will admit it. In this particular case, I was seated next to McCarthy just by coincidence on United Airlines, flying back to Washington. We were having a nothing conversation about who was going to win the midterms. I said I thought Democrats would win. And he said he thought Republicans were going to win. Then the movie started and I was like, "Thank God the movie started."

So we get to D.C. and we go our separate ways and he goes off and does a press briefing and he tells the press, "Oh, Republicans are definitely going to win the midterms. I sat next to Adam Schiff on the plane and even he admitted Republicans were going to win the midterms." The next morning, when that came out, I was beside myself and I went up to him, I made a beeline for him on the House floor. And I said, "Kevin, I would have thought if we're having a private conversation, it was a private conversation. But if it wasn't, you know, I said the exact opposite of what you told the press."

He looks at me and says, "Yeah, I know Adam. But you know how it goes." And I was like, "No, Kevin, I don't know how it goes. You just make stuff up and that's how you operate? Because that's not how I operate." But it is how he operates, and in that respect, Kevin McCarthy was really made for a moment like this, when the leader of his party had no compunction about lie after lie after lie. You say what you need to say, you do what you need to do. The truth doesn't matter. What's right doesn't matter. And someone like that can never be allowed to go near a position of responsibility like the speaker's office.

You also write about being the brunt of Trump's attacks, over and over. Were you able to laugh it off? What was it like to be a Trump villain? Was it more fun to be villain than a hero like they say in the movies?

You know, much of the time I was able to laugh it off, and my family helped me laugh it off. In fact, I remember walking down the street in New York with my daughter, who lives in Soho. I was wearing blue jeans and a canvas jacket and sunglasses, and I was getting stopped. And I was astonished that I was getting stopped and eventually it started to get annoying to my daughter, because there's only one center of attention in our family, and it's her, not me. So finally, Lexi says, "Enough already." I said to her, "I'm just shocked that people can recognize me." She looks at me and she says, "Well, you know, Dad, it's the pencil neck." This is what you get from your own kid.

I do want to say, on a more serious note, that I found it so upsetting that he would demean his office by engaging in these kinds of juvenile taunts. It just brought the presidency down. But the more serious thing were the not-so-veiled threats he would make, calling me a traitor and saying, "Well, we used to have a way of dealing with traitors." At one point he met with, I think, the president of Guatemala and said, "Well, you know, you used to have a way in your country of dealing with people like Adam Schiff." Something along those lines. And, you know, that reaches people that are not well. I get death threats, and that part, you really couldn't laugh off.

In the book, you write that after Jan. 6 there was no need for impeachment hearings before the vote: "No investigation would be necessary given we were all witnesses to his crimes," speaking of Trump. When you think back on that now, do you think the Department of Justice should be doing more in terms of criminal prosecution of Donald Trump and the people around him?

I do think the Justice Department should be doing a lot more than what I can see — which is, with respect to some things, nothing at all. What I would point to most specifically is Donald Trump on the phone with the secretary of state of Georgia, Brad Raffensperger, essentially trying to browbeat him into finding 11,780 votes that don't exist. I think if you or I were on that call, or any of my constituents, they would have been indicted by now. I understand the reluctance on the part of the attorney general to look backward, but you can't have a situation where a president cannot be prosecuted and when they leave office they still can't be prosecuted — that they're too big to jail, somehow.

I think that any criminal activity that Donald Trump was engaged in needs to be investigated. It may be ultimately that the attorney general makes the decision after investigating that for what he thinks is the country's best interests it makes sense not to go forward with a particular charge. But I don't think you can ignore the activity and pretend it didn't happen.

Last week we had the vote in the House on charges of criminal contempt against Steve Bannon. Then it goes to the Justice Department. Do you have any sense what they will do? If they choose not to indict Bannon or to prosecute him, would you be calling for changes in the DOJ?

Well, first of all, I think they are going to move forward. That's my personal opinion. It's my hope and expectation. I say that because of a couple of things. They have repeatedly made it clear now, as they did to Mr. Bannon but in other contexts as wel,l that they are not asserting executive privilege, that the public interest here far outweighs any claim of privilege. So Steve Bannon had no basis in which to simply refuse to appear. I also think that because the Justice Department itself has not resisted our efforts to interview high-ranking, former Justice Department individuals, they understand the importance of this. Should he not go prosecuted, it will essentially send a message that the rule of law doesn't apply to certain people close to the former president. And I just cannot imagine that's a message that the Justice Department wants to send.

Rolling Stone recently reported about certain members of the House, including perhaps Rep. Paul Gosar [of Arizona], meeting with some of the Jan. 6 organizers. It's not completely clear because it's coming from anonymous sources, but there was an allegation that Gosar promised blanket pardons to people through Donald Trump. I know you're on the Jan. 6 committee. Will you be investigating that?

Yes, we will be investigating these issues to see whether the public reports are accurate or not accurate, what role members of Congress played or didn't play. We are determined to be exhaustive. Nobody gets a pass, so yes, we will be looking into all these things. Look, you can't dismiss those allegations as being too incredible to be true because Donald Trump was dangling pardons to people like Paul Manafort. He was attacking those who did cooperate, like Michael Cohen, calling him a rat. The idea that they would dangle more pardons cannot be excluded. And if members of Congress played a role in that, then the public has a right to know. Ultimately Congress and the Justice Department will have to figure out what the consequences need to be.

There was reporting in the Washington Post on the Willard Hotel war room with things I had never seen, including the claim that in early January, after all the appeals were done, recounts had been done, the Electoral College had voted and we were days away from the electoral vote count, Trump was on the phone with over 300 state legislative officials in battleground states, telling them essentially to decertify the results. Could that potentially rise to a crime?

That ultimately would be a decision the Justice Department would have to make, whether it violated specific statutes and whether they could meet their burden of proof. But what we are most focused on is this violent attack on the Capitol, just the last stage in an effort to bring about a coup. When all the litigation failed, when all the efforts to coerce the vice president failed, when the efforts to get Brad Raffensperger to find votes that didn't exist failed, then that was the plan: Use violence to intimidate the vice president or the Congress into not doing their job, to interrupt that peaceful transfer of power. Was that the plan all along? What role did the president play, and people around him?

I think the biggest black box in terms of unknowns, is what the president's role was in all this. We know he incited the insurrection, and that was sufficient grounds to impeach and remove him. But what role did he play? How much was he aware of the propensity for violence, the participation of white nationalists? How much was he celebrating as he opened those doors and windows and heard the sound of the crowd the night before, saying they would use violence if necessary to make sure that he stayed in the office?

You're a former prosecutor. If Donald Trump is not punished some way criminally for his actions, what would stop Trump or another president from mimicking the same conduct, thinking you can get away with this? This was a two-pronged coup attempt, one behind the scenes and one right in our face on Jan. 6. How could this be permissible in the United States of America?

It's a very good question, and I think you can draw a straight line between Trump's Russia misconduct, in which he invited a foreign power to help them cheat in an election and then lied to cover it up — and feeling he had gotten away with that after Bob Mueller testified — and that leading the very next day to his Ukrainian misconduct and new and different ways to try to cheat in the next election. When he got acquitted and escaped accountability for that in the first trial, you can draw a straight line to the insurrection and even worse ways to help to try to cheat in the election.

If he were to ever take office again, where does that straight line continued to go? So, yes, I think the danger is real and what's going on around the country right now, in which the Republicans are running with the Big Lie to strip independent elections officials of their duties and give them over to partisans, seems to be the lesson they learned from the failed insurrection — which is that next time, if they couldn't find a secretary of state in Georgia to come up with votes that don't exist, they'll be sure they have someone there who will. That's why I titled the book "How Close We Came to Losing Our Democracy and Still Could." Because the danger that we still could is all too real.

In the book, you quote from Shakespeare's "Twelfth Night," talking about what we saw and went through with Donald Trump. If this were a play, I could condemn it as an improbable fiction, but unfortunately it was real, we lived through this. At this point I'm thinking of "Hamlet" and our democracy: To be, or not to be. It really seems that's where we are, that it's that dire. Do you get a sense that enough Democrats, enough people in the media, share that dire view of the trajectory of our nation? Where just because this republic has been here for 240-plus years doesn't mean it will be here for eternity, and that something needs to be done to save it?

I don't think people feel a sufficient sense of alarm. It's one of the main motivations for me to write this book. I got together recently with a couple of friends of mine. They're a husband and wife married for decades. They're in their mid 90s. And I asked them, "Have you ever seen anything like the present?" And they told me, "Look, we remember World War II, the Great Depression. We remember Korea and Vietnam, the civil rights struggles, the Cuban missile crisis. We've never been more worried about the future of our country and democracy than we are today. Because during all those former crises, we always knew we would survive as a democracy. But right now we just don't know." People do need to feel that sense of urgency — not a despondent state, not despair. We don't have the luxury of despair. It needs to motivate us to be active.

I paint a portrait of a lot of the heroes that came through this period of time, Marie Yovanovitch and Fiona Hill and others. We need to use them to inspire us to act. We can't all be Marie Yovanovitch, but in our own way we can figure out what we can do to come to the rescue of our democracy in this dark hour.

Shares