It was late, the lights already off in my house, but the message lit up my bedroom like a full moon. It was the person I'd been waiting for — the "dealer."

"We work with a group of antivax doctors who have access to the database," the WhatsApp message read. "Your data will be updated to the system and a QR code sent which you can verify on your country's hub."

The message was the culmination of an investigation into fake COVID-19 vaccination cards. I'd read many stories about these cards, some funny, some shocking. But I wondered: just how easy is it to get them? And how common are they?

The answer to that question could have dire implications for public health. If they were that easy to acquire and pass off, that was reason to be more suspicious of strangers in public places that are supposed to be vaccinated-only, compromising a crucial pandemic safety policy.

Earlier in the day, I searched Reddit and Facebook; it took mere minutes to find a purported fake card dealer, the one with whom I later contacted on WhatsApp. At noon, I expressed interest in buying a card; at 8:50 p.m. later that night, they finally got back to me.

Three hours later, I found myself waiting for answers to questions about how this illegal operation works, as I pretended to be interested in making a purchase. To my surprise, they were talkative. I even asked for a photo of what the card would look like; in response, I was sent a photo of an example from a "satisfied client."

* * *

As vaccine mandates take hold in various states, and the implementation of a federal mandate for private-sector businesses looms, a black market for fake vaccine cards has emerged. Perhaps this comes as no surprise: as this reporter observed first hand, they're easy to seek out, and the cards themselves are printed on simple cardstock. Perhaps more surprising is the cost: some go for hundreds of dollars — meaning that some consumers are so passionate about avoiding a free vaccination that they are willing to shell out for something they could have gotten at no charge had they been willing to be inoculated.

According to the cybersecurity firm Check Point Research, the number of sellers offering fake vaccination cards increased on social media platforms and the dark web after President Joe Biden announced a plan that would require private-sector workers to be vaccinated against COVID-19 or be regularly tested for the coronavirus. Prior to the announcement, Telegram groups selling forged vaccine cards had as many as 30,000 subscribers, after the announcement some groups saw an uptick to nearly 300,000 subscribers.

"The market on Telegram for fake vaccination cards has been exponentially growing, and the price for a fake card has doubled, and that kind of big exponential growth time-wise really syncs up with when the federal mandate for vaccinations was released," Maya Levine, a cybersecurity expert at Check Point Research, told me. "And since that announcement, we estimate that the number of sellers on this black market have gone up by about 10 times."

For the unfamiliar, Telegram is a messaging application — similar to WhatsApp — with robust privacy and secure chat and texting features, which in this case seem to attract black market vaccine card sellers.

But fake vaccine card sales aren't just happening on privacy-forwards Telegram; they're also happening on Facebook-owned WhatsApp and Instagram, according to a separate investigation by the Digital Citizens Alliance (Digital Citizens) and Coalition for a Safer Web (CSW).

"What's interesting is these nefarious actors have evolved, as the fear has evolved," said Eric Feinberg, a lead researcher for the Coalition for a Safer Web, in an interview. "And this is kind of the failure of social media to keep up with it as the fear evolves, and so has the use of these nefarious actors to use these platforms in this way."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

In the case of the purported "dealer" with whom I had been chatting, some of their claims were alarming — particularly the one about working with "antivax doctors" who could supposedly forge vaccination records digitally as well.

Are these sellers really in cahoots with doctors? It was certainly within the realm of possibility. There have been reports of health care workers with access to blank vaccine cards who went on to sell them — like one Chicago pharmacist who was charged with stealing official COVID-19 vaccination cards and selling them on eBay.

"There are cases where the source of these fake cards are not even 'fake,' because they work in a pharmacy — they have access to them and they just take them," Levine said. "Unfortunately, some people in the medical system are taking advantage of this."

NPR reported on another similar case, where a New Jersey woman calling herself the AntiVaxMomma on Instagram sold several hundred fake COVID-19 vaccination cards at $200. For another $250, a co-conspirator would then enter a fake card buyer's name into a New York state vaccination database. At least ten names were entered into the database via a co-conspirator who worked at a medical clinic in Patchogue, New York. The woman was charged with offering a false instrument, criminal possession of a forged instrument, and conspiracy.

Obviously, copying and selling COVID-19 vaccine cards is illegal — which is why they're not for sale on any reputable site on the internet.

"It is a felony to impersonate an official document, which is what a vaccination card is from the CDC is," Levine said. "It's a crime to definitely sell it, and it's a crime to try to use that fake card in places that are asking for it as proof of vaccination."

According to a warning from the FBI, anyone who sells, buys, or sells a fake vaccine card could be fined or face prison time.

"The creation, purchase, or sale of vaccine cards by individuals is illegal and endangers public safety," the warning stated. "The unauthorized use of an official government agency's seal on such cards is a crime that may be punishable under Title 18, United States Code, Section 1017, and other federal laws. Penalties may include hefty fines and prison time."

* * *

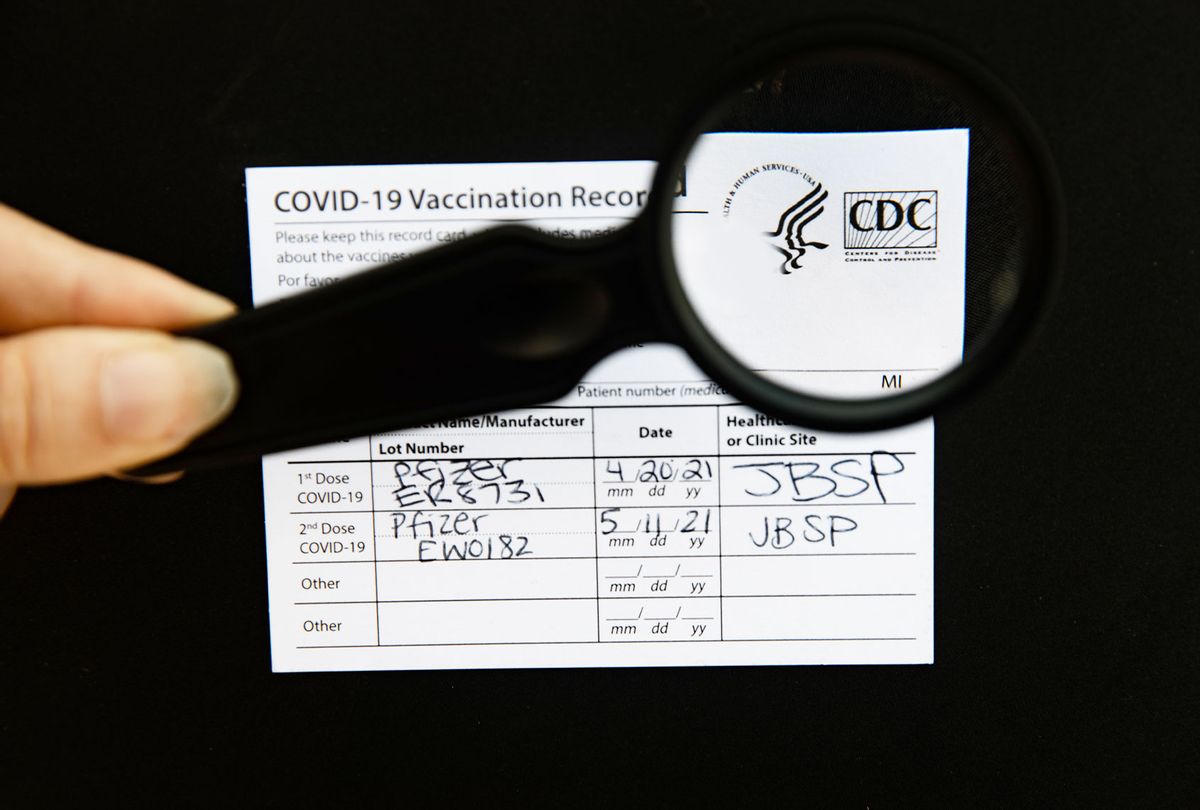

As for me, my conversation stopped with the anonymous seller after I received the photo. (Of course, I didn't intend to go through with the purchase; I'd already been vaccinated anyway, and was going through the process for the sake of journalism). The image showed a hand holding up a vaccine card that looked just as normal as my real card; the person's hand was hovering in front of a laptop screen in what looked like an elementary school classroom. There was a blackboard and a map of the United States in the background. Personal information on the card had been obscured by the sender.

I ran the photo through a reverse image search, and couldn't find anywhere else that it had been posted online. In checking the photo's metadata, I noticed that all identifying information — such as the device on which the photo had been taken or the GPS location — had been scrubbed or unrecorded.

As for how this person's operation works, much of that remains unclear. It certainly would have been revealing to see what would have happened if I'd gone through with the purchase, though that was out of the picture given its illegality.

On the forum where I found this seller, other users attested to their products' quality. And the illicit vaccine card dealer's narrative is similar to what others have found in investigations into fake vaccine cards: in general, the potential buyer is asked to pay money, told their information will be entered into a database, and asked for similar information about themselves.

There have been reports of the FBI and Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General cracking down on this operation. Last month, the National Hockey League (NHL) suspended San Jose Sharks forward Evander Kane for allegedly submitting a fake vaccine card. In Pennsylvania, two police officers were fired for the same offense.

But that doesn't appear to be making a dent on the growing industry.

Notably, purchasing a card can put the buyer at a higher risk of being scammed, or having their information stolen or sold.

"Besides the fact that it's illegal, there's a risk when you choose to give an anonymous seller your information," Levine said. "There's a very high chance that whatever information you give them, whether it be credit card information to pay for it, or your personal information, like your name and your birthday and your email, they can then take that and just as easily sell it on the dark web."

And of course, by using such a card and misrepresenting yourself, you put yourself and others at risk of contracting COVID-19.

Experts say that social media platforms also need to be held accountable, and an easy and immediate solution would be for social media platforms to share information about nefarious actors with each other. Sellers often move around from platform to platform; as I observed, a seller advertised on Facebook and then requested we move our conversation to WhatsApp.

"I think information-sharing between the platforms could be one thing that could pretty quickly make a dent in some of this kind of activity, even before Congress puts pen to paper on any legislation," said Adam Benson, from the Digital Citizens Alliance.

Shares