Just as God handed down the ten commandments to Moses at Mt. Sinai, astronomers are having their ten commandments moment this week — in the form of a much-anticipated 614-page report, handed down from a committee assembled by the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

That report — called the Decadal Survey on Astronomy and Astrophysics 2020 (informally, Astro2020) — determines the top three priorities in the field of astronomy for the next ten years. The once-in-a-decade visionary blueprint will shape the future of astronomy research, and perhaps even the trajectory of human civilization given the potential for astronomers to soon discover life on other worlds.

Indeed, while the report is chock full of proposals, one prominent one stands out: confirming that life exists on an Earth-like planet beyond our solar system.

The proposal calls for a massive space-based observatory to be launched in the mid-2040s as the first of three "priority scientific areas" regarding where investments in astronomy should be made within the next decade. The second priority is to further investigate the nature of black holes and neutron stars, and the third is to improve our understanding of the early universe.

Previous decadal surveys have included monumental endorsements that led to breakthrough scientific projects like NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, which was a top priority in a survey in the 1970s. The priorities are determined after surveying professionals in the field, which is then organized by a 20-person panel.

Nikole Lewis, assistant professor of astronomy and deputy director of the Carl Sagan Institute who contributed to the report, told Salon the process for determining the top priorities was all about what would "push the field forward."

"We're really asking ourselves 'What's really hard to do?' and 'What would be transformational?'" Lewis said. "And so exoplanets and searching for life on other worlds is really both hard and transformational, so that is a good focus area for the future of astronomy."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

This hypothetical space observatory would essentially be a more advanced version of a collection of telescopes similar to the Hubble Space Telescope, but its main priority would be to search for biosignatures on the 25 habitable zone exoplanets that have been deemed "Earth-like." The process of creating and launching such an observatory is explained in great detail in the report.

First, the report recommends that NASA establishes a new Great Observatories Mission and Technology Maturation program, which would essentially change the way major projects are developed. This newly structured program would provide an opportunity for the field to make early investments in the development of smaller versions of bigger projects to make sure they are feasible before they become too large and costly.

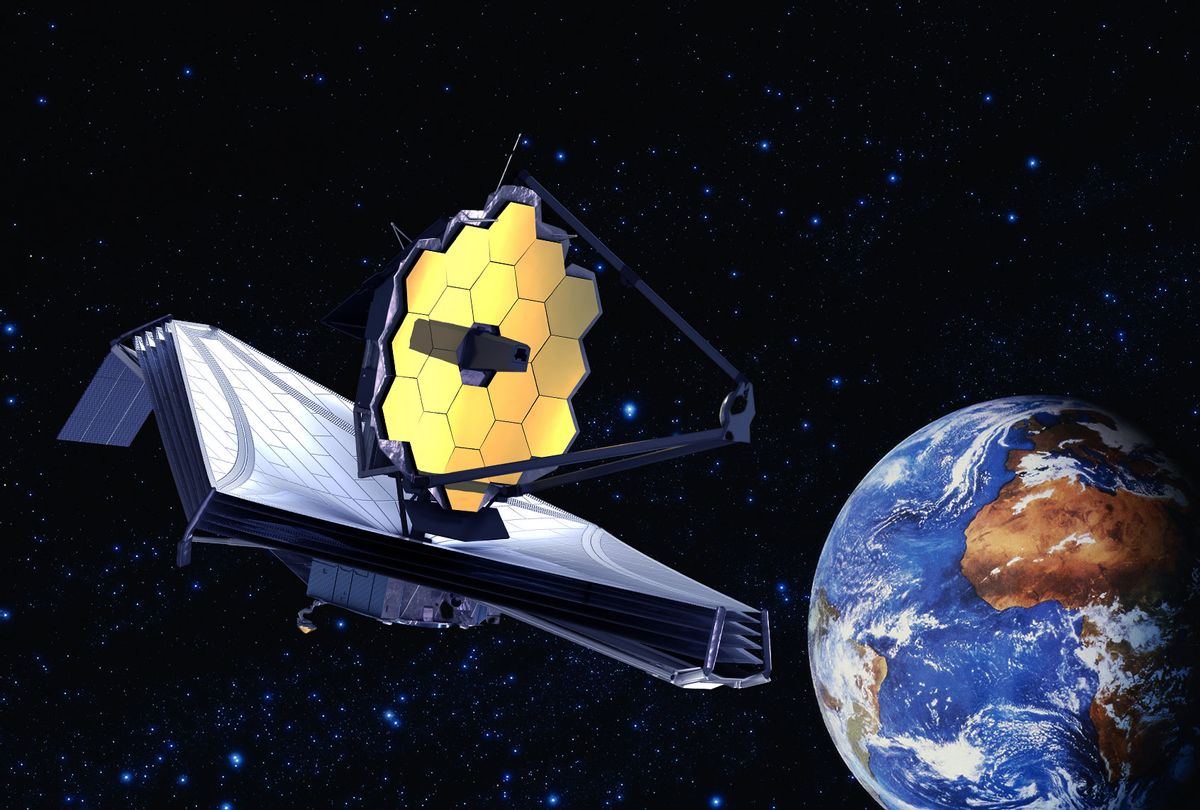

After the program has been established, the first mission would be developing an infrared, optical and ultraviolet telescope significantly larger than the Hubble Space Telescope. Scientists would build this telescope to observe planets 10 billion times fainter than their star, which is key to identifying signs of life on exoplanets in their star system's habitable zones. Lewis explained the main difference between the proposed space observatory and the James Webb Telescope — which is planned to replace the Hubble Space Telescope in December 2021 — boils down to the technology used to observe the fainter planets and provide spectroscopic data to scientists.

"In order to access planets that are in Earth-like orbits around sun-like stars, so at the same distance from the same type of star, we need a different technology," Lewis said. "You need some way to block out the starlight in order to see the relatively faint planet next to it, and so that's a lot of what's driving this technology development towards this flagship mission."

Lewis added that while the James Webb Space Telescope is going to study exoplanets, it will only be able to look at exoplanets that are very close to their stars, due to its physical constraints.

"These are typically planets that are much closer to their stars than say Mercury is to the sun," Lewis said. Yet a close-orbiting planet does not necessarily imply a barren hellscape, like Mercury; some stars are far cooler than ours, and thus even a close-orbiting planet can be habitable. In other words, the James Webb Telescope might still image habitable worlds, but not habitable worlds anything like Earth.

"The Webb telescope will really only be able to look at those types of planets that are really not around sun-like stars in Earth-like orbits, but we're going to learn a huge amount about those potentially habitable worlds," Lewis added.

Hence, while the James Webb Telescope will aid our current understanding of exoplanets, it will in some ways be limiting. However, the next proposed generation of telescopes would be able to identify biosignatures on these Earth-like planets in other star systems.

If this space observatory were able to launch in the mid-2040s, with an estimated cost of $11 billion, does that mean we would finally be able to know if there is extraterrestrial life in the universe? The short answer is yes.

"It's an exciting time because in searching for life we're going to actually discover a whole bunch of really interesting things about how planets work, and as we get to the point where we think, 'Okay, this planet we think really has life,' and we start to build a statistical sample," Lewis said. "It's really going to put in context how unique Earth is, which is important for us as humans, right?"

"Are there a bunch of Earth twins out there? Or maybe those planets that don't look like us also harbor life, and so it will be a mind-expanding moment in contextualizing our place in the universe, our uniqueness, and also our potential to think about how life might have formed outside of the context of Earth and around another star."

Lewis said the proposed plan puts astronomers and scientists in a position to have answers to these questions in our lifetime. Indeed, astronomers whose careers have been dedicated to search for extraterrestrial and microbial life in the universe are excited about this proposal.

Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), told Salon he's "excited," but is managing his expectations.

"If this new observatory or even James Webb finds a planet that has oxygen in its atmosphere, we'll think 'oh, photosynthesis, the aliens have salads to eat.' Okay, that's interesting, but keep in mind that the Earth has oxygen in its atmosphere for about 2 billion years," Shostak said. "And not too many humans were walking around with the radio transmitters 2 billion years ago, 1 billion years ago, or even 100 years ago. So it doesn't necessarily improve your immediate chances, but what it does is it gives you a reason to keep looking at this category of objects."

Shostak said it is invigorating to be so close to having answers about extraterrestrial microbial or intelligent life.

"It's fortunate to think that we might be alive when it happens," Shostak said.

Shares