As the nation slowly recuperates from the brunt of the pandemic, American workers — many of whom were lauded as “essential” only months ago — are making it clearer than ever that enough is enough.

Last year, as the U.S. economy wrestled with an unprecedented supply shortage that saw panicked masses hoarding toilet paper, millions of workers who were previously left out of national conversation were suddenly christened as “essential” to the nation. Workers in healthcare, food service, agriculture, and transportation were asked by their employers to continue performing vital services, putting both their physical and mental health on the line. Though their role in buoying the economy was undoubtedly essential, their sacrifices in many cases went unacknowledged beyond symbolic gestures.

For instance, employers routinely denied essential workers raises that took into account the added risks of working in close contact with one another. Managers also flouted common sense public health guidelines and failed to provide paid sick leave as the virus ran rampant. Even now, after nearly two years of the pandemic, only a handful of states have committed to using funds from the American Rescue Plan to lift essential workers out of financial straits.

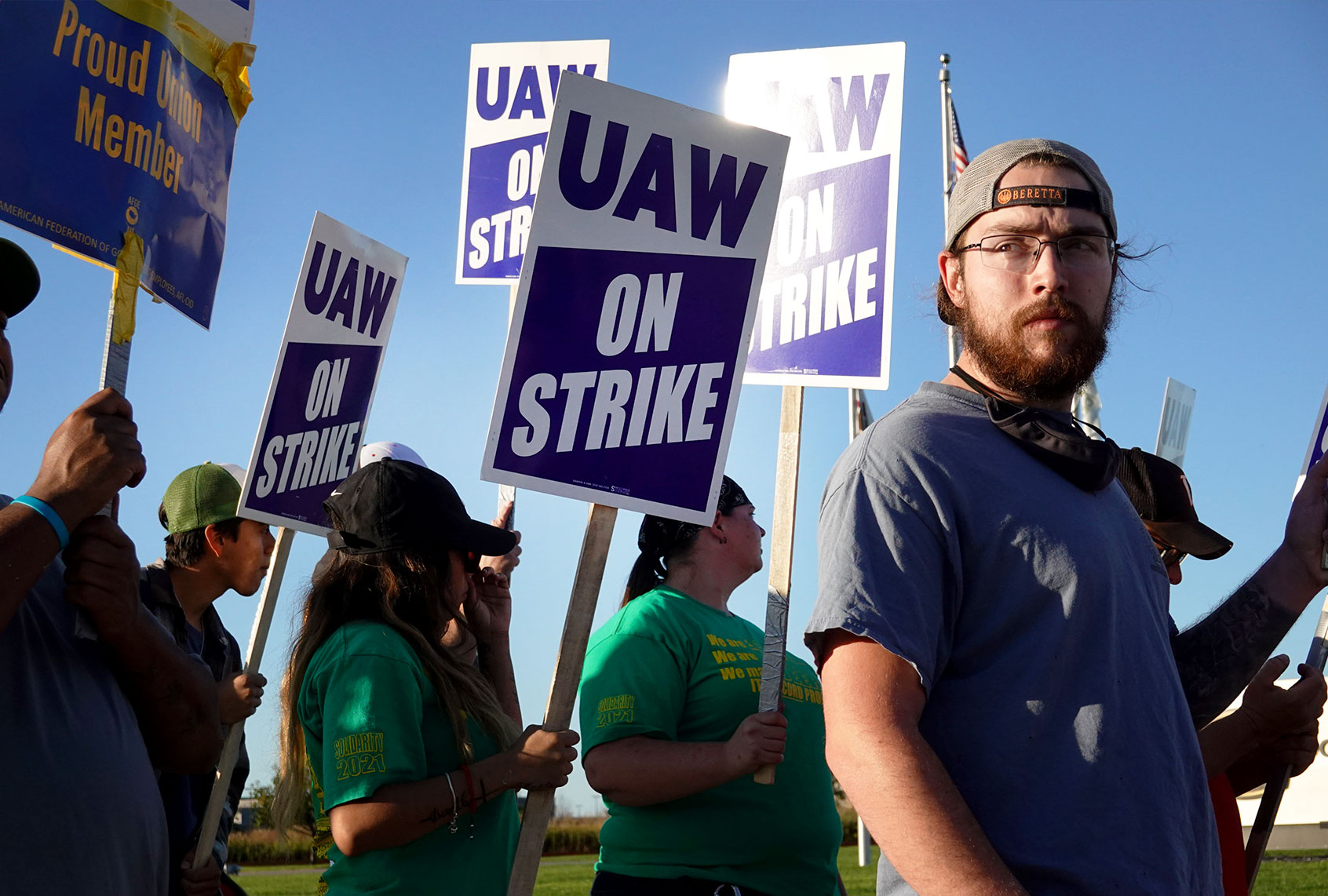

Since October, thousands of workers spanning multiple industries nationwide have been leading strikes for better pay and improved working conditions. They dubbed their national movement “Striketober.” Among their employers are agricultural machinery company John Deere, along with food producers Frito-Lay, Kelogg, and Nabisco. Major work stoppages have also been organized by healthcare workers at hospitals, graduate students at Harvard and Columbia, and the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE), which represents roughly 150,000 artisans, technicians, and craftspersons in the film and television industry.

RELATED: ‘Striketober’ in full swing as nearly 100,000 workers authorize work stoppages across U.S.

Corrina A. Christensen, Director of Public Relations & Communications of the BCTGM International Union, which represents workers at Frito-Lay, Kelogg, and Nabisco, told Salon that workers are capitalizing on a “newfound sense of leverage” as the employers reckon with the consequences of the pandemic.

“All of our strikes in 2021, beginning with Frito Lay, then Nabisco and now Kellogg, have everything to do with workers being fed up with employers bent on disrespecting their work and demanding take-aways in wages, benefits, forcing overtime…after they were upheld as ‘essential,'” Christensen wrote over email.

The unrest is something of a statistical anomaly for this year, according to an analysis conducted by the School of Industrial and Labor Relations at Cornell University, which found the number of worker strikes has skyrocketed in recent weeks. In October alone, Cornell’s Labor Action Tracker recorded 57 strikes across the nation – more than double the monthly average from January to September. The number of workers on strike in October likewise leapt to 25,000 – a far cry from the preceding three-month average of 10,000.

To be sure, the scale of demonstrations is not record-breaking against the backdrop of American labor history. For instance, during the U.S. post-war period from 1945 to 1946, when the country’s labor market was struggling to accommodate an influx of soldiers from World War II, over 5 million workers in coal mining, automobiles, and public utilities organized strikes in protest of poor pay and substandard working conditions.

That said, the timing of Striketober is unique, particularly since the labor market had already been hemorrhaging workers at record levels in the months prior.

Back in April of this year, economists observed a staggering exodus from the labor market now colloquially known as the “Great Resignation.” The Bureau of Labor Statistics found that 4 million workers left their jobs in July. In August, this number reached 4.5 million. According to a Morning Consult poll from mid-September, about 46% full-time employed adults are looking for or considering a different job. Other surveys have estimated this number could be as high as 70%. And while the phenomenon has had an outsized impact in food service, healthcare, and hospitality – all sectors in which workers are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 – it has touched virtually every American industry.

RELATED: How the business lobby created the “labor shortage” myth — and GOP used it to slash benefits

Experts have entertained a great number of explanations for the Great Resignation – namely that workers have reshuffled their priorities amid the pandemic, especially with the rise of remote work. Whatever the reason may be, it’s given workers substantially more bargaining power than they usually have in the private sector, said Joseph McCartin, Executive Director of the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor at Georgetown University.

“Previous periods following great national crises and mobilizations have been the periods that…upend the status quo and they transform people’s expectations,” McCartin told Salon in an interview. “Workers can have power that they didn’t have. The combination of the Great Resignation and the strike wave in the context of emerging from the pandemic is really crucial.”

Some economists have broadly posited that the Great Resignation is its own form of a general strike.

“People are using exit from their jobs as a source of power,” Thomas Kochan, an MIT professor of industrial relations, told The Guardian. “They’re empowered because of the labor shortage.”

Thus far, Striketober has seen differing levels of success. On Saturday, John Deere and the United Auto Workers (UAW) – a union that represents 10,100 production and maintenance strikers protesting across 12 company facilities – reached a tentative agreement that ensures increases to hourly wages and preserves the employee pension program, according to The New York Times. The deal, which was apparently the company’s last offer, proposes a 30% pay increase over six years – an improvement from an earlier proposal. However, this week, a majority of workers voted the contract down, arguing that the company could afford to extend a better offer.

“It seems general membership feels emboldened by this current political moment of labor power. They’re pushing things further than the union leadership apparently wants to go,” Victor Chen, a sociologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, told ABC News. “It’s a gamble, but the economic wind is against their backs, given widespread supply chain problems and the current worker shortage.”

Kellogg workers appear to be facing similar roadblocks in the negotiation process. Since October 4, roughly 1,400 workers from all of the company’s plants across the country have been organizing work stoppages over complaints of mandatory overtime and 84-hour workweeks, according to The Washington Post. At the crux of the conflict, however, is Kellogg’s “two-tier pay system,” reports MLive, which assigns different pay rates on the basis of workers being “legacy” or “transitional” employees. In addition to a $10 pay gap between the two groups, transitional employees are not offered pensions, paid holidays, and health care coverage, BCTGM claims. Though Kellogg in 2015 reportedly pledged to facilitate the promotion of transitional employees to legacy status, BCTGM said, the company hasn’t made good on this promise.

In Kellogg’s latest proposal, officially deemed its “Last Best Final Offer,” the company would apparently eliminate the company’s two-tier pay system, ensure wage increases for transitional workers, enhance all employee benefits, and increase all employee pensions. On Wednesday, however, BCTGM struck the offer down, suggesting that the company could bring more to the table for its workers.

“Many battles have been fought and won in the dead of winter. This is no exception. BCTGM Local 50 will hold the line for a fair and equitable contract for all of our brothers and sisters,” said the union’s president this week.

Of all the present union negotiations, IATSE’s may be closest to the finish line. On November 12, IATSE will hold a ratification vote on a new contract with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, a trade organization that bargains on behalf of employers in the entertainment industry. The contract culminates weeks of negotiations around rectifying the industry’s history of exploiting crew members, who have long struggled with unlivable wages, excessive working hours, and deficient time off, according to AP News.

After months of stalling negotiations, IATSE early last month threatened to have its workers strike if a better contract wasn’t reached. The strike was narrowly avoided on October 16, when both parties agreed on a contract that, among other provisions, ensures at least a 10-hour turnaround time between shifts and 3% wage annual wages hikes over the next three years. IASTE’s leadership has encouraged workers to accept the terms of contract, but according to Variety, union members are far from unanimous in their feelings.

Emotions within entertainment unions are running especially high in light of the Rust shooting incident, in which IATSE cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was fatally shot on set by actor and producer Alec Baldwin, who was allegedly unaware that a prop gun was loaded with live bullets. According to The Los Angeles Times, in the hours leading up to the mishap, seven Rust crew members staged a walkout from set over gun safety negligence.

“The game has changed with this accident, and it can no longer be business as usual,” David Feldman, a member of IATSE 700 (Motion Picture Editor’s Guild), told The Hollywood Reporter. “I feel a gut feeling to vote no. [IASTE’s] leadership has been stressing a yes vote, and I’m not sure that a yes vote under these circumstances is the right response.”

While Striketober has brought about a staggering level of labor unrest, it comes at a time when union participation has long been at a historic low in the U.S. According to a 2015 analysis by NPR, in 1965, roughly a third of the American workforce belonged to a union; now, that number is closer to 10%. By the Reagan Era, which ushered in a series of neoliberal policies designed to deregulate Big Business, public support for unions dropped from 71% in 1865 to around 55% in 1984, according to Gallup.

Today, 68% of the American public backs union participation – a sentiment explicitly shared by the White House. Back in December, President Biden promised to be “the most pro-union president” in American history. And during the Amazon organizing effort back in March, where warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama sought to form the company’s first union, Biden, without naming the company, said “there should be no intimidation, no coercion, no threats, no anti-union propaganda.”

RELATED: Biden just backed a union drive in Alabama but didn’t mention Amazon. Here’s why that’s a good thing

More promising, however, is the fact that a large swath of the public appears to support Striketober. According to a survey by the AFL-CIO labor federation, 87% and Democrats and 72% of Republicans back the demonstrations.

“I think it’s because the public is also frustrated,” Kate Bronfenbrenner, Director of Cornell’s Labor Education Research, told Salon in an interview. “The public is frustrated with corporate America. They don’t like the greediness that they see. They are frustrated with the economy. They see prices going up, they don’t see things changing enough in terms of COVID.”

“And so they feel the strikers,” she added, “are expressing the same frustration they are.”