In May 2018, Bari Weiss — then an editor and writer at the New York Times — published an op-ed that introduced an informal network of writers and thinkers hellbent on stamping out what they perceived as a grievous assault on America's most cherished value: freedom of speech. This group, which mostly derived from elite academic institutions, professed the supposedly courageous view that the American left — with its fetish for diversity, intersectionality and "political correctness" — had infected higher education with an authoritarian culture of censorship, suppressing unpopular views on issues like race, sex and gender. This phenomenon, they proposed, was "tearing American society apart."

That was the genesis moment, more or less, for what has become known as the "intellectual dark web." Now, after three years of spreading their contrarian gospel, several members of the IDW (along with ideological fellow travelers) have announced an ambitious effort to begin sewing the fabric of society back together. This week, Weiss formally unveiled the University of Austin (UATX), a proposed but largely still hypothetical private liberal arts college in Austin, Texas. Not to be confused with the University of Texas at Austin, one of the premier land-grant institutions in the country, UATX sets out to provide an alternative locus of learning for students seeking "the unfettered pursuit of truth."

"We are alarmed by the illiberalism and censoriousness prevalent in America's most prestigious universities and what it augurs for the country," the school's website reads. "But we know that there are enough of us who still believe in the core purpose of higher education, the pursuit of truth. That's why we are building UATX."

RELATED: Rising GOP star Ron DeSantis goes after campus thoughtcrime with vague, threatening new law

The not-quite-existent university's board of advisers includes 31 high-profile public figures, ranging from school administrators, journalists, and artists to scientists, historians, and business leaders. Founding trustees include Weiss, historian Niall Ferguson, evolutionary biologist Heather Heying, venture capitalist Joe Lonsdale and the former president of St. John's College, Pano Kanelos.

There are several points of commonality among the school's emergent leadership, but the primary through-line is that just about all of them are persona non grata in left or progressive circles, largely because of disputes over things they have said or done.

In 2018, for instance, Ferguson, a senior fellow of the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, resigned from his leadership role on a university speaker series after it was revealed that he had asked conservative students to conduct opposition research on a left-wing student activist. Five years earlier, Ferguson suggested at a conference that 20th-century economist John Maynard Keynes lacked concern for the future because he was gay and had no children. (In fact, Keynes can better be described as bisexual, and had a long and apparently happy marriage with former ballerina Lydia Lopokova — the sort of historical fact Ferguson ought to know.)

Lonsdale, a technology entrepreneur and investor who founded the Peter Thiel-backed data analytics firm Palantir Technologies, has also sparked considerable controversy. Over the past decade, Palantir has been hit with accusations of fraud, conspiracy, copyright infringement and racial discrimination. In 2017, The Intercept found that Palantir was "mission critical" to the Trump administration agenda of arresting and deporting the parents of undocumented migrant children.

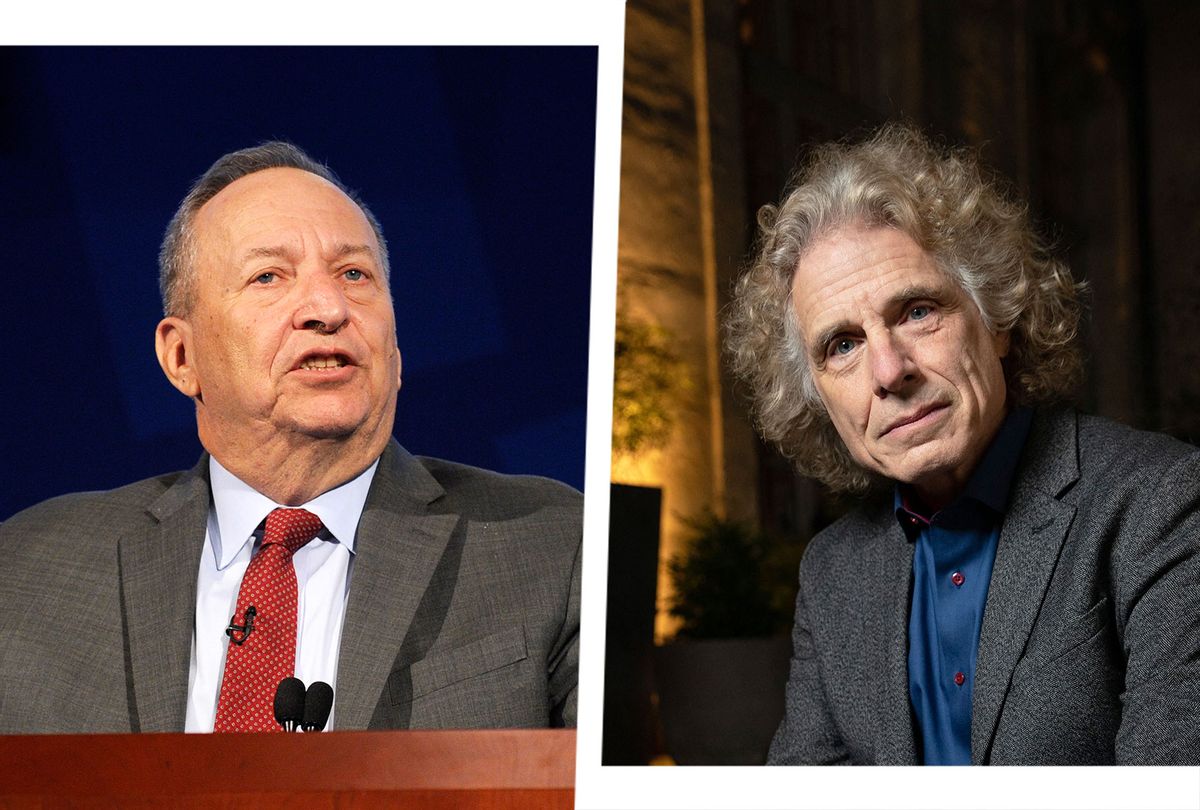

At least two members of the school's board had direct ties to the now-deceased child sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein, including economist and former Treasury secretary Larry Summers and the best-selling author and psychologist Steven Pinker. Another board member, Princeton classics scholar Joshua Katz, has been accused of engaging in inappropriate conduct with three of his past female students.

RELATED: Steven Pinker, Sam Harris and the epidemic of annoying white male intellectuals

None of this has gone unnoticed by commentators on the left, who over the course of the past week have launched a stream of satire, vitriol and more serious accusations at the newly-born institution.

What may be of greater concern, though, is the considerable ambiguity surrounding the school's legal, financial and administrative status, which has led some of its most strident critics to wonder whether UATX is more than another Trump University.

As the school's website admits, UATX is unaccredited and is currently not authorized to operate as a private post-secondary institution in the state of Texas. Accreditation can take several years, depending on the entities involved, but the UATX site suggests, without explanation, that "conversations with our accredited partners lead us to believe that we'll have a much shorter time frame than that."

Specifically, UATX is seeking accreditation from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board and the Higher Learning Commission (HLC), a regional accreditor that has been criticized twice by the Department of Education over its accreditation of for-profit colleges, including American InterContinental University and the now-defunct Art Institute of Colorado. In 2010, the department considered sanctioning the HLC, but ultimately chose not to.

Though UATX outlines no clear path toward accreditation, it has promised to offer classes in "entrepreneurship" and "leadership" to graduate students next year, with a specific program dedicated to "forbidden courses" that will promote "spirited discussion about the most provocative questions that often lead to censorship or self-censorship in many universities." UATX says it intends to roll out an undergraduate program in 2024, with the first two years focused on helping students learn "self-mastery" and the second two "mastery in their fields."

Some experts in education, law and leadership ethics are dubious that the school's ambitious academic plans can possibly jibe with its ill-defined path toward accreditation.

Joanne B. Ciulla, director of the Institute for Ethical Leadership, told Salon that UATX has offered "a very odd model."

"Anybody can teach classes — you just can't get university credit for it," Ciulla said in an interview. "So what [UATX] will have to do is say, 'You'll start taking classes, and then when we get accredited, you'll get your credits for them.' But who would want to do that? Because it's not just when we get accredited, but if we get credited."

Tristan Snell, a managing partner of MainStreet.Law, which prosecuted the case against Trump University, posted a series of tweets casting doubt on the university's legal and organizational integrity. "Is the University of Austin licensed as a school in the State of Texas? Is it allowed to call itself a university?" Snell asked. "Parallels to Trump University could be closer than you think."

Others expressed concern about UATX's apparent lack of faculty and administrative staff, aside from the school's three founding faculty fellows.

"While not accredited yet, UATX will seek accreditation and try to enroll its first master's students next fall," Daniel W. Drezner, a professor of international politics at Tufts University, wrote in The Washington Post. "And might I just say good luck to the nonexistent admissions staff that will have to gin up that process this late in the game!"

UATX has also revealed nearly nothing about its finances. According to the school's website, UATX is seeking nonprofit status, which prevents it from directly taking non-taxable donations from benefactors. Instead, the university has partnered with Cicero Research, a nonprofit incorporated last December that it's using as a fiscal sponsor.

"Cicero Research is not a funder of UATX; it is the fiscal sponsor of UATX while UATX waits for its applied tax-exempt determination from the IRS," Hillel Ofek, the school's vice president of communications, told Salon by email. "Sponsorship is a frequently used practice of a previously-approved non-profit organization offering access to its legal and tax-exempt status to another group. Joe Lonsdale is one of our leading benefactors and we are honored to have his support. We have several seven-figure donors committed and have already received over 600 donations."

In a brief email to Salon, Lonsdale attempted to assuage concerns about UATX's financing, saying that "there are several hundred funders at this point and a lot of major donors have stepped up alongside me both before this announcement and more after already." He declined to comment further.

But according to a Cicero filing from December, the nonprofit reported zero financial assets and no full-time employees. It appears to operated from a residential address in Austin owned by Jen Dirmeyer, who told Salon through a message on LinkedIn that she "left [her] position as Head of Operations for Cicero in May of 2021 and [has] not had anything to do with the legal or financial structuring of the university."

For that matter, the physical address for UATX listed on its website appears to be a small office building near the University of Texas campus that is home to the law firm RashChapman, which specializes in oil and gas litigation, according to journalist Eoin Higgins. The website says that the school is "in the process of securing land," and intends to have a physical campus at some point.

Though Cicero's filings reveal virtually nothing about its finances, the entity's reported leadership includes Lonsdale and his wife Tayler, along with Clay Spence, who is described as "Philosopher-in-Residence" at 8VC, Lonsdale's current venture capital firm. Spence is also a board director at Cicero Institute, a political organization (also run by Lonsdale) that published a white paper last year advocating for a "performance-based funding formula that allocates state public higher education funding based on the post-graduation earnings of an institution's students." Spence did not return Salon's request for comment.

Cicero's description of its mission and services includes a pledge to "create and distribute non-partisan documents recommending free-market based solutions to public policy issues."

UATX, however, says it is "committed" to "freedom of inquiry, freedom of conscience, and civil discourse" and intends to remain "fiercely independent — financially, intellectually, and politically." Asked whether that mission conflicts with the apparent free-market or libertarian orientation of Cicero, neither Lonsdale nor Ofek responded.

While the apparent birth of UATX may appear sudden, it's just one of the many conservative attempts in recent history to break free from the perceived constraints of liberal academia.

"For a full century, conservative activists of different stripes — religious, free enterprise, anti-cancel culture — have dreamed big, hoping to build dramatically different institutions to salvage what they perceive as 'truth' and proper teaching," wrote historian Adam Laats in Slate.

In the 1920s, evangelical Christians like T.T. Shields and Bob Jones Sr. attempted to build a new system of "conservative scholarship" at schools like Bob Jones College and Des Moines University. More recently, Republican operatives, religious leaders and wealthy conservative donors have bankrolled such schools as George Mason University and Liberty University.

RELATED: Scandal at Liberty University: How a Christian college dismisses students' reports of sexual assault

Of course it's conceivable that UATX will break new ground and revolutionize the academic space. But running a successful college, as Laats writes, takes more than impressive names and grand ambitions: "Big dreams of school founders have been punctured by not-so-big details ... Without accreditation, classes, or degree options, all of which the founders say are forthcoming, the answer may be no. It takes more than accusing mainstream colleges of being 'broken' to create something that will actually work."

Shares