Republicans have an obvious race problem — one they prefer not to admit, even to themselves. The party’s voter base is overwhelmingly white, and Republicans are now actively trying to suppress Black voters (and other voters of color) through a range of Jim Crow tactics. They reflexively support police even in the most egregious cases of racist violence (such as the murder of George Floyd last year) and have consistently depicted Black Lives Matter as a subversive, anti-American movement. But they can’t win elections without moderate and independent voters who are uncomfortable with overt and blatant manifestations of racism, so they claim that Democrats and liberals are the “real racists.”

It seems that everyone on the right, from crackpot filmmaker Dinesh D’Souza to The Federalist, enjoys pointing out that the Democratic Party used to be the main political vehicle for white supremacy in the United States. They assume their readers will pretend not to notice that decades ago Democrats and Republicans “switched sides” (at least on the issue of race), since that would cancel out this attempted “gotcha.” In fact, the Democratic and Republican parties did not assume their current identities as “liberal” and “conservative,” respectively — and as we understand those terms today — until partway through the 20th century, and neither party stands for what it once did, especially but not exclusively on racial issues.

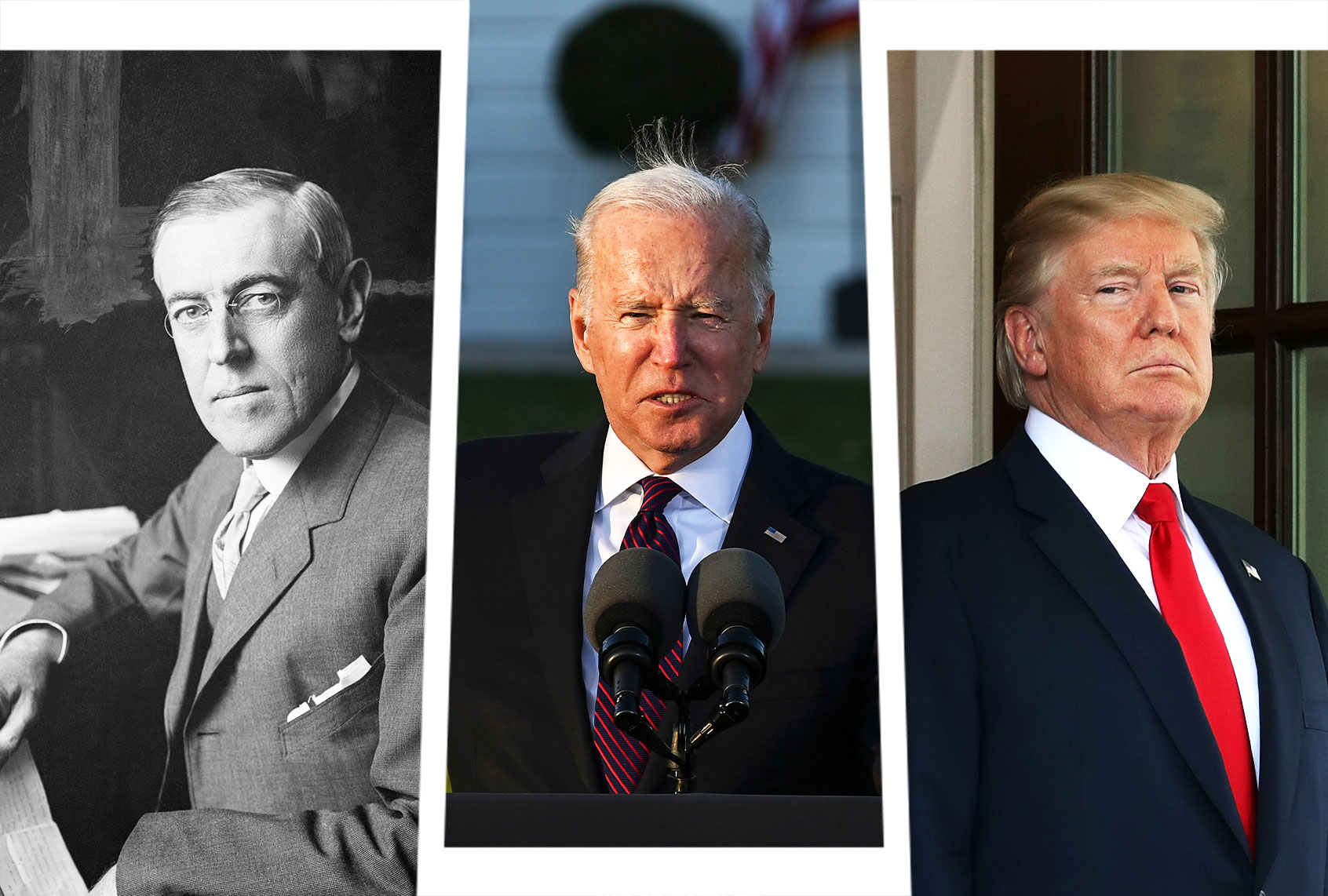

Three presidential elections play key roles in this story: Those of 1912, 1932 and 1964.

RELATED: Democrats and the dark road ahead: There’s hope — if we look past 2022 (and maybe 2024 too)

The modern two-party system began to take shape in the 1850s, with the demise of the Whig Party and the birth of the Republicans (from the anti-slavery faction of the Whigs, more or less). But in the decades after the Civil War, neither party much resembled its latter-day version. As the party of Abraham Lincoln, Republicans theoretically supported citizenship rights for Black people (at least up to a point), along with other vaguely “liberal” policies like a more centralized approach to economic policymaking, expanding the post-Civil War veteran pension system to create what some scholars argue was an early welfare state, and lavishing government support on America’s burgeoning industries. Democrats like Grover Cleveland — the only Democratic president of the later 19th century, and something of a libertarian by modern standards — thought those ideas were wasteful and dangerous.

But the Democrats of the time, incoherent heirs to the populist tradition of Andrew Jackson, were a chaotic mixture of ingredients: Big-city political bosses and urban white immigrants, agrarian populists like William Jennings Bryan (some of whose proposals would be “liberal” or even radical today), Jeffersonian idealists who preached bromides about limited government, business interests who favored lower tariffs and opposed protectionism, and Southern white supremacists, who often supported progressive economic policies alongside vicious Jim Crow segregation. Essentially, the Democrats were a motley crew consisting of everyone who wasn’t a Republican — a situation that is perhaps oddly echoed today, albeit without as many jarring philosophical contradictions.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Then came the 1912 election. Republican President William Howard Taft ran for re-election but was challenged by former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt, who believed the GOP had veered too far right on economic, environmental and good government issues. Roosevelt lost the nomination struggle to Taft, but ran anyway as candidate of the newly-invented Progressive Party — and won the highest percentage of the popular vote of any third-party candidate in American history. In fact, he got more votes than Taft, and carried six states — but both of them were overwhelmed by Democrat Woodrow Wilson. In the process Americans suddenly became aware of the Republican Party’s ideological schism, and over time self-described “progressives” would feel increasingly unwelcome in the GOP.

With Democrats back in power after many decades in the wilderness, Wilson realized he had to deal with his own party’s progressive and reactionary wings. He pushed for antitrust legislation and labor rights, lowered tariffs, and later tried to launch the League of Nations, a precursor to the UN. The native Virginian also expanded Jim Crow policies (and turned a blind eye to racist violence in the South) and clamped down on the free speech rights of socialists and other dissident groups. Wilson identified with the progressive movement when that was politically convenient, but he was also a white Southerner deeply invested in the “Lost Cause” mythology of the Confederacy. While there are other contenders for this prize, Wilson may have been America’s most overtly racist president; his attitudes seemed extreme even to other white Americans at the time. He proved to be the practical embodiment of his own party’s deep internal tensions, and unsurprisingly closed his second term widely despised.

RELATED: Election guru Rachel Bitecofer: Democrats face “10-alarm fire” after Virginia debacle

But the point here is that while the Democrats were certainly still racist in 1912 and thereafter, the two parties were losing the respective identities they’d had since the Civil War. The words “liberal” and “conservative,” which were used very differently before the Wilson presidency, began to take on their modern ideological associations. But there were large numbers of liberals and conservatives — in this modern sense — within both parties, and that would take several more decades to sort out.

The big sort began in earnest 20 years later, in Franklin D. Roosevelt’s landslide victory over President Herbert Hoover, a Republican who was widely blamed (fairly or otherwise) for the stock market crash of 1929 and the trauma of the Great Depression. Roosevelt set out, quite literally, to save capitalism with his famously ambitious agenda, known as the New Deal. Politically the New Deal allowed Democrats to forge a majority coalition by becoming the party that offered economic security to America’s most vulnerable citizens, and by greatly expanding government aid and assistance in many other areas of life. The basic premise of this agenda was summed up by Roosevelt himself in his 1944 State of the Union address:

We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. “Necessitous men are not free men.” People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.

Roosevelt’s economic and political innovations laid the foundations for several decades of American prosperity that, among other things, allowed the baby-boom generation to flourish as no other generation had before (or has since). They also greatly expanded the Democratic constituency, which now included unionized workers (a much larger fraction of the population at the time), “white ethnic” immigrants, students and intellectuals — and Black people in Northern cities (which were pretty much the only places they could vote). Southern whites continued to vote for Democrats for several more decades, partly based on tradition but also because the New Deal did a tremendous amount to improve living conditions in the South. But arguably, the die was cast: Rural white supremacists, leftist intellectuals and the rapidly growing Black populations in big cities couldn’t remain in the same party forever.

RELATED: Democrats can win the culture wars — but they have to take on the fight early and often

And indeed all that changed after 1964, when Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson, who took office in the traumatic aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, began pushing through historic legislation on civil rights and voting rights — partly out of genuine conviction and partly under enormous pressure from the civil rights movement and leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. As Johnson himself clearly foresaw, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 — which established full racial equality, at least as a matter of law — drove white Southerners out of the Democratic Party, apparently forever. A conservative insurrection within the Republican Party began immediately, resulting in the nomination of Barry Goldwater (essentially a segregationist, although he was not from the South) in the 1964 election. Goldwater lost to Johnson in an epic blowout, with the Democrat receiving a higher percentage of the popular vote than any candidate before or since — but, again, that’s not the important part. Black voters and other minority groups almost unanimously supported Johnson and the Democrats, who were now officially the party of civil rights. In practical terms, and allowing for ideological outliers like Clarence Thomas and Candace Owens, Republicans have effectively been an all-white party after that election.

So in fact it’s too simplistic to say that the Republicans and Democrats “switched sides.” It was clearly a bit more complicated than that. From the pre-Civil War period through Woodrow Wilson’s administration, the Democrats really were a white supremacist party — along with a whole bunch of other more or less incompatible things. But in a gradual process that began with the arch-racist Wilson and accelerated through FDR and LBJ, the Democrats assembled what we would now call a “liberal” coalition, with support for racial equality (at least in principle) as a central pillar. Even after 1964, the transformation was not complete, and some “conservative Democrats” and “liberal Republicans” hung around into the late 20th century. (George Wallace was a Democrat, for instance, while Nelson Rockefeller was a Republican; both would absolutely switch parties if they were alive today.)

You probably knew this already, but the bottom line here is that it’s either ignorant or dishonest (and likely both) to claim that Democrats are the “real racists” based on history. There is a lot of context — especially involving milestone events like the 1912, 1932 and 1964 elections — that pretty much invalidates the claim. Maybe the real answer is that neither party is very much like it used to be. Democrats used to be a nonsensical coalition that harbored lots of white supremacists (and other groups who more or less looked the other way), so in that sense the charge contains a tiny grain of truth. But then again, Republicans used to be a bland pro-business party and not a fascistic cult of personality. They should think twice about encouraging any other political party to juxtapose the present with its own history.