One of the pleasures of writing is you often surprise yourself. Poets and fiction writers try to get out of the way to allow the work to go where it wants to go; nonfiction writers, like journalists, do due diligence with research on the stories they write. In the doing of the work, writers learn new things and often disabuse themselves of notions they've held — often for a long time — that were incomplete or just plain wrong.

I planned a little piece poking fun at the Federalist Society, the wildly successful, now four-decades-old institution for conservative and libertarian thought — which is largely responsible for the current Supreme Court, the one right now on the verge of reversing or undermining the Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion — for going by that particular name. I'll still poke fun at the society, but the project turned out to be a whole lot less simple than I imagined.

Slow-reading the "Federalist Papers"

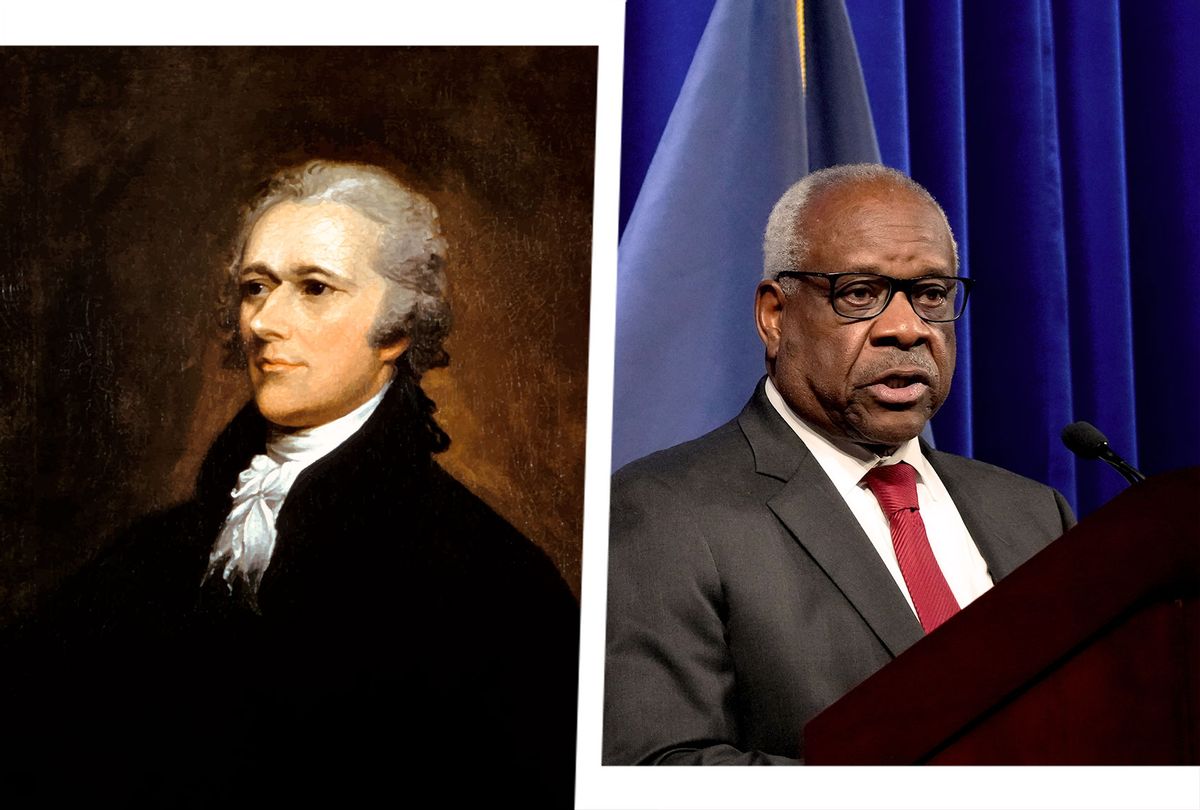

During the pandemic, I began to make my way through the Federalist Papers, the 85 essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay and published, under the pseudonym "Publius," from the fall of 1787 to the spring of the following year, urging New Yorkers to ratify the new Constitution. The Hamilton-Madison-Jay project began in response to 16 articles questioning the need for a new Constitution being published by one of the lesser founders under the pseudonym "Brutus." The pieces arguing for a strong central government were collected and published, in 1788, as "The Federalist," in the hopes that citizens of other states would be persuaded to also ratify the Constitution. The necessary nine states would ratify the Constitution by early that summer, but things didn't appear so certain when Hamilton kicked off the project, on Oct. 27, 1787, by penning his "General Introduction."

RELATED: Will Supreme Court conservatives overturn Roe? Their casual contempt for women is not a good sign

The articles — many burdened with a lumbering heading, like "The Necessity of a Government as Energetic as the One Proposed to the Preservation of the Union" (No. 23) — are often dense and make for slow reading. (For me, Hamilton's essays — he wrote or co-wrote the bulk of them — have more verve; Madison's can be, as was once politely said, soporific). The Federalist essays are still frequently described as an aid in interpreting what the founders intended in the writing of the Constitution.

But there are pithy thoughts in each essay, many of which read as if they might have been keyboarded yesterday, rather than quill-penned nearly two and a half centuries ago (like this one, from Hamilton's No. 28: "An insurrection, whatever may be its immediate cause, eventually endangers all government.") The Federalists addressed the arguments made by "Brutus," who not unreasonably worried, among other things, about the size of the proposed democratic republic, citizens not personally knowing their representatives, and a federal judiciary growing too powerful. Hamilton and Madison (Jay dropped out due to illness after writing five essays) spelled out, in detail, what the writers of the Constitution were trying to accomplish in moving the United States from a loose confederation of states to a democratic republic, a nation.

A new society ponders a name

While I was first reading the Federalist Papers (as they became known in the 20th century), I kept seeing the Federalist Society referenced in the news — almost always in the context of packing the federal and supreme courts with conservative judges with the help of Mitch McConnell — and wondered how it was that a group largely advocating against the federal government could have ever come to adopt that name.

In a fascinating 2018 article on the origins of the society, "The Weekend at Yale That Changed American Politics," Michael Kruse of Politico provides details of how some conservative and libertarian law students from Yale, Harvard and the University of Chicago, inspired by the election of Ronald Reagan, determined to work together to provide a forum on campus to welcome like-minded thinkers:

At Yale, [Steven] Calabresi and a couple of conservative law students formed a student group in the fall of 1981. Eating lunch one day, according to a subsequent telling in the journal at Harvard, they batted about possible names. The Ludwig von Mises Society? The Alexander Bickel Society? The Anti-Federalist Society? The Anti-Federalists, after all, were the ones who sought a more decentralized government at the time of the founding of the country. They landed, though, on the Federalist Society, because it invoked the "Federalist Papers" and the long-running American debate about the appropriate balance of power between the national and state governments.

The other proposed names are illuminating: Ludwig von Mises was a libertarian free-market advocate who once wrote that fascism could be a necessary temporary stopgap against socialism; Alexander Bickel, who while clerking for Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter (who himself had a storied career, one that included turning down Ruth Bader Ginsberg, in 1960, for a clerkship because of her gender) had advocated that Brown v. Board of Education be reargued and wrote extensively about the concept of judicial restraint. (Both Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito have pointed to Bickel as a major influence.)

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In Kruse's article, the naming question comes up again, this time in a letter addressed to Robert Bork from Lee Liberman, who, with David McIntosh, was helping set up a conservative law symposium at Yale, from where they were studying at the University of Chicago Law School:

Finally, our group out here settled on Federalist Society as a name, which I suppose makes up in euphony what it lacks in accuracy. If you have any brilliant ideas for a better name, however, that would be splendid.

It was a smart, instinctive move. Naming it the Federalist Society was a bit like anti–abortion rights people dubbing themselves "pro-life." It sounds good but, as Liberman noted, may lack in accuracy. It is pleasing both to the ear and to the mind because it trades on positive connotations. (Who wants their group's name to be "anti-" anything?) And the writers of "The Federalist" were capital-letter Founders of the country; to this day, apparently, no one is certain who was behind those "Brutus" anti-federalist pieces.

A bit of grift

So, as now happens more and more frequently with conservatives — indeed, this is their standard modus operandi — they chose to appropriate a term, to gloss over the truth, to create their own reality and deceive the public for all time with a nifty bit of grift. As easily as a faux patriot attaches an American flag pin to his lapel and then raises a fist of solidarity to treasonous insurrectionists, the anti-federalists simply proclaimed themselves … federalists.

Which, I hate to admit, is not exactly wrong. Federalism is indeed a political system where power is shared between a central government and smaller sub-units, like territories, provinces or states. There has indeed been a "long-running American debate about the appropriate balance of power between the national and state governments." How the term "federalism" is applied around the world depends on its historical context in a particular country.

In the context of 18th-century America, however, to be a federalist meant that you felt it was imperative to establish a stronger national government, largely to do things that the individual states could not do so well or consistently for their citizenry — mount a coherent defense, maintain a foreign policy and govern trade. Readers of Ron Chernow's biography of Alexander Hamilton may recall the accounts of Gen. Washington and his aide-de-camp, Hamilton, seeing their troops suffering in the snow without proper boots and hoping against hope that more troops and supplies would be forthcoming, as promised, from the individual states.

And yet, coming from the context of having strong, independent states under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union (its full name, which had been ratified in 1781 and had created the entity named the United States of America), some citizens were naturally suspicious of giving up any of their local control and so had to be cajoled into ratifying the Constitution. While the federalists saw strength in more collectivism, others saw such sharing as a critical loss of autonomy. Call it the masks/no masks, vaccine/anti-vax controversy of that day — all in the name of freedom, or "free-dumb," depending on your point of view.

This modest "debating society"

The election of Ronald Reagan had inspired those law students at Yale, Harvard and the University of Chicago to form the society, which continued to portray itself as a modest debating society long after it had grown and been abundantly funded and had determined to flex its muscle to remake the federal judiciary in support of conservative principles. The first advisers were archconservative law professors Robert Bork and Antonin Scalia. Right-wing funding from the John M. Olin, Bradley, Charles G. Koch and Scaife foundations poured in — reportedly $5 million by 2001. Society-sanctioned reading lists for pre-law students were drawn up, including books by the likes of Bork and Scalia and Lino Graglia, a University of Texas law professor who decried affirmative action and school integration.

It used to be that a conservative president could be surprised by the independent thinking of one of his nominees to the high court — think of Justice Harry Blackmun (nominated by Richard Nixon) or Justice John Paul Stevens (nominated by Gerald Ford) or Justice David Souter (nominated by George H.W. Bush). The Federalist Society swung into action to ensure this sort of thing would not happen again. In his 2016 campaign, erstwhile Democrat Donald Trump helped build his conservative street credibility by openly declaring that all his nominees would come from a list provided by the group — and he got that list. It was an extraordinary admission by Trump of something that normally happened behind the scenes.

We now have a Supreme Court essentially executive-produced by the Federalist Society: six of the nine justices are FEDSOC approved (and, it seems worth noting, Roman Catholics), along with hundreds of conservative judges (some not considered qualified) methodically pushed onto the federal bench during the George W. Bush and Trump years.

So what's all this effort on the part of the Federalist Society all about?

As historian Heather Cox Richardson patiently tries to remind us, the high court has been stacked with conservative ideologues to put an end to the so-called activist government that movement conservatives have decried (but often benefited from themselves) since the policies of the New Deal helped Americans climb out of the Great Depression. As she explains, this approach goes back even further. After the end of the Civil War, during the period known as Reconstruction, Southern Democrats turned to racial messaging and extolling the values of a mythical individualist, represented by the American cowboy — who, Richardson notes, was often an ex-Confederate soldier, a man who knew how to ride a horse and handle a gun. Taxation had been instituted, largely to help with the reconstruction of the South and to help destitute citizens and farmers in the former Confederate states, but some whites resented that any of their tax dollars might go to people of color, and a political formula was fashioned that would be reutilized by conservatives in a new era. As Richardson notes:

Since the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, Movement Conservatives have tapped into the idea that an activist government redistributed wealth to lazy minorities. But they have also pushed hard on the idea that true Americans are Western individualists. Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater launched this association in 1964 by dismissing Brown v. Board as governmental overreach and fictionalizing his wealthy upbringing as a hardscrabble Western frontier story; Ronald Reagan made it even more explicit by contrasting his image of the Welfare Queen with his own cowboy hat and Western ranch.

So, this dark money–funded "debating society" acts to identify and install judges who favor limiting the ability of the federal government to do much of anything: regulate business, protect the environment, protect public health and safety, provide a decent social safety net for citizens and ensure the rights of women and minorities — including the right to choose an abortion and the right to vote without intimidation and to have that vote count.

Of course, when the government works on behalf of conservative interests or comes to the rescue of a "red" state after a disaster, that's to be expected. (As Richardson points out, this hypocrisy also goes back to the years after the Civil War: The cattle industry that employed those "self-reliant" cowboys was heavily subsidized by the American taxpayer.)

Let the record show

I'll admit that my conception of federalism was somewhat lacking. Call me a victim of the Dunning-Kruger effect of knowing just enough to be dangerous. Reading the Federalist Papers, I was enthralled by the arguments of Hamilton and Madison (and Jay) and had never read about the devolution-focused so-called New Federalism that was created by movement conservatives in reaction to the expansion of federal powers created by the New Deal. I'd never even heard the political concept of devolution. Apparently, Richard Nixon had a strong hand in that New Federalism and the creation of block grants to the states to let them do as they might on social issues with minimal federal oversight, which was sold to the public as an engine of innovation.

And in some ways, that approach has worked. For example, California has led the country in establishing environmental goals, including higher gas mileage standards. These days, with Republican governors competing against each other with ever-more idiotic decrees on health policy and advocating laws to strangle voting rights of their citizens, we can all judge their peculiar style of "innovation": anti-democratic, even deadly. (The sound of devolution seems to capture our whole sad moment; not only is devolve there, one can imagine a devil dancing around it.)

Still, the record should show that the people who created the society were themselves a bit abashed at choosing to name it after the Federalist Papers. Yes, in No. 39 Madison went out of his way to calm the nerves of those who were loath to give up any political power at the state level, but he was doing so while writing strongly in favor of the adoption of a stronger central government. (It is Madison's silhouette, apparently with an altered nose — alt-nose leading to alt-facts? — that serves as the FEDSOC logo.)

So, who really cares if the right appropriated "federalism" to fight tooth and nail to limit the ability of the federal government to protect the health and rights of its less privileged citizens? Is it sour grapes on my part that this group grabbed the better name?

Sure it is.

But one must admit it is ironic that this organization, founded in part to push an "originalist" reading of the Constitution, blithely ignored the same reading of the Federalist Papers. Talk all you like about Hamilton's disquisition on judicial restraint in No. 79, the spirit of the thing, its raison d'être, was a call for a stronger central government.

Is it any leap to go from naming a states-rights group the Federalist Society to naming an anti–voting rights effort the "Honest Elections Project"?

I encourage everyone to take an originalist view of the Federalist Papers. I would also encourage people to know the history of this organization and to always, at least mentally, append "anti-" or that Nixonian "New" to any mention of it. Its founders chose, at the moment of inception, to be intellectually dishonest — which, I would further argue, is in keeping with their purposively constipated "originalist/textualist" approach.

Considering the power this "debating society" has amassed, its factory-line approach to producing lawyers and judges steeped in pro-business small-government ideology and its dark-money backing — it seems appropriate to end with a line from one of the authors of the Federalist Papers, not from those who may cherry-pick from it.

As Hamilton wrote in the concluding line of the final essay, when ratification of the new Constitution seemed almost at hand but calls for further amendment continued:

I dread the more the consequences of new attempts, because I know that powerful individuals, in this and in other States, are enemies to a general national government in every possible shape.

For the originalists and textualists out there, the emphasis was his.

More on the post-Trump Supreme Court:

Shares