Our democracy is in crisis, with many thoughtful and not-prone-to-hysteria commentators wondering out loud if the Republican embrace of Trumpism has gone so far that it may take the entire country over the edge.

A brilliant recent analysis is Thomas Edsall's article in the New York Times, "How to Tell When Your Country Is Past the Point of No Return," bookended by Barton Gellman's shocking piece in the Atlantic, "Trump's Next Coup Has Already Begun."

Both deal with the immediate crisis brought to us by the six years that Trump has dominated the American political scene and his takeover of the Republican Party.

But neither is addressing the core problem America is facing that helped bring us Trump, but goes deeper than him: money.

Specifically, money — bribery — in politics that has been legalized and expanded by reactionary "conservatives" on the Supreme Court.

But what if Congress could tell the Supreme Court it disagrees that bribery of politicians should be legal and constitutional, and takes its own steps to solve that problem?

RELATED: Supreme Court stands up for centuries of entrenched misogyny: It's a grim history lesson

The majority of Americans, for example, want their drug prices to be reasonable like they are in Canada or Europe: The reason we pay as much as 10 times more than citizens of those countries is because the Supreme Court made it legal for the big drug companies and their lobbying groups to bribe our federal politicians.

The same is true for a wide variety of issues where federal law is wildly at odds with what the public wants fixed:

- almost $2 trillion in student loan debt

- strengthening Social Security and Medicare

- banker bailouts

- health insurance ripoffs

- billions in subsidies to the fossil fuel industry

- billionaires paying 1% to 3% in income taxes (and corporations paying nothing) while average folks get soaked

- 60,000+ factories moved offshore (along with tens of millions of good-paying jobs)

- employers like Amazon and Kellogg's engaging in blatant union-busting

- internet companies tracking your every move and every keystroke, and selling that information without your permission

- climate change

Every single one of these problems continue to exist in the face of overwhelming public disapproval because one or another industry or group of right-wing billionaires has been empowered by the Supreme Court's Citizens United decision to bribe politicians.

Americans watch with their jaws on the floor as Sen. Kyrsten Sinema and the "corporate problem solvers" in the House take obscene piles of cash from Big Pharma and then refuse to vote to stop drug-price ripoffs.

There was a time in America when this was a crime called "bribery" and the overall process was called "political corruption."

In particular, after the 1970s scandals involving both President Richard Nixon and Vice President Spiro Agnew taking outright bribes, Congress put laws in place to stop elected officials from putting donor interests above those of voters and the nation.

But that was then and this is now.

Five "conservatives" on the Supreme Court gutted those laws with their 2010 Citizens United decision, over the loud objections of their four colleagues.

Democrats in Congress need to reverse that bizarre and nation-destroying decision with a new law declaring the end to this American political crime spree, and re-criminalizing the bribery of elected officials.

And they need to do it in a way that defies the court's declaration that money is "free speech" and corporations are "persons."

That defiance requires something called "court-stripping."

Republicans understand exactly what I'm talking about: They tried to do the same thing most recently in 2005 with the Marriage Protection Act, which passed the House on July 22, 2004.

That law, designed to override Supreme Court protections of LGBTQ people, contained the following court-stripping paragraph:

"No court created by Act of Congress shall have any jurisdiction, and the Supreme Court shall have no appellate jurisdiction, to hear or decide any question pertaining to the interpretation of, or the validity under the Constitution of, section 1738C or this section."

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In other words, Congress wrote that this law is consistent with the Constitution, and that they are deciding that — and the Supreme Court, with regard to the Marriage Protection Act, has no say in the matter.

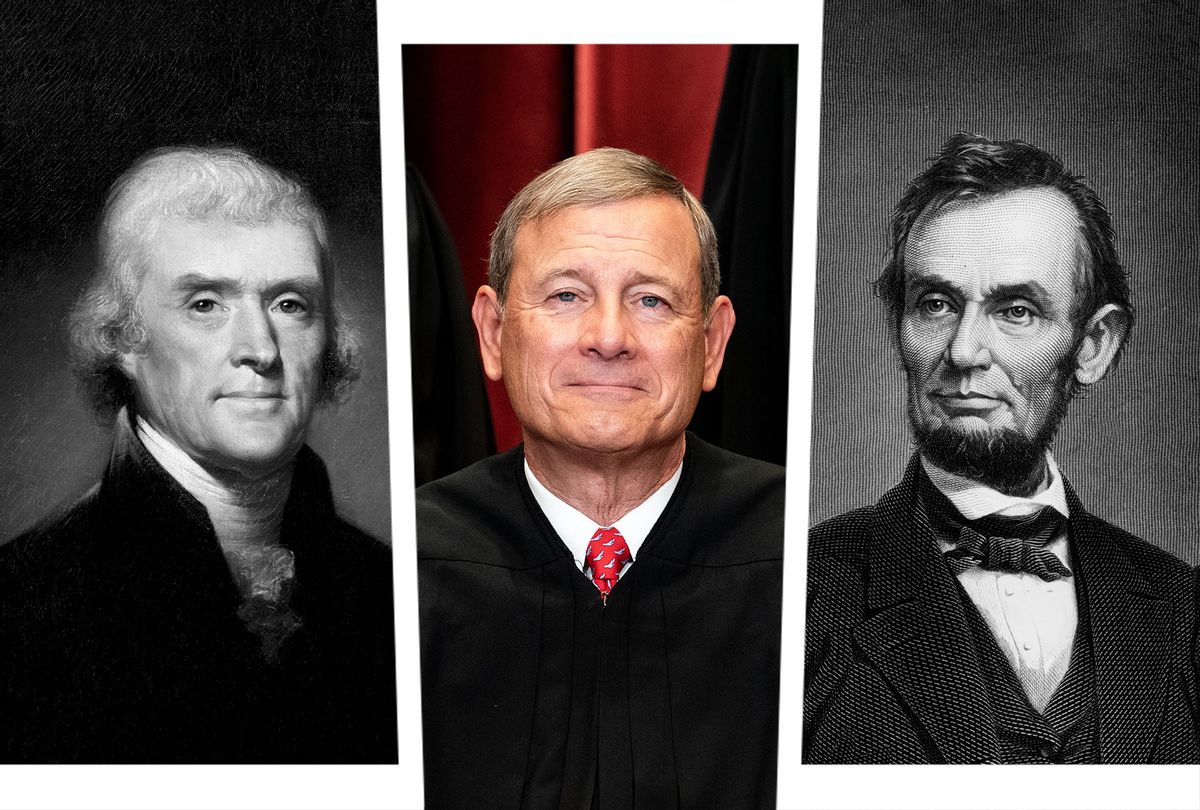

This assertion that each of the three branches should have its own opinions about a law's constitutionality is consistent with a view of the Supreme Court expressed at various times by both Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson, among numerous others of the founders.

There is literally nothing in the Constitution that gives the Supreme Court the exclusive right to decide what the Constitution says. That is a power the Supreme Court took unto itself in 1803 in a decision, Marbury v. Madison, that drove then-President Jefferson nuts. He wrote:

[O]ur Constitution … has given — according to this opinion — to one of them alone the right to prescribe rules for the government of the others; and to that one, too, which is unelected by and independent of the nation. … The Constitution, on this hypothesis, is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the Judiciary which they may twist and shape into any form they please.

Court-stripping when it came to constitutionality was how this country operated for its first 70 years, including when all the men who wrote the Constitution were alive and in government.

The Supreme Court only ruled twice between the 1789 signing of the Constitution and the 1860s on a constitutional issue, and in each case both Congress and the president at the time ignored the ruling.

The first was President Andrew Jackson, when the court ruled that the Second National Bank was constitutional and Jackson shut it down anyway, claiming it wasn't. He said:

The Congress, the Executive, and the Court must each for itself be guided by its own opinion of the Constitution. Each public officer who takes an oath to support the Constitution swears that he will support it as he understands it, and not as it is understood by others. … The opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges, and on that point the President is independent of both.

And then Abraham Lincoln chose to explicitly ignore the Supreme Court's confirmation of chattel slavery in its 1856 Dred Scott v. Sanford decision, as did Congress, and even went on to free enslaved Americans before the court could weigh in again.

In the year before his presidency, when campaigning for office, Lincoln even mocked his opponent, Stephen A. Douglas (during the first Lincoln-Douglas debate) to "Roars of Laughter" for "respecting" Judge Taney and saying he'd go along with the Dred Scott decision if elected president.

When Republicans were pushing court-stripping from the 1950s until they recently lost control of Congress, they constantly cited this long history of the practice.

The Marriage Protection Act died in the Senate, but it's one of over a hundreds of pieces of court-stripping legislation introduced — almost all by Republicans (former House GOP whip Tom DeLay was the master of this) — in the wake of the Supreme Court's decisions in Brown v. Board of Education and Roe v. Wade, and which tried to dial back the court's efforts to protect women and racial or gender minorities.

If it was worth trying for Republicans — and it drew wide public support while having a strong influence, leading the court to change its positions on issues from guns to abortion — why wouldn't it work for Democrats?

This process of "court stripping" is based in Article 3, Section 2 of the Constitution, which says:

…the supreme Court shall have appellate Jurisdiction, both as to Law and Fact, with such Exceptions, and under such Regulations as the Congress shall make.

Regulations? Exceptions?

Turns out the Constitution says that Congress can regulate the court by setting the number of its members, determining if its hearings have to be public (or televised) and whether the justices must be governed by the Judicial Code of Conduct (among other things).

And Congress can create "Exceptions" to the things the court can rule on.

It defines a process where Congress decides what is constitutional and then informs the court through legislation. In today's crisis, Congress could say, "Supreme Court, you may no longer rule on whether money in politics is 'free speech.' We're taking that power because the Constitution gives it to us and you have screwed it up so badly."

And, as it turns out, Congress has already gone there, most recently creating exceptions to what our courts may do in a law that was passed and signed by George W. Bush: The Detainee Treatment Act of 2005.

That law explicitly strips from federal courts — including the Supreme Court — most of their power to hear appeals against the government detaining, torturing, imprisoning in Guantánamo, or even killing suspected Muslim terrorists.

It says: "[N]o court, justice, or judge shall have jurisdiction to hear or consider an application for a writ of habeas corpus filed by or on behalf of an alien detained by the Department of Defense at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba…"

And that's just the beginning. There's even, as the Brennan Center notes, a court-stripping provision in the PATRIOT act of 2001.

As you can read in my book "The Hidden History of the Supreme Court and the Betrayal of America" — if you're interested in the history and John Roberts' gory details — the Supreme Court has recognized this congressional limitation on their own power virtually from the beginning of our republic.

And that's what got Ronald Reagan and the Republicans so excited in the 1980s.

If there had been enough public outrage about the Supreme Court to go along with them, they believed they could overturn both the Brown and Roe decisions, bringing back "Blacks only" schools, pools and water fountains, while putting women back in the kitchen. (As you can see, this idea can cut both ways.)

The guy who really brought court-stripping to the fore during the Reagan administration was a young lawyer named John Roberts, who compiled a huge history of case law and precedents that could be used by Congress to justify overturning Brown and Roe.

Today, he's chief justice of the Supreme Court, and his background in researching court-stripping for Reagan may be why he worried out loud — after the Texas abortion vigilante law arguments —that the court's credibility and power are now at risk like never before.

The problem, specifically, was that the Texas law is just the newest wrinkle in court-stripping. Instead of forbidding the Supreme Court from ruling on its constitutionality, the Texas abortion law simply uses its vigilante provision as a way around the court altogether.

And to add insult to injury, this time it wasn't the United States Congress that was stripping the Supreme Court or any other lower court of its power. It was a state legislature!

"If the legislatures of the several states may, at will, annul the judgments of the courts of the United States, and destroy the rights acquired under those judgments," Roberts wrote last week, "the Constitution itself becomes a solemn mockery. The nature of the federal right infringed does not matter; it is the role of the Supreme Court in our constitutional system that is at stake."

After all, the Supreme Court has no police force to enforce its edicts, no army to facilitate its decisions, nor even control over its own budget, which is in the hands of Congress. It draws its legitimacy, and thus its power, from the agreement of the other two branches and the public.

Odds are small that any legislation reimposing limits on money in politics that directly contradicts Citizens United would today become law — there are just too many bought-off politicians now, from virtually the entire GOP to a large handful of Democrats — but taking it seriously and making it high profile would stir public debate.

It might even cause the Supreme Court to reconsider Citizens United.

After all, the last time its authority and credibility was seriously challenged was by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1937, when the court threatened to declare Social Security unconstitutional. FDR threatened to replace all five justices on the who were over 70 years old — imposing instant term limits — and most of the public was with him.

He backed them down, stirred up nationwide outrage and they changed their mind (it was called "the switch [of opinion] in time that saved nine [justices]"), allowing Social Security, child labor laws, unemployment insurance and other progressive laws to go ahead, positions that hold to this day.

History shows that the court does respond to pressure, and particularly fears loss of its own power and credibility.

As Tom DeLay said back in the days of his court-stripping Marriage Protection Act: "Judges need to be intimidated" and "Congress should take no prisoners in dealing with the courts."

Putting forward such a law would highlight how Citizens United's "SCOTUS-legalized political bribery" is at the core of our political dysfunction, as right-wing oligarchs and giant corporations have taken total control of the entire Republican Party and corrupted more than a few Democrats, while polluting our public discourse with their think tanks and media outlets.

Congress needs to stand up for what's right and consistent with widely-believed American values, and legally bribed politicians isn't that. It's time to end the bribery and get something done for the people, for a change.

More on how the Supreme Court's right-wing radicals are reshaping America:

Shares