Over the last two weeks, when I scrolled through social media, I saw a theme emerge again. This time, it wasn't black squares, but a new hashtag, #StopAsianHate, attempting to make something known that I've been writing about for more than a decade. I watch an Asian American comedian with thick, straight bangs pronounce, carefully, the names of six women. I read through "Minor Feelings" and find Cathy Park Hong's words ring truer, louder: "This country insists that our racial identity is beside the point, that it has nothing to do with being bullied, or passed over for promotion, or cut off every time we talk." I send a video of a bumbling Atlanta cop to my husband.

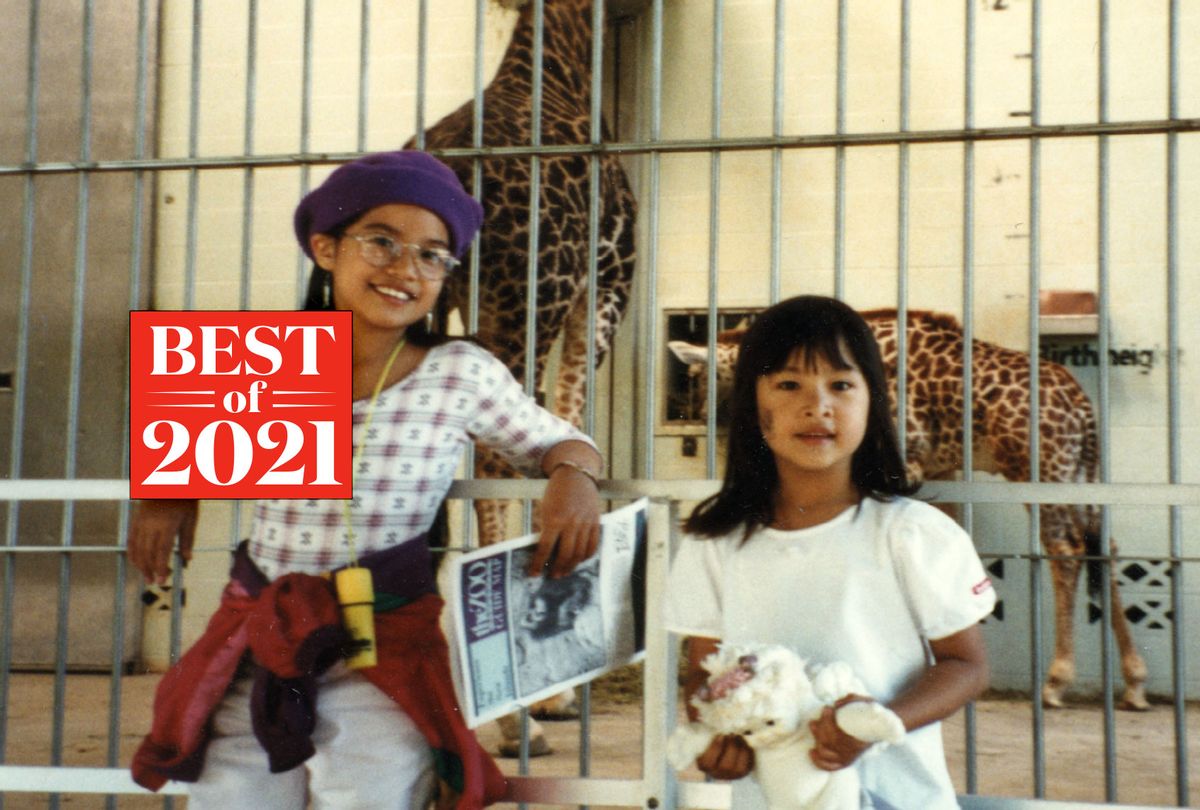

Today, I make a list of the Asian American women who raised me: my massage therapist half-Japanese mom; her older sister, my neighborhood-walking, visor-wearing Japanese auntie; and my octogenarian Filipina paternal grandmother currently holed up in her house (fully vaccinated, thank goodness). I think about my white grandfather and then I think about everyone's white grandfather. The ways we learn to talk about them: sorting pennies and playing computer chess, taking care of their progeny or truly loving their wives. I am not here to make any claims about anyone's origin story except for mine. Part of me knows the secrets are dark and hold shame. I am probably a product of someone's fetishism. I am a person who exists because of and despite white supremacy. And how do you decolonize when you are a product of colonization?

RELATED: Beyond "Joy Luck Club": Tamlyn Tomita on "Asian Americans" and the power of immigrant storytelling

I don't have answers, only questions at this point. I know that something horrible happened to my Japanese aunt that made her lose her mother tongue. I know that my white grandfather married two Japanese women: the first was my maternal grandmother, who died before I was born. I know that this grandfather thinks he saved her. They met in Japan when he wore a khaki Air Force uniform, according to a vague letter that gave me more questions than answers.

* * *

My mom once told me that people discriminated against her for being too white in her Hawaiian high school. Her last name was white because her dad was white. Her Japanese mother was hidden in so many ways. In the crevices of memories and stories, in a dark bowling alley snack bar working as a cocktail waitress, in a foggy story about her upbringing in a brothel, the way she died and no one but her new husband knew where she was buried. This woman does not show up on my mother's face much. One of my mom's eyes has a droopy lid — she jokingly calls it her "Asian eye." Before that asymmetry, she always identified as a half-white girl. The other half (the Asian half) invisible or ambiguous. Even her email address means half-(white) foreigner.

When my sister was little, we watched the movie "Corrina, Corrina," starring Whoopi Goldberg, and she was outraged at the way Whoopi's character is treated. She said, But we're all Black, except for mom. (We are not Black; our dad is Filipino.) In the early 1990s, "The Ernest Green Story" came out as a made-for-TV movie. My dad watched it in front of me, seven or eight years old. First day of desegregation and a girl spits the N-word at the main character, teenage Ernest Green. What is that? I ask my dad. He just says, It's very bad. Then she is the N-word, I tell him, but I say the whole word, pointing to the blonde bully in saddle shoes. I do not remember what he said to me next, but I got in trouble. I felt as if I'd done something wrong, but I did not understand what. These two examples are representative of our education about race and identity as children.

RELATED: Before Atlanta: The U.S. has a long and ugly history of violence against Asian women

When I was in my twenties I argued with my mom about that racial slur, a thing I had learned to keep out of my mouth, a thing whose history evaded me until I asked the right people the right questions, read and listened. I don't remember how it came up. Maybe it was the comfort with which it sat in her mouth. A round, heavy stone. She didn't use it as a slur, but referred to it, pronouncing the R, and when I cringed, she argued that words don't have power. She said this to me, a writer, and it was hard for me to guard my little heart and tell her, Oh yes, they certainly do! I probably said something about history and memory and hatred, about how a word like that doesn't exist for a person like her, so there's no way for her to really understand how it feels. At the end, I felt I made a strong point and she understood. I do not know if we could have a productive conversation like that today.

* * *

I thought talking to my 80-year-old conservative Filipina grandmother about police brutality and racism would be hard. She surprised me — she was incredibly receptive. She even told me a story about how police in SWAT team gear, with guns drawn, surrounded her townhouse once while she was at work. (She lived in a predominantly Black neighborhood then, and currently lives in a very white neighborhood, three houses down from my mom, her ex-daughter-in-law.) When I asked, Do you think that kind of response: having guns pointed at your house, was necessary? Do you think they would have done that in this neighborhood? She thought for a moment, and replied, No. I asked her to read "The Letter for Black Lives" in Tagalog. She has lived here since 1976 and speaks and reads English as well as Tagalog. I won't pretend that she didn't sow anti-Blackness in my childhood brain when she made comments about her Black neighbors, or that she doesn't uphold white beauty standards as a symptom of the Philippine colonizer's mentality. But acknowledging this country's "brutal truth," as James Baldwin puts it, is at least a step in the right direction.

My mom is different, somehow: harder to reach. The pandemic has not, as it has for many folks, allowed her to reassess the ways she might contribute to or benefit from a capitalist, white supremacist patriarchy. Instead it has intensified the rate at which she consumes conspiracy theories. Since last summer, my mom and I have argued about masks and vaccinations. I am for them; she is not. We step into our same worn rolls of argument, and I'm suddenly 14 again. She condescends to me: Use your brain. Think critically! She asks if I even know someone who has been affected by COVID-19? Yes. And are they dead? No. So that means, ostensibly, that because she is not personally affected (yet) and does not know people affected, that it does not exist in her reality. This seems to be her same approach to the damaging effects of racism and white supremacy.

RELATED: Sen. Mazie Hirono on Trump, anti-Asian hate crimes and her remarkable immigrant story

The last time I talked to my mom about racism I was in grad school, teaching bell hooks and Baldwin to white kids in Indiana. She told me that I was giving racists power by reacting or expressing my anger and exhaustion. She told me a story about her full-Japanese half-sister, my auntie, who would just let it roll off her back: One time someone bumped her in TJ Maxx and said, Watch it Toyo! She didn't let it bug her, my mother said. That same aunt once told my mom that sometimes she was surprised to see a Japanese woman in the mirror, that she expected to see a white woman. Maybe she didn't let it bug her because she didn't feel that it applied to her. What happens when you embody, celebrate, take pride in, and identify with the part that they are insulting?

In "Killing Rage," bell hooks describes a specific kind of rage in response to racism, and explains why she does not remain silent: "Rage can act as a catalyst inspiring courageous action. By demanding Black people repress and annihilate our rage to assimilate, […] white folks urge us to remain complicit with their efforts to colonize, oppress and exploit." The type of silence my mom wants us to perform does feel akin to both assimilation and colonization. The English in our mouths asks us to pronounce politely. We are conditioned to fake-laugh along for their comfort because it's just a joke. I understand that defense mechanisms are sometimes necessary for survival. However, absorbing the blows, the micro- and macro-aggressions, keeping your head down and working hard, not reacting: these do not empower me. These non-reactions do not give me agency. I refuse to prioritize a stranger's comfort over my own. I refuse to believe that my discomfort or anger gives an ignorant person power. Fuck that. I am not white-passing, I do not have a white person's last name. I am an obviously brown, tattooed person. I am visible in all the ways that make racist people squirm or grimace: Because I exist, and I am not sorry. In a time when six Asian American women were murdered, in a time with record hate crimes against AAPI folks, I am terrified and sick and exhausted. I am full of rage. I picture my own family's faces in each news story.

My mom and I have not spoken about the Atlanta shooting, and part of me wonders if she even sees herself (or her own mother or sister or daughters) in those women. The truth is that we haven't talked because it's difficult to talk to her. Any attempts to have conversations about race and history are ignored or evaded. I can't make assumptions about how she may or may not identify with these victims; based on the ways she talks (or doesn't talk) about race, I think she leans on her whiteness to distance herself from issues that POC typically experience. Maybe what I am saying here is that it's safer for her to identify and see herself as half-white, and it's part of her privilege that she can make that choice. However, the rest of us in the family are not half-white, so her denial can't cover us all.

* * *

I have not let my son spend time at my mom's house since she left the state for a conference in the summer of 2020 and posted a photo using the hashtag #NoMasks. I have a hard time talking to my husband about it without yelling. He flinches sometimes at the barrage of response meant for my mother. Can I say, too, that she used to be the most progressive liberal person I knew? She ranted angrily about George W. Bush when I was in high school, but has fully done a Kanye West-style 180. In the last 15 years I have had several impassioned arguments with her about words she should not use. Two weeks ago, she posted about Dr. Seuss's books, and claimed that caricatures of Asians do not offend her, but banning books sure does!

How do you mend a relationship when it feels like your own family denies your experience? How much impact can a conversation have when the person you are speaking with digs their heels in, doesn't respond, or responds by gaslighting? Our communication has been bruised since our first pandemic argument last summer. I craft carefully edited statements that I agonize over for days before sending, she responds with links to platforms that brag about their "lack of censorship" and promoting "free speech," despite the fact that it's often misinformation or hate speech, and videos that deny the effectiveness of masks or spread conspiracy theories about the pandemic. My sister's tactic is to send her jokey responses or treat her like someone passing out fliers on a busy street corner: No thanks! Have a good day! My three-year old is asking about seeing his grandmother. My dad asked me and my sister to please talk to her. What can we even say that hasn't been said already?

Shares