My friend Dante Barksdale was murdered in January. I failed him. I failed Dante. Saying anything other than that, in any other way, would be a performance. You could call it "performative," and you'd be right.

Performative speech and acts are everywhere; I hear them, see them, witness them every day. What does it mean? I think of leaders like Republican Sen. Mitt Romney out in the streets marching with Black Lives Matter protestors after the video of George Floyd being killed by a police officer went viral. Maybe Mitt was really moved by Floyd's killing. He did announce a plan for police reform legislation shortly after. But that's the kind of public stand he should have been taking, meaningful movement toward justice that these marches are meant to push him and other legislators into taking. Marching for him is a symbolic gesture, designed to catch eyes and cameras; it looks, well, a little performative.

RELATED: Why I won't stop writing about "trauma" to focus on joy

It's not just Senators like Mitt. I encounter it every day. The Black Lives Matter signs posted everywhere and painted on the intersections of major streets, the mass spewing of woke rhetoric, the infinite declarations of love for Black people by non-Black people across my timelines — it all strikes me as performative.

Walking through the market the other day with my mask on, a white woman ran me down, blocked my path, pulled her mask down — during a pandemic! — and flashed her Black Lives Matter shirt at me, telling me she purchased it in multiple colors . . . from Amazon. Maybe she recognized the top half of my head from a reading or a local TV spot or something? I don't know. Maybe she does feel that Black People Matter and she just wanted me, a Black person, to know it. But the amount of attention she demanded from me, a completely masked stranger shopping for fruit, struck me as performative.

Sometimes I laugh at the heightened sense of awareness our society suddenly shares — maybe to keep from crying, or because a chuckle is the only positive thing I can add to this collective optimism. If it's not the wave of "I love Black people" political speeches, it's the constant images of everybody winning at whatever they do. All of this looks equally performative: the people who never spill juice, not even during earthquakes, never eat a bad meal, never have a stomach ache, positive vibes only please! as they drive on the beltway and never ever miss an exit. These carefully curated realities I consume online everyday frustrate me. I mean, is everybody really doing that well after we've lost over 450,000 citizens to COVID? Come on. How are you traveling weekly, balling at five-star resorts and standing on VIP couches — without a mask — surrounded by crowds now?

RELATED: HBO doc shows how it's easy to make "Fake Famous" influencers

The young kids call an excessive amount of lying "cap." And seeing the massive about of cap being spread makes me want to call BS on all of it, to put a cap on the cap. The camera isn't rolling, I want to say, you can cut the act!

But I have no room to talk. I can't point a finger at Mitt, the partiers, or the lady in the market, because I'm performing too. I'm a professional at it. All cap, a mountain made of nothing but cap.

My friend Dante Barksdale, who also went by "Fat Tata," died recently. I go through this level of grief a lot, mainly because I choose to live in Baltimore, a small-big city with roughly 600,000 people that averages around 300 murders a year. It's not because I was raised here, or work here, or because my family is here. I live in Baltimore because I love it here. Dante did too. He worked and lived as a violence interrupter for Safe Streets, an organization that employs respected community members who work to prevent gun violence. Barksdale was so well known, so respected, and so beloved that news of his death made it all of the way up to the New York Times:

Mr. Barksdale, 46, went by the nickname Tater and was a nephew of Nathan Barksdale, the now-deceased narcotics trafficker known as Bodie who was an inspiration for the character Avon Barksdale in the HBO crime series "The Wire." Dante Barksdale drew upon his time in prison for selling drugs and his experience growing up in the projects for his outreach work.

Dante was loud and passionate, with an intense stare that hung off his perfectly round head. He was vocal with his views about what the city was doing and what we as a whole could do better. And people listened to him. So it wasn't strange to me when a friend who is also a reporter, followed by an activist, and then a city council member all contacted me when he was hanging on for his life after being shot. And as I collected these phone calls — all the stories of how great Dante was — I made a conscious decision to believe that he would be OK, even though my gut feeling told me that he wasn't. After his death was confirmed, the conversations kept raining: street dudes, reporter friends, community members, many of whom began or ended their calls with, "D, are you OK? Are you good? Are you going to be OK?"

Easy as it is to elect a white president, graceful as an Olympic figure skater, I parted my lips and I lied.

And I don't offer a simple lie: "Yeah, I'm OK." That's not enough. I lay it on thicker than grits in a Georgia diner.

"Oh, I'm am blessed, brother," I lied. "And the clouds will part and God will shine a light on all of us, and we will feel that light, be energized by that light, anointed by the light, and left with the power from that light to guide all of our people out of the darkness that raps our community! Amen! Amen! Amen!"

But I don't feel light; I feel dark. And I don't want to talk. I want to ride around alone and listen to Scarface rap about death while fighting back tears. I want those tears to fall, but I don't let them because I must perform, even if nobody is watching.

RELATED: "We're all carrying some level of mass grief as Black people"

I take all of the calls. I imagine that the person on the other end of the phone is inspired by my soliloquy, motivated to fight the good fight as soon as we hang up. They are performing, too. They are lying, too. Our performances mix together like tonic on gin whirled around in the glass. We egg each other on with hope, our tirades pointed at the system, offering each other, "you'll be OK," even though we won't. And what's worse, our performances are appropriate responses to death and grief. We almost never ever tell people how we really feel and everybody is OK with that, even you.

Nobody wants to hear how you're really doing. They want to hear how great you are doing, and how your inspiring social media posts reflect your actual life: the perfect latte and gourmet doughnut drizzled with honey, the vacation house in Tulum, because that makes us smile. This is probably why Dante never asked me, "How are you?" He would ask instead, "Are you good?"

We would talk a few times a month, on and off. I was supposed to pull up at his Christmas toy dive, but didn't because of the pandemic, a decision I now regret because I'll never see him again. The last time I hung with Dante was pre-pandemic. I walked into the food hall and spotted Dante in his bright orange Safe Streets polo, elbow deep in conversation with a government-looking pantsuit lady, a politician or political aide, probably. He didn't spot me so I walked up behind him and purposely bumped his right shoulder with mine. He spun around to see me squared up and throwing punches. He blocked them, laughing, throwing punches back before pulling me in for a bear hug.

I apologized to the lady for interrupting the violence interrupter.

"Do you know D Watk?" he said to the woman, who smiled and shook her head no.

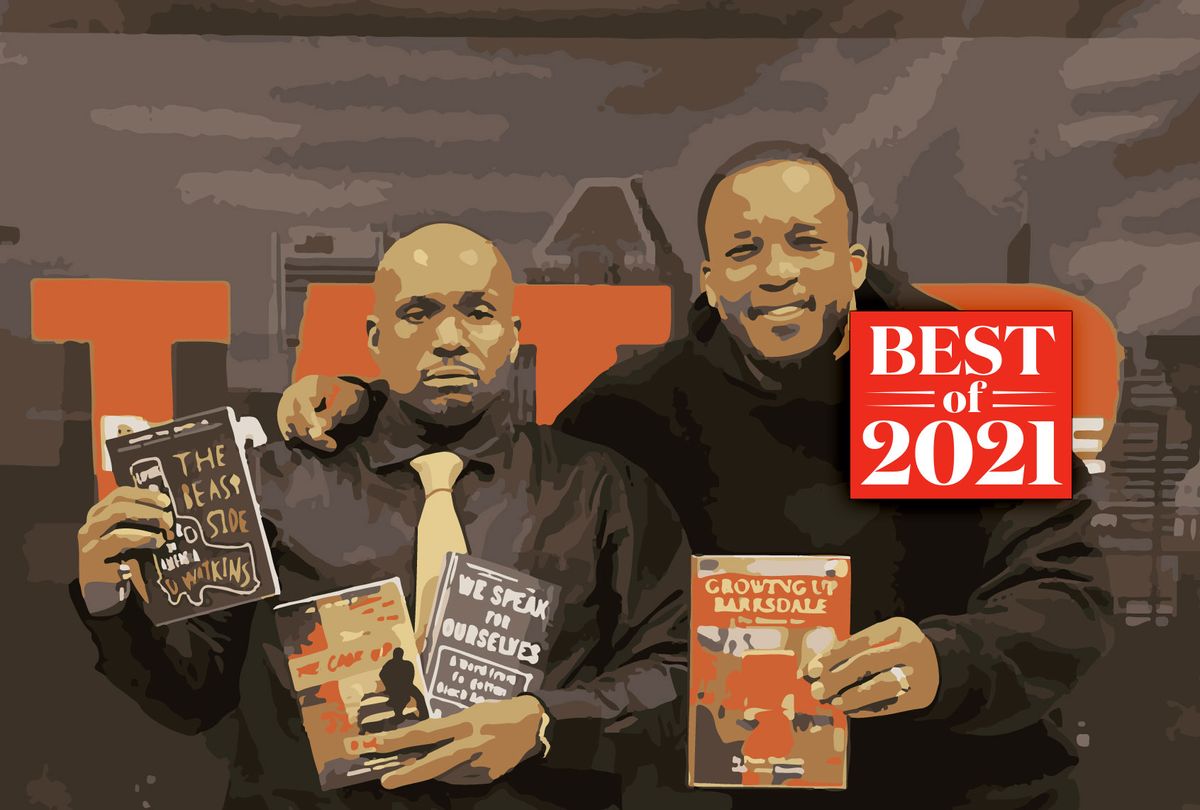

"You gotta know D Watk!" he said. "This the brother that helped me and my coauthor while we was doing my book — this my boy! He the man!"

I shook her hand, apologized to both of them for interrupting and told Dante I'd be in the corner working and eating. He came over about a half an hour later and told me how his book sales were going, about life, about Safe Streets, how our politicians are constantly fumbling the ball, and his plans for stopping the murders.

As we got up, he paused and asked, "Yo, are you good out here?"

"Of course," I responded, fixing my jacket.

Dante grabbed my arm.

"Nah bro, are you OK? You taking care of yourself?"

I sat back down and told him that I was maintaining, adjusting to fatherhood. And that I was worried about the future of the city and my place in it, if the things I do or try to do to help Baltimore even mean anything.

"I feel lost out here," I sad. "Man, they killed my bro Dee Dave. I'm just lost."

"I heard about that. Dee Dave was a good guy, but the kids love you Watk," he said fiercely. "They see D Watk being positive and coming around the way, and some of them want to be positive too, cuz of you. Don't ever forget that. Shit, your book made the book shit real for me! We only getting better cuz!"

"You know how it is," I said.

"Man, I'm out here every day," Dante said. "You know I know. Keep doing what you doing man. You from my projects man, so I gotta look out for you."

"I keep telling you bro," I laughed. "I'm not from Lafayette, I'm from Down Da hill."

"I know you and all ya big head-ass cousins from Lafayette," Dante spat back with a smile. "So we claiming you, superstar. But for real, keep inspiring the kids man. It matters."

Dante probably had to perform at times just like the rest of us. But he was still one of the few people who would tell the truth about the things you don't want to hear. On one of his last Instagram posts, he explained how more than 1.2 million Black men died at the hands of other Black men over the last 40 years. And he wasn't saying it the way misinformed people try deflect arguments against police violence, or to act like White on White crime doesn't exist. He was saying it because he was sick of us dying. He knew the issues and where they came from, but he loved us so much that he refused to perform when dealing with us because he wanted us to do better, and because it was the truth that we didn't want to hear. And we failed him.

Dante risked his life and died in front of those he tried to protect in a city where law enforcement lacks the imagination to understand how important his work was. They failed him, too. Many cops view Safe Streets with the same contempt they have for the people they arrest, even though that organization that Dante was so proud of actually makes their job easier. Baltimore failed Dante. We all failed him with no way of making it right.

And yet we continue performing, every single last one of us. And I honestly don't see an end to it. Because after the pain of his loss, after seeing all of the crying people, the hurt family members, it still remains hard for me to say, "I'm hurt, too."

I don't want to do anything or think about anything, because I'm hurt too. These deaths honestly break off whole chunks of me. Every week, every month, every year.

I know enough to know that the world around me doesn't want to see the hurt I have for Dante and the dozens of other friends I've lost over the past few years. The world doesn't want to see it about as much as I don't want to share it, so we all continue to perform instead.

I know I need to try to deal with the pain rather than sprinkling fake positivity on everything. Talking about the pain briefly or glossing over it in my writing is not dealing with the trauma.

Until I stop performing and deal with it, I will continue to let Dante down. We'll all continue to let Dante down.

Shares