Reciting what was even by 1990 a familiar litany, a Princeton professor, in a book called “The Death of Literature,” accused advanced writers of the past 200 years of wanting nothing to do with bourgeois industrialized society except to attack it:

Generations of authors have lived out the poet’s role that Wordsworth created, in life and poem, withdrawing from industrialized society and rejecting its materialist values. Sometimes they took up their stance on the left, like Blake and Shelley, sometimes on the right like Yeats and Pound, but always, like Joyce’s Stephen Dedalus, they refused to bow — non serviam — to the bourgeois family, religion, nation, and language that they felt cast nets over their souls.

To the writer of those words, the apparent triumph of bourgeois (capitalist) democracy over fascist and communist rivals signaled what was soon to be called “the end of history.” By opting out, advanced writers had succeeded only in marginalizing themselves. Their marginalization had little to do with rejecting bourgeois democracy, however. Rather, bourgeois democracy had marginalized them for failing to measure up economically. The same fate has befallen classical music, absent any explicit rejection of bourgeois democracy, though other face-saving excuses have been invented. On the other hand, marginalization has not befallen the most successful visual artists (whatever their politics), whose work can garner exorbitant prices and therefore respect for the vocation.

Donald Trump did not insist he was a billionaire just to satisfy his own ego. He knew that status would increase his authority and popularity. Despite their anti-establishment pose, the people who rallied around him align themselves with wealth, power and whiteness. They delighted in seeing Trump flaunt his wealth and use his office to increase it, emoluments clause be damned. Their view of American greatness is just a somewhat Dorian Gray-style portrait of the official view. The objects of their resentment are the people they see as threatening their position in the pecking order. That’s the way resentment (or ressentiment) often works — not upward, as Nietzsche says, but downward.

Nor are Trump supporters against big government. They simply demand a government that will keep their inferiors where they belong. They favor giving the military, the police and the agencies that spy on us whatever they want, while starving social programs. The media adopt their labeling of this repressive agenda as “small” or “limited” government. But who was it who launched the campaign against “big government”? None other than government itself in the person of Ronald Reagan, who also launched the campaign against “government bureaucrats,” the term of art reserved for those in government who persist in taking their responsibility to the public seriously. The old Cold War slogan still holds: “Better dead than red” (communist or socialist). Sooner death than government of the people, by the people and for the people.

RELATED: Rudy Giuliani’s big reality-show reveal: The “billionaire” in the White House is broke

If government were serious about alleviating the problem Trump supporters pose, of course, it would stop its lying and secrecy, and the aggression and conspiracy theories they inevitably spawn, and pursue policies that benefit the majority.

Bourgeois democracy divides us into winners and losers. It loves winners and despises losers. Its apologists loathe Trump for making this unseemly fact so obvious, among other reasons. Taking the wisdom of the system as a given, critics find their own reasons to fault the arts it discriminates against, just as the poor and the struggling have always been made to bear the blame for their difficulties.

Like traditionalists such as Alvin Kernan, the Princeton professor quoted above, many cultural progressives have embraced a standard of redemptive art. It’s not the canon of Western civilization so much as works that can be seen as deriving from or on the side of the oppressed, who are untainted by history. For these commentators, the well-publicized “failure” of 20th-century modernist works to rival popular culture in terms of audience appeal exposed not a particular sterility and moral deficiency, as traditionalists claim (see, for example, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s speech “The Relentless Cult of Novelty and How It Wrecked the Century,” published in the New York Times Book Review in 1993), but the emptiness of high art’s claim to superiority, whatever its period. (Once upon a time, the U.S., as leader of the “free world,” officially favored avant-garde experimentation to show our superiority to the communist world and its ideological straitjacketing of art.) Just another way oppression has been rationalized. In the culture wars of our day lies the promise of a brighter tomorrow.

Progressives have made an ambitious, concerted effort to deflate the idea of artistic masterpieces and artistic genius as inherently reactionary (at least regarding the established canon) and to identify popular culture with progressive politics. By stigmatizing high art and idealizing popular taste, they claim to be striking a blow for true democracy — and not just pandering, as advertisers, politicians and the media do as a matter of course. They are the advocates of laissez-faire in culture.

The idea that to criticize popular taste is anti-democratic is the premise of Andrew Ross’ enormously influential “No Respect: Intellectuals and Popular Culture,” published in 1989. Ross’ claim that 20th-century American intellectuals had no respect for popular culture is false, but he is unconcerned with their praise of particular works or artists, perhaps seeing it as expropriation or incipient canon creation. What he actually objects to is their presumption in making judgments at all. They may not have spared “elitist” high culture, either, but then, high culture deserved it for its pretensions. Ross views popular culture as the direct expression of popular taste and thus above criticism.

For him, the only authorities worth attending to about popular culture are French intellectuals (Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Jacques Lacan and so on) and their followers. The fact that these authorities do not address the general public, unlike the intellectuals Ross pillories, does not raise his democratic hackles. Why bother engaging the public when you can just co-opt it?

Ross cherry-picks examples to associate a critical stance toward popular culture with sexual and political conformity while celebrating rock, punk, camp, pop, porn and romance novels as liberating and transgressive. Though Ross mocks the idea of the heroic dissenter he associates with “vanguardist” critics of popular culture, he presents Andy Warhol as a culture hero, exemplary because he identified himself with popular culture.

“When others are giving up democracy, or defining [high] culture as its antithesis … there must be loyalty to both,” British social critic and novelist Raymond Williams said in the 1950s. Democracy and culture are still often seen as antithetical, but culture is now likelier to be considered the more dispensable of the two — or at least, supposedly democratic popular culture is viewed as the aesthetic equal, and the moral or political superior, of “elitist” high culture.

Given this shift, traditionalists have been anxious to reassert the superiority of high culture to popular culture, or at least to those examples of popular culture they find morally or politically repugnant. They charge modernist art not only with fostering the spiritual climate for Hitler and Stalin but also with allowing popular culture to run amok and become debased.

When people refer to the failure of 20th-century modernist art to reach a large audience, what they mean is that it didn’t find an audience large enough to counter the pop-culture audience. But who isn’t part of the pop audience, at least some of the time? The art of earlier centuries is spared that devastating comparison. The names of its creators can still be counted on to evoke an awe that carries with it an illusion of bygone social unity. Thus, Solzhenitsyn invoked Racine, Murillo, Raphael, Bach, Beethoven and Schubert as the “spiritual foundation” of their times, though their work was known to far fewer people in their own times than in subsequent centuries.

In the academy, high culture’s star has fallen (broadly speaking) as that of popular culture has risen. Once a good deal of popular music became identified with political protest, starting in the 1960s, popular culture was in a position to eclipse high culture in prestige. The fact that for much of the 20th century, pop culture was regarded as inferior to high culture also added to its luster — a sort innocence by disassociation. Its economic superiority clinched the matter. If a work of art is only or mainly a political document or source of moral inspiration, then the larger the audience it reaches to inspire or enlighten, the greater the work and the artist. Popularity by itself tells us nothing about how people respond to a work — and whether or not they understand it as “political” — but some cultural progressives have accepted it as the supreme standard. Down with cultural hierarchy — and up with economic hierarchy.

In his influential study “Highbrow/Lowbrow: the Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America,” historian Lawrence Levine argued that until the second half of the 19th century art in America was regarded — rightly, in his view — as no different from any other form of entertainment and subject to the same measures of success. Then the arbiters of culture stepped in, expropriated art from the people and sacralized it. I don’t believe Americans ever embraced art as Levine says we did, or were later cowed by the arbiters of culture. To me, those claims contradict each other.

Pop culture has become accepted as genuine popular expression rather than as potentially exploitive. That view that offers something for everyone: the exploiters, who always said they were here to give the public what it wants; the celebrators of pop, who can cozy up to success and celebrity while feeling virtuous about it; and the elitists, who can take masochistic pleasure in having their low opinion of popular taste confirmed. In this context, it has become taboo to view the public as vulnerable to manipulation. You see, elitists fed us that patronizing line simply to mask their attempts to cow us into buying the mystique of Art.

When I began this essay, early in my late-life awakening to economic matters (a strange admission for someone who made his living working for business publications), cultural progressives’ credulity about the market just made me uneasy. Now, it floors me: To demystify Art with a capital A, progressives embraced the mystification of the Market with a capital M.

Popular culture is considered democratic because of its superior salability. It meets the market’s most important test: people will pay for it on a mass scale. The marketers of popular culture go all out, while promoting the idea that their efforts have little effect: We are all sovereign individuals, and far too sophisticated to fall for crude manipulation! We agree, of course — just as we tend to buy into the flattery of demagogues — and so does anyone with an interest in disparaging high culture, especially in its more vulnerable 20th-century manifestations.

RELATED: The “death of adulthood” is really just capitalism at work

How many of us, enjoying feeling part of the crowd or wanting to share something with others or simply out of curiosity, read books or watch movies and TV shows just because they’re popular? Who doesn’t? We are social, imitative animals, after all. We are only too easily led, always questioning why we should not be like the other animals instead of being “fated to wide-eyed responsibility in life,” as D.H. Lawrence put it in his poem “Man and Bat.” Herd animals who follow the crowd: That’s what the social order prefers us to be, and what pop culture conditions us to be.

Unlike pop culture, high culture has been insulated from the market, judged not by salability but by “aesthetic” qualities dreamed up by high culture’s “priests.” The “people” have had no say in the matter. Aristocratic in origin, high culture accommodated itself to the rise of the middle class while remaining elitist and complicit in inequality. Did two centuries’ worth of anti-bourgeois artists rid us of sexism, racism and inequality? QED. It must be admitted that the belief in art’s sovereign and transforming power, evident in both romanticism and modernism, encouraged millennial hopes that have now been transferred to pop culture.

Cultural progressives such as Levine view the market as the great leveler, working to democratize culture, but never to control it or to reinforce hierarchy. Only the “arbiters of culture,” the “culture guardians,” have that insidious power. However flawed our democracy may be otherwise, popular culture is understood to be perfectly democratic. So those progressives, who preach against viewing culture in isolation from its social context can celebrate the ascendancy of pop culture even as they deplore the surrounding political and economic climate. For them, high culture, despite its marginality, reinforces the power structure, whereas pop culture — by any standard, a pillar of the global economy — is vital, subversive, transgressive, even revolutionary.

In this worldview, to venerate elite artists is idolatry, but to worship popular artists is good for the soul. To conflate artistic and human worth is wrong — except when art is sanctified by popular success.

For some, artistic greatness is inseparable from financial success, as well as from political correctness. For example, Alex Ross has blamed classical music itself for the precarious position it has long occupied. When, with Richard Wagner, orchestral and operatic music began to consider itself superior, universal and difficult, Ross explained in a 1996 New Yorker essay, “it stumbled badly in the new democratic marketplace.” If classical music hadn’t “overstepped the mark and turned megalomaniacal,” presumably it would have prospered, as pop music has done.

It doesn’t matter that Ross’ explanation makes no sense. Did the supposed megalomania of classical music only begin with Wagner? In what sense was he a universalist? And wasn’t classical music’s self-ascribed reputation as superior, universal and difficult aid its popularity, at one time? Don’t those descriptions and that marketing strategy apply today, to the nth degree, to the treatment of pop culture both inside and outside the academy? The aesthetic criteria that were supposedly invented to support high culture’s claim to superiority have not been scrapped. They have been repurposed and pressed into service on behalf of pop culture.

In any case, once we accept the premise that democracy and the marketplace are equivalent, we’re sunk. We’re left with no choice but to fault classical music, for example, for failing to prosper economically. High culture is now in the same position of presumed moral inferiority that poor people have always endured within bourgeois democracy.

Cultural works that succeed in “the new democratic marketplace” — by making a ton of money — are literally understood to be good for us. They are not led astray by the artist’s delusions of grandeur, alienating a virtuous, right-thinking public. They are modest in their intentions, like the (truly Wagnerian) novels of Ayn Rand. The cultural consumer, unlike the consumer of other products — or the political consumer — exercises sound judgment and is not swayed manipulation. She is the rational actor of classical economics, as imagined for instance by Adam Smith.

This belief in a democratic marketplace belongs with belief in a self-regulating market, as an illusion by which our economic system maintains itself. But Andrew Ross’ argument does make sense, in one specific way. It expresses the widely shared feeling that high culture had it coming for having offered itself as a substitute religion, a “royal highroad of transcendence,” in novelist Walker Percy’s phrase. In that light, the use of Wagner as example made perfect sense. The true substitute religion is popular culture.

Alvin Kernan, whose description of the adversarial literature of the last two centuries I quoted at the outset, believed that artists in bourgeois industrialized societies no longer had any business dabbling in social criticism. An artist fortunate enough to live in such a society had an obligation to support the system, or at least to refrain from questioning it, because bourgeois democracy represented the best of all possible worlds, and was to be protected and nourished at all costs. To criticize the system, in that view, was to invite the commissars and the concentration camps. Critics are dupes, fellow travelers of Hitler and Stalin, totalitarians in spirit, nihilists. (Kernan was a decorated veteran of World War II who wrote extensively about his war experiences.)

The Marxist historian E.J. Hobsbawm, in his 1994 history of the “short” 20th century, “The Age of Extremes,” tried to have it both ways. On the one hand, he derided the idea that aesthetic quality was a myth and that sales figures were the only valid measure of a work of art. On the other hand, he treated aesthetic factors as negligible compared to political considerations. Hobsbawm’s own artistic preferences all had political underpinnings, and he was sarcastic or obtuse toward artists who lacked the right political associations.

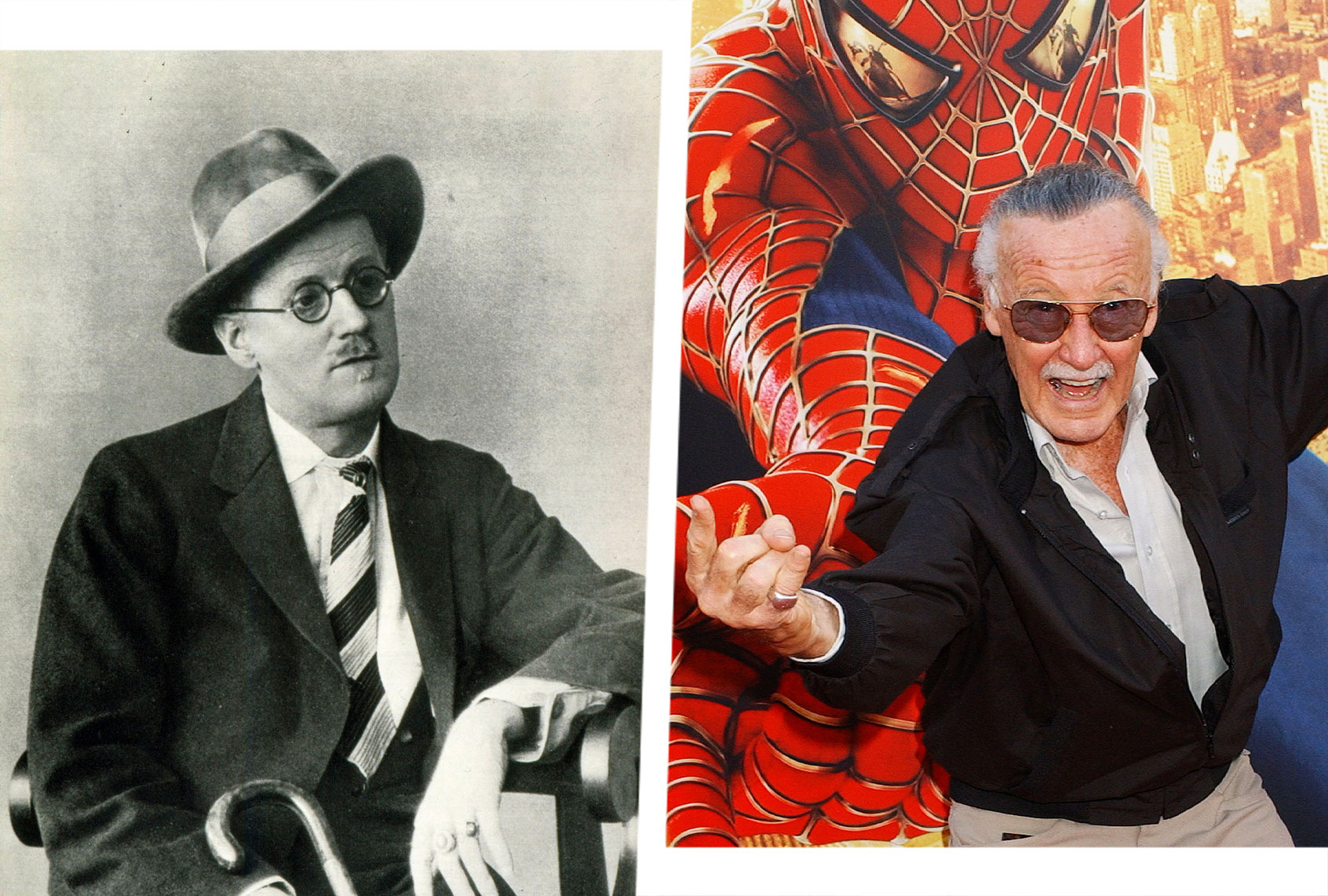

Many progressive critics, also in the name of democracy, similarly want to discourage artists from expressing views or attitudes contrary to their own. They believe an artist’s democratic duty is to please the virtuous, right-thinking public, for which he or she will be duly and amply rewarded. Aesthetic distinctions unsupported by box-office success are a political inconvenience, an obstacle to be gotten around. Artists and works popular in their own time are the frontrunners in the immortality sweepstakes, and the more popular they are, the better their chances. So we can never disqualify Jackie Collins or Britney Spears or the Marvel movies, for instance, on suspect aesthetic grounds.

RELATED: Peak superhero? Not even close: How one movie genre became the guiding myth of neoliberalism

Shakespeare scholar Gary Taylor used the Jackie Collins example in his book “Cultural Selection: Why Some Achievements Survive the Test of Time — and Others Don’t” to emphasize the “obvious but embarrassing truth … that we don’t know what the future will consider important.” However, because “cultural selection,” in Taylor’s view, requires the stimulus to memory that contemporary popularity can provide, we lessen the chance of being wrong in our judgments by going along with the crowd.

Taylor discusses the popularity of the movie “Casablanca” upon first release, citing its box-office success, its three Oscars, and the 21-week run of its theme song, “As Time Goes By,” on the Hit Parade as evidence of “how people did respond before their ‘parents’ told them how they should respond,” in other words, before the movie became a “classic.” To heighten the contrast between the first response and later ones mediated by authorities (“parents”), and therefore compromised, Taylor in effect minimizes contemporary conditioning factors — publicity, advertising, reviews, word-of-mouth, sociability, World War II. The possibility that “Casablanca,” despite its continued popularity — the strength of its stimulus to memory, in Taylor’s terms—may be inferior to less popular movies is not considered.

Is judgment determined solely by enduring popularity, so that it’s futile to criticize “Gone With the Wind,” say, on the grounds that it falsifies history in a way that has proven harmful — as did its popular predecessor, D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation”? That’s not to suggest that political considerations should entirely determine our judgments about art, only that the criteria for such judgments are always dynamic and conditioned by multiple overlapping factors.

RELATED: The Confederate mystique: White America’s toxic romance with a criminal regime

Most of the people in the original audience for “Casablanca” still understood movies as marketable commodities, disposable goods. But a great many people who have watched “Casablanca” within the last 50 years or so grew up with the idea that movies are an art form — the modern art form, in fact, and a beacon in a dark time. What Racine, Murillo, Raphael, Bach, Beethoven and Schubert were to their times, according to Solzhenitsyn — a spiritual foundation — the movies, a popular and collaborative art, have become since.

What accounts for that change in public perception and what part has it played in the lasting reputation of “Casablanca”? Taylor doesn’t say, but although he is comfortable crediting the survival of works of art to the wisdom of the contemporary public, to the workings of godlike technology and to those who make or keep these works available to the public, he is disinclined to acknowledge the role of criticism. Critics, after all, are those who presume to make aesthetic distinctions regardless of popularity, or even in defiance of it.

Taylor, clearly thinking in terms of a mass audience, describes Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring,” one of the composer’s best-known works and a landmark of modernism, as unpopular. He cites it as an example of art that is too complex for most people, a complexity made possible, and therefore (in his view) inevitable, by the increased capabilities of music notation and performance. According to him, “Rite of Spring” was created for — and can only be enjoyed by — a small group of connoisseurs, although Stravinsky himself wanted to reach as large an audience as did Tchaikovsky, Taylor’s example of a popular classical composer.

Some progressives, like some traditionalists, have taken up the banner of “accessibility” in works of art, in opposition to modernist complexity or “difficulty.” Some give this standard a further ideological twist, associating it with women artists, LGBTQ artists or artists of color, and thereby associating complexity with white heterosexual males. Implicit in Taylor’s treatment of Stravinsky is the idea that although newfound freedom went to the heads of modernist artists (which was understandable), art should never be difficult to like or understand. It should seek the largest possible audience, rather than a limited one. But who is Taylor to say that “Rite of Spring,” which he seems able to enjoy without being a professional musician or musicologist, is beyond the grasp of “most people”? And how does that statement square with his professed belief in popular taste?

To Lawrence Levine, the idea that we should approach works of art as individuals instead of as part of a group is an aspect of the divide-and-rule strategy crafted to serve elite interests. Levine is not interested in individual responses to art — he cites none in “Highbrow/Lowbrow.” When he refers approvingly to the American audience’s involvement with art in the early 19th century, he refers to boisterous, often belligerent, occasionally violent and predominantly male crowd behavior, not unlike that associated with professional or college sports in our own time. That audience was quick to take offense if they thought their country or their dignity was being insulted, or they weren’t getting what they’d paid for. Some confused plays with reality and wanted to intervene in the action. Others freely hissed, booed, cheered, stamped, applauded, threw things, ate, talked and expectorated their way through performances.

Levine interprets this conventional rowdiness as the American audience asserting its democratic fellowship with the audience for Shakespeare’s plays and Italian operas in earlier times and places, and contrasts that to the “passivity” of later audiences cowed by the culture guardians. Where the culture guardians saw an uncivilized mob, he sees unspoiled aficionados. He is benevolently condescending and professorial, inviting us to share his delight in the early American audience’s “wonderful” naiveté and truculence. His vision of virtuous solidarity among ordinary Americans may owe more to Frank Capra than to Karl Marx, and his model of audience involvement with art seems as coercive to me as the model he deplores.

RELATED: The creation of William Shakespeare: How the Bard really became a legend

Levine equates personal, private and largely silent audience involvement with passivity because he sees it as representing defeat in the struggle against the culture guardians. In his view, the more intense the private emotion, the more complete the audience capitulation. This becomes clear when he approvingly cites settlement house pioneer Jane Addams’ criticism of the “passive” absorption of shopgirls in watching movies, though Addams criticized their taste entirely on other grounds. (Because they should have been getting more fresh air and exercise.)

When Levine describes, as a crowning outrage, a 1914 Boston Symphony performance of Schönberg’s “Five Pieces for Orchestra,” it’s a tossup whom he views with most impatience: the polite, unprotesting audience; conductor Karl Muck, who programmed the work from a sense of cultural duty; or with Schönberg, for perpetrating such an affront in the first place.

Levine’s distrust of individuals is something he shares with the culture guardians he criticizes. They tried to dictate how we should receive art, how we should value it and which works and artists we should admire. As educators of the people, they were disinclined to allow individuals to decide for themselves. Levine distrusts individuals because they can be seduced into admiring art as above them, and into admiring works that perhaps manifest indifference to or contempt for “the people,” or other incorrect messages. To respond to art as we have been conditioned to do divides us rather than unites us, and encourages unwarranted feelings of superiority. Levine, no less than the culture guardians, holds to an idea of the people that excludes himself. The upshot, once again, is that we cannot trust ourselves where art is concerned, but must seek expert guidance.

Who will be our new improved culture guardians? Professional historians, for one. Levine’s democratic principles are further compromised by academic chauvinism. Despite what he says against professionalization and specialization and in favor of amateurs and lay practitioners, Levine was an academic historian asserting the claims of his discipline to the field of “expressive culture,” to which amateurs like Dwight Macdonald (whom Levine views with tremendous condescension) once laid claim. Among the cultural institutions Levine subjects to critical scrutiny — libraries, museums, concert halls, opera houses, public parks — colleges and universities are conspicuous by their absence.

For Gary Taylor too, teacher knows best. “Cultural Selection” culminates in an attack on Richard Nixon, who Taylor believes we must learn to remember as evil for the sake of our moral and political health. What had seemed an exposition of politically correct aesthetics, uncomplicated by personal feeling, finally becomes a sermon. Because of what Taylor doesn’t allow himself to say earlier, the result is self-contradiction. A writer who can’t bring himself to breathe a word against Jackie Collins or “Casablanca,” in deference to popular taste as measured by the marketplace, thinks it essential for a twice-elected American president to be understood as the epitome of evil. But why is the judgment of the ballot box more open to question than the judgment of the box office? Shouldn’t he remind us again that we don’t know who the future will consider great, and cannot presume to judge?

Perhaps Taylor, and other cultural progressives, imagines a kind of quid pro quo: I say nice things about Jackie Collins — or, latterly, about Spider-Man and Taylor Swift — to prove my belief in the people. They will vindicate my faith in them by repudiating the political right. It’s a special plea for a form of moral reckoning, one that worship of the marketplace has made impossible.