There is a train of thought that posits that the omicron variant is a sort of grand finale, the last major strain of COVID-19 to sweep through the global population during this pandemic. Some scientists are even predicting that that will happen; they speculate that the highly transmissible strain could bring us closer to a future where this disease is endemic, meaning that it will always among us (like the flu), but we will have it largely under control.

That is one possibility. There is another prospect, one that is troublingly plausible when you consider that scientists know so little about omicron's origins. Perhaps, rather than signaling the beginning of the end, the omicron variant might simply be the first of more mysterious mutant SARS-CoV-2 viruses to come. Scientists who spoke to Salon expressed precisely that concern — and laid much of the blame for omicron at the feet of those who refuse to follow and enforce basic public health guidelines.

First, though, experts emphasized the importance of the scientific context here. The public has to understand how strains like omicron are created in the first place.

"While it has been common to say that omicron arose 'from nowhere,' such a statement could be perceived as expressing both privilege ('nowhere' because it wasn't 'here'?) and forgetfulness (of the lessons we should have learned already)," Dr. Stuart C. Ray, from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine's Division of Infectious Diseases, told Salon by email. "The conditions that give rise to such evolution persist in the makeup of the virus and our global community."

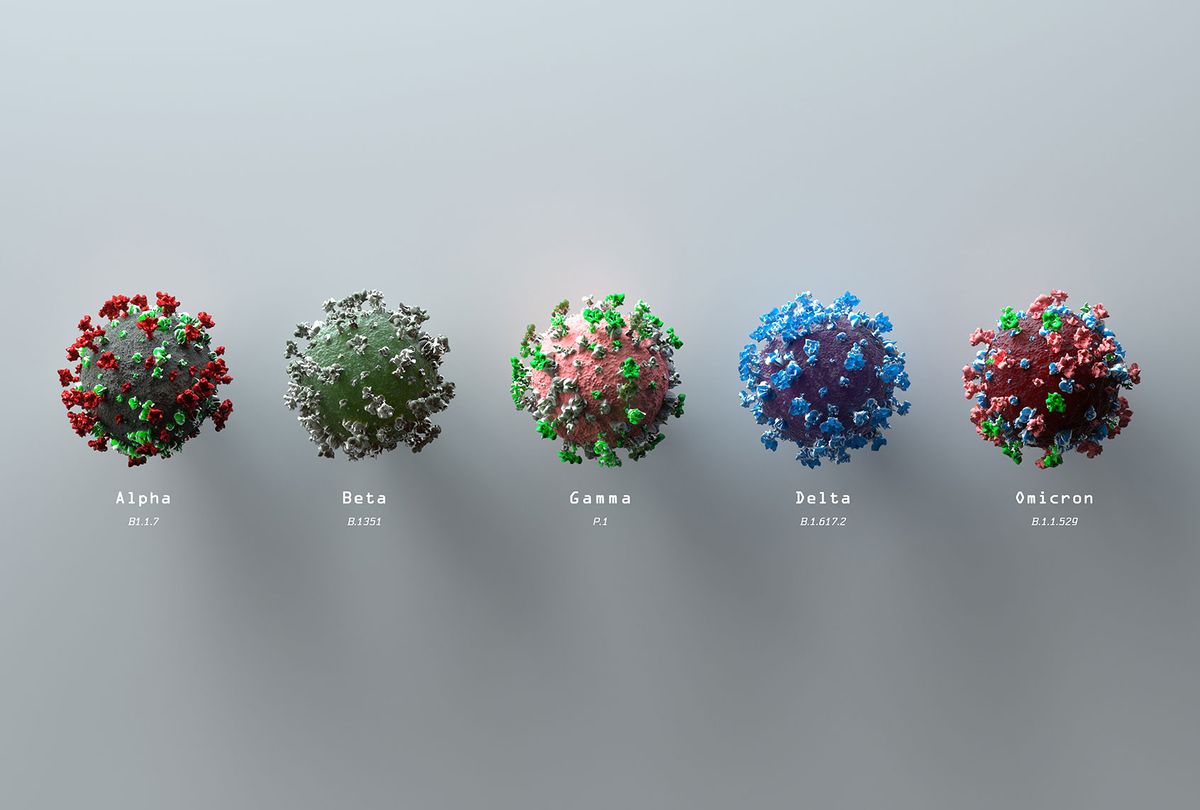

As Ray pointed out, a number of COVID-19 variants popped up in late 2020 that had unexpected mutations — these included the alpha, beta and gamma variants — and scientists struggled to understand those adaptations. The delta variant, which quickly became the predominant strain in the United States, posed unique challenges because it did not arise from alpha, beta or gamma "but from something more ancestral."

For all of these variants, however, "the number of changes in the genome was striking, as was the pattern of changes both in terms of shared and new features," Ray said. It is, in addition, "perhaps unsurprising" that they arose in areas with lower vaccination rates because it is possible that sequence evolution in RNA viruses like SARS-CoV-2 is linked to how often they can replicate.

"In that context, omicron seems more of the same," Ray explained.

Dr. Alfred Sommer, dean emeritus and professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, told Salon that he believes we can expect more mutant coronaviruses — and that this will be driven by low vaccination rates.

"Yes, it is likely another SARS variant, or even more radically different COVID-related virus will emerge sometime in the future," Sommer wrote to Salon. "'Variants of the present COVID-19 strain will keep appearing as long as the virus is circulating in the population; especially in large, unvaccinated and previously unexposed populations that have little resistance to infection. These 'variants' will contain new mutations of the present COVID-19 strain that might make them more infectious, more deadly, or more resistant to immunologic responses to earlier infection."

Sommer also identified another possible factor that could lead to more COVID infections. There could be a new COVID mutant that "jumps" from an animal host into a human, one that is distinct from COVID-19 but spreads just like that disease and the coronavirus behind the SARS pandemic of 2002 to 2004.

"That previous version was much more lethal, but much less infectious than COVID-19, which is the reason it was able to be 'bottled up' much more quickly and infected far fewer countries and populations," Sommer told Salon.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

That parallel between SARS and COVID-19 — and, more specifically, the fact that humanity's ability to cope with each pandemic varied so wildly based on such minor factors in each virus' makeup — underscores how little human beings really understand about viruses. This makes it far easier to be taken by surprise by a mutant. As explained by Dr. Russell Medford, Chairman of the Center for Global Health Innovation and Global Health Crisis Coordination Center, there is quite a lot that remains mysterious to scientists.

"Despite extraordinary and rapid scientific advances that have led to the development of effective COVID-19 vaccines and therapeutics, the rise of the omicron variant vividly illustrates that our understanding of the biology and epidemiology of SARS-CoV2 virus is very much a 'work in progress,'" Medford wrote. "While there are rare examples of viral eradication of endemic viruses such as smallpox, SARS-CoV-2 (with omicron today and new variants in the future) is most likely to be with us for many years as a global, seasonal endemic virus akin to influenza."

He added, "Fortunately, it is a question of when, not if, our growing knowledge enables us to effectively mitigate the impact this virus has on our health, our economies and our society."

In addition to increasing our knowledge about virology, humans will also have to follow the public health guidelines that can contain the COVID-19 pandemic.

"We know that vaccination, ventilation, high-quality and well-fitted masking, and concerted public health measures can curb infection and spread (and, thereby, evolution), but these have been applied in disparate and inconsistent ways," Ray wrote to Salon. "We also know that it's possible that SARS-CoV-2 variation – included the type seen in variants of concern - may arise in people who have reduced immunity and persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection."

Ray later added that there are a number of lessons people should learn, such as reducing vaccine inequality so that variants will not have the ability to arise merely because populations lack access to the medical resources needed to protect themselves.

"We don't appear to have the tools or will to eliminate SARS-CoV-2, but we do need coherent and nonpartisan plans to limit evolution of new variants, protect the vulnerable, and reduce disruption of our critical support systems," Ray explained.

After all, as Dr. William Haseltine told Salon, these COVID-19 variants are here to stay.

"It's a certainty," the biologist renowned for his work in confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic, fighting anthrax and advancing knowledge of the human genome told Salon. "It's not a fear. There will be more variants. It is as close to a certainty as you can get."

Omicron's rise:

Shares