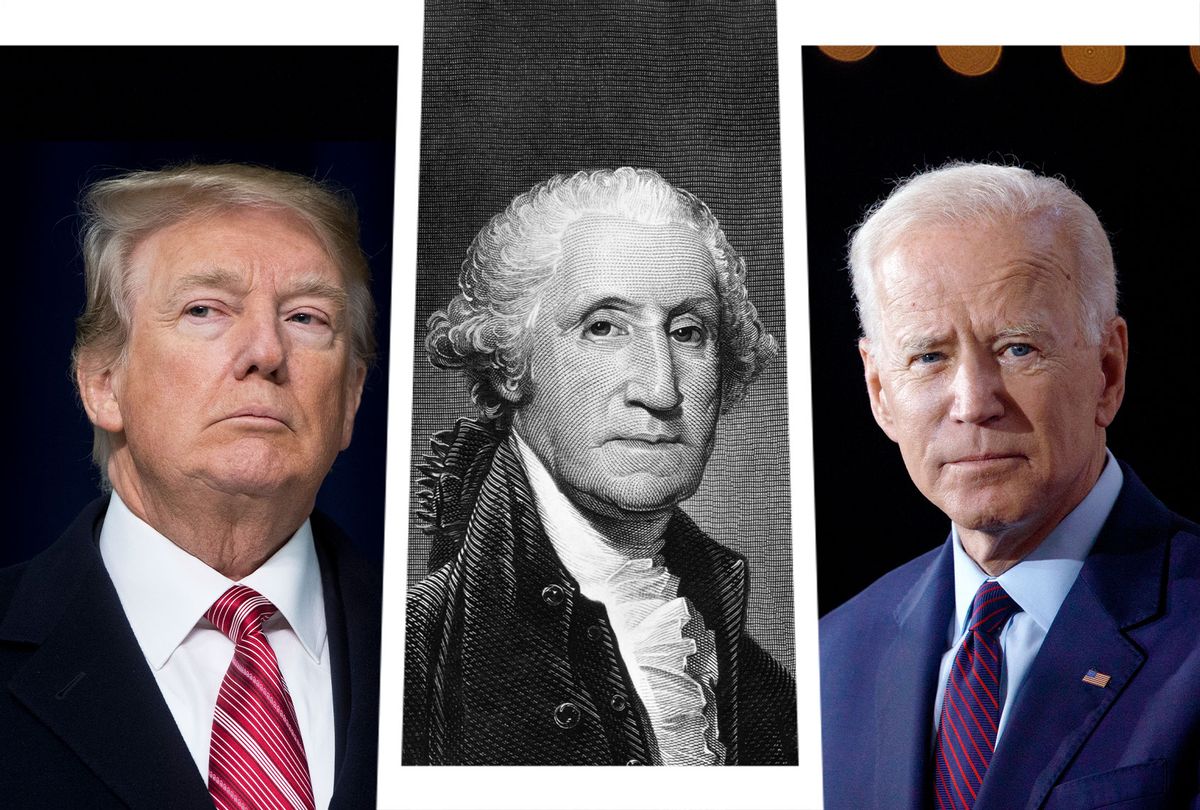

It was the first anniversary of the Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol. Songwriter and playwright Lin-Manuel Miranda had joined the cast of his hit musical "Hamilton" to virtually perform the song "Dear Theodosia" at a congressional event. At a different time on that same day, President Biden delivered a historic speech in which he observed that Donald Trump and his supporters had placed "a dagger at the throat of democracy."

Both moments were powerful reminders of a terrible day in both American history and the larger story of democracy. Yet both also missed an opportunity to use both the day and their platform to remind Americans about one of this country's most important founding documents. Well into the 20th century, it was routinely read by schoolchildren across the land, who were expected to be familiar with its contents.

That document is George Washington's Farewell Address, which was actually the inspiration for the song "One Last Time," from "Hamilton." Its lessons have never been more relevant than since Jan. 6, 2021 — and that can be seen simply by contrasting its language with Biden's.

The common name of Washington's "address" is misleading. Although the ideas were certainly his, Washington essentially co-authored the text with Alexander Hamilton and James Madison over the course of his presidency. He never read it aloud in public, and it was published in a newspaper on Sept. 19, 1796, six months before the end of his presidency. But in another sense the title is entirely fitting, since the Farewell Address became a central part of the first president's legacy.

RELATED: George Washington predicted Donald Trump: Why doesn't everyone know this?

As Washington writes in the introduction, he knew that Americans were concerned about whether democracy would keep on working after he left office. He had served for two terms with a national consensus behind him, but now he was choosing to retire. This meant there would be two tests for American democracy: Washington would have to step down peacefully (which he did), and voters would face the nation's first seriously contested presidential election — between the two men who wanted to succeed Washington, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson.

Washington's message touches on a number of subjects, and there's no use pretending that all of it fits with contemporary liberal or progressive politics. He firmly believed that religion was essential to public morality, for instance, and that it was crucial to balance the federal budget. (Of course, modern-day "conservatives" only pretend to believe in that one.) Other sections of the address are prescient but not specifically relevant to Jan. 6 and its aftermath: Washington's warning that America could become an empire if it gets entangled in overseas military adventures might have changed history if Cold War policymakers had heeded it. There's also a passage on the dangers of regionalism that, though arguably pertinent today, was clearly composed with issues like slavery and 18th-century economic policy in mind.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

But there are also portions of the farewell address that speak clearly to the present moment, in the wake of the 2020 election and the Jan. 6 attack. Take this key passage, in which Washington reflects on the political violence that marked the early days of the American republic. Before this, he discusses how America's original government, as established by the Articles of Confederation, had been too weak. Many people disliked the new Constitution for creating a more centralized state, and that led to serious friction and threats of political violence. Washington understood that democratic governments needed to be accountable, but that didn't mean people could resort to violence over every grievance. He writes:

The basis of our political systems is the right of the people to make and to alter their constitutions of government. But the Constitution which at any time exists, till changed by an explicit and authentic act of the whole people, is sacredly obligatory upon all. The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government.

That's a more eloquent expression of the same thought Joe Biden articulated when he said, much to CNN pundit Chris Cillizza's delight, that "you can't love your country only when you win." He added, "You can't obey the law only when it's convenient. You can't be patriotic when you embrace and enable lies." Those words also echo Washington's from 1796:

All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency.

Washington then transitions to a discourse on partisanship, fretting that factions led by "a small but artful and enterprising minority of the community" might lead a party to take over the nation through manipulative leaders and the support of a zealous minority. That's inconsistent with the true spirit of republican democracy, he argues, which is "the organ of consistent and wholesome plans digested by common counsels and modified by mutual interests." Anti-democratic violence, on the other hand, serves as a potent engine "by which cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people and to usurp for themselves the reins of government, destroying afterwards the very engines which have lifted them to unjust dominion."

This brings us back to Biden, who observed that the Capitol attackers "didn't come here out of patriotism or principle. They came here in rage. Not in service of America, rather in service of one man. Those who incited the mob, the real plotters who were desperate to deny the certification of this election, to defy the will of the voters." He went on to praise those who heroically stood up for democracy, and especially those who lost their lives fighting the right-wing mob.

Washington, to be sure, did not compose the Farewell Address in response to a specific, present-tense provocation. In his most famous passage he elaborates on a possibility that appears to have come true, 220-odd years later — the pressure of extreme partisan division leading to tyranny and autocracy:

The alternate domination of one faction over another, sharpened by the spirit of revenge, natural to party dissension, which in different ages and countries has perpetrated the most horrid enormities, is itself a frightful despotism. But this leads at length to a more formal and permanent despotism. The disorders and miseries which result gradually incline the minds of men to seek security and repose in the absolute power of an individual; and sooner or later the chief of some prevailing faction, more able or more fortunate than his competitors, turns this disposition to the purposes of his own elevation, on the ruins of public liberty.

That seems an entirely reasonable description of Republican plans for the 2024 election, which they clearly intend to win by fair means or foul, including literally overturning the result if their chosen "chief" loses again. Until then, Republicans are largely relying on political paralysis, not out of any genuine conviction but, in Washington's words, "to distract the public councils and enfeeble the public administration." Such a partisan faction, he writes, will use all kinds of underhanded tactics:

It agitates the community with ill-founded jealousies and false alarms, kindles the animosity of one part against another, foments occasionally riot and insurrection. It opens the door to foreign influence and corruption, which finds a facilitated access to the government itself through the channels of party passions.

Presumably Washington feared that American politics at the dawn of the 19th century could be torn between pro-British and pro-French factions. But he was clearly also aware of the the darker possibility that the danger of tyranny could come from within.

More from Matthew Rozsa on the pathways and corridors of American history:

Shares