“It’s a natural instinct to want to find the causes and sources of problems,” says Dr. Lydia Kang. As a practicing physician, Kang understands the value of investigating the origins of illnesses. And as the co-author, with historian Nate Pedersen, of “Patient Zero: A Curious History of the World’s Worst Diseases,” she also recognizes how quickly our curiosity can turn into something far less benevolent.

There’s no more telling contemporary example of collaboration and polarization than the intense, often accusatory response to our current pandemic. In the early days in 2020, coronavirus contagion anxiety and the frantic search for the “ground zero of a new virus,” was quickly weaponized into a rash of anti-Asian hate crimes and racist rhetoric like Trump’s references to “kung flu.” Now, Reddit’s sardonic “Herman Cain Award” sub identifies vaccine skeptics and mask mandate defiers who’ve succumbed to COVID-19 infections. It’s named in honor of the former Republican presidential candidate and face mask refuser, who died a month after attending Trump’s infamous 2020 Tulsa rally. As body counts rise, we seek solutions. We also want names. We want a source. And we want a culprit.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

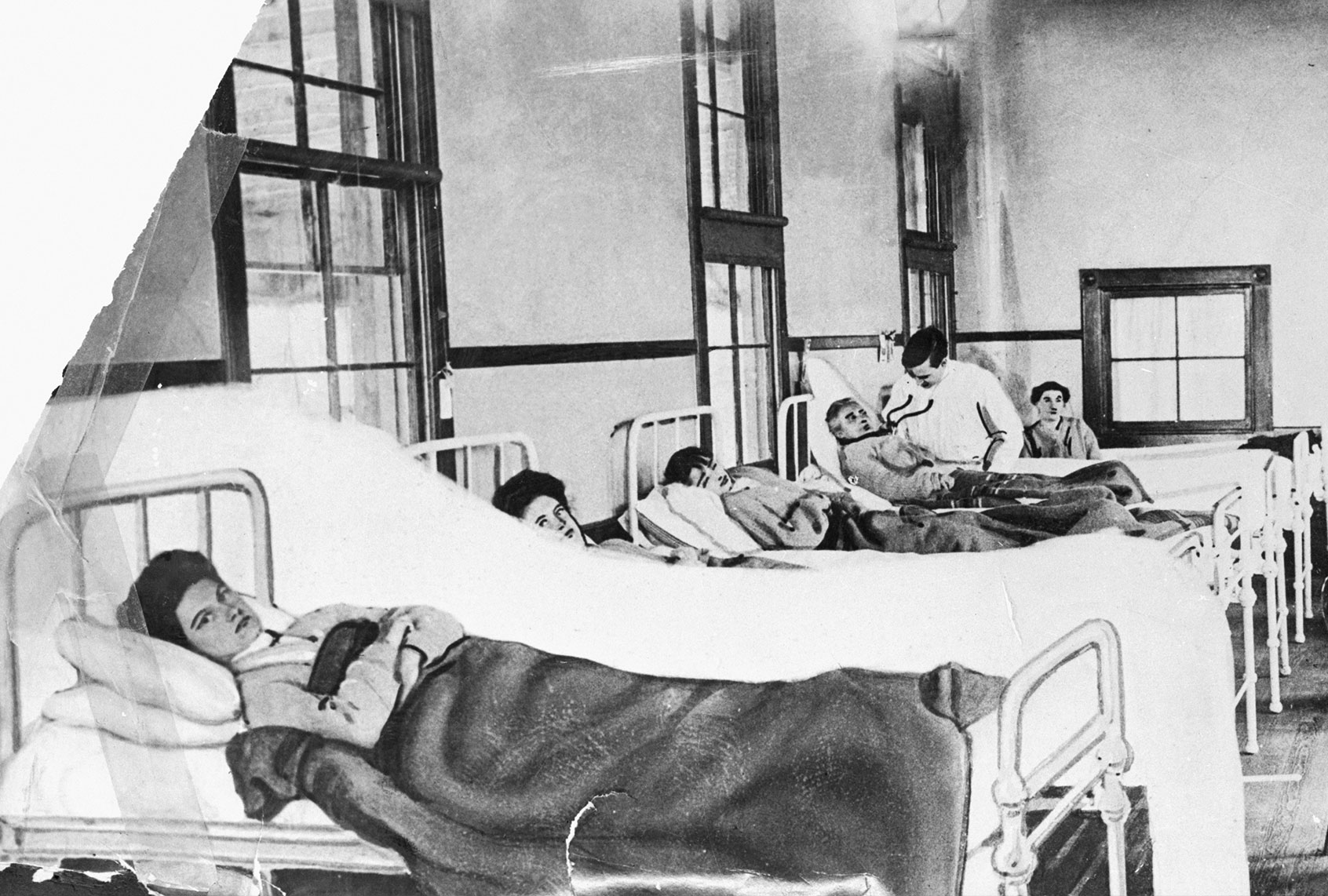

In “Patient Zero,” the authors — whose previous collaboration “Quackery: A Brief History of the Worst Ways to Cure Everything” similarly explored the double edge of good intentions — look at the stages of infection, viral spread and eventual containment through the lens of some of humanity’s most baffling and bedeviling outbreaks. It’s a rich and thought-provoking book, filled with historical photographs, artwork, and unique accounts of patients and researchers grappling for answers in the midst of the most appalling and heartbreaking circumstances imaginable. It’s also a profound reconsideration of our common understanding of our most famous stories of sickness and science. What’s the truth about those notorious “smallpox blankets” European colonizers brought with them to the Americas? Were “Typhoid” Mary Mallon and early HIV patient Gaëtan Dugas really as reckless as their infamy suggests? What are the lessons from how rabies, polio, mad cow disease and the 1918 influenza outbreak were managed that inform our current response to COVID? And when does “a beacon of hope come in the form of poop”?

Salon talked to Kang recently about our endless search for “Patient Zero,” how she and Pedersen found themselves writing about historic pandemics in the midst of a modern one, and what we really need to understand about our outbreak origin stories.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

There is an understandable scientific imperative to trace the origins of viruses and diseases, but in the wider world, that can become a shorthand path to blaming individuals. What have we gotten wrong about “Typhoid Mary,” about Gaëtan Dugas, and about the idea of “Patient Zero” in general?

Whenever we get a cold, we tend to point a finger at a colleague or friend who was sneezing nearby. Something we realized early on was how this book could be construed as a finger-pointing exercise, but we knew it would be far more complex and less blameworthy. If anything, these stories show how layered the issues are, and how we, as an entire species, are responsible for so many new pathogens in this world.

And often, the Patient Zeroes are complicated individuals. Gaëtan Dugas was a multifaceted human being, faulty at times, but generous as well. That is not well construed when many people think of him as the Patient Zero of the HIV and AIDS crisis of the 1980s, which he most certainly is not.

At times, we try to go beyond the first person with the first disease and try to find the spillover event, if there even was one. It was fascinating to find that tuberculosis, for example, has evolved right along with us for thousands upon thousands of years.

This is a book about very real human beings who faced unprecedented medical challenges. It’s very easy — especially now — to feel awash in statistics. What drew you to this topic for your book, and was there a story that particularly affected you?

We were tossing around ideas for a follow-up to “Quackery” in the fall of 2019, and decided on this topic of Patient Zero stories and how epidemics and pandemics unfold. It wasn’t until early 2020 that we realized we’d be writing a pandemic book while living in one.

We each of us had stories we particularly felt drawn to. I was fascinated by prions (and also like to eat cheeseburgers), so the mad cow chapter was absolutely fascinating for me to write and research.

Writing the chapter on the plague (we of course had to write about THE plague of all plagues) was especially hard given the amount of anti-Asian xenophobia that occurred during the outbreak of the plague in Chinatown, San Francisco at the turn of the last century. It was haunting, the echoes of what is happening today with COVID.

You show the speed of innovation in times of crisis. What do you think the ways in which medical mysteries have been approached in the past can teach us about how to better prepare for future ones, and handle our current one?

Technology and medicine are both developing so rapidly that no doubt we will continue to do better in future pandemics than this one. The fact that roll outs for medicine discovery, diagnostic kits, cooperation between nations, and cooperation of the public on a public health levels has been far from ideal shows that we have much to improve upon and learn from. Science dictates that there is nuance in the data, and many parts of the population do not do well with nuance or gray zones. Politics are everywhere, and disparities continue to be severe. So I predict that future pandemics will always have difficulty on various levels as they are discovered and tackled.

You end the book talking about the opposite of the Patient Zero, focusing on the last smallpox patients and the power of progress. Why was it meaningful to tell those stories as well?

We wanted to end by showing how there is hope for the eradication of some diseases, and that though polio, TB, and measles still exist in the world, we have the means to treat and prevent them. Humans are ultimately a hardy species that sets so much of its energy on survival. We are not easily killed, and achieve astonishing milestones in trying to do good things for humanity. Let’s not forget that.

More stories on science and history:

- “Pure America” author Elizabeth Catte sees “the shadow of eugenics on almost everything”

- “Unwell Women” author Elinor Cleghorn: Women’s pain “isn’t taken seriously” by doctors

- Is science stuck? The “Great Stagnation Debate,” explained