This week, nearly 30 days after its launch, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) reached its final destination — a small, gravitational well in space about a million miles from Earth, where it will live for decades or perhaps even all eternity.

“Webb, welcome home!” NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said in a statement Monday. “We’re one step closer to uncovering the mysteries of the universe. And I can’t wait to see Webb’s first new views of the universe this summer!”

The observatory’s permanent home is a stable point in space known as Lagrange Point 2, also referred to as L2. L2 is also a point in space where gravitational forces of the Earth and Sun are in equilibrium, allowing JWST to stay aligned with Earth. L2 will also allow JWST to have a wide, unobstructed view of the universe at any given moment, unlike telescopes closer to Earth (like Hubble) whose point of view is often obscured by the Earth itself.

JWST is a once-in-a-generation space observatory poised to usher in a new chapter for astronomy by peering into distant corners of the universe, surveying the atmospheres of Earth-like exoplanets, and observing more distant stars and galaxies than its predecessors. As the Hubble Space Telescope‘s successor, it is also one of the most expensive space missions (roughly $9.7 billion) in history. In other words, a lot is at stake.

Scientists collectively breathed a sigh of relief when JWST arrived at L2. While the observatory had been tested extensively to ensure that it could survive the vibrations and sound waves associated with launch, it was still a difficult, tense milestone to reach; testing on Earth cannot compare with all that can go wrong in space. JWST also differs from Hubble in that there is no way to fix it in-person should something go wrong; Hubble orbited close enough to Earth as to be able to be serviced by astronauts via the now-retired space shuttle.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

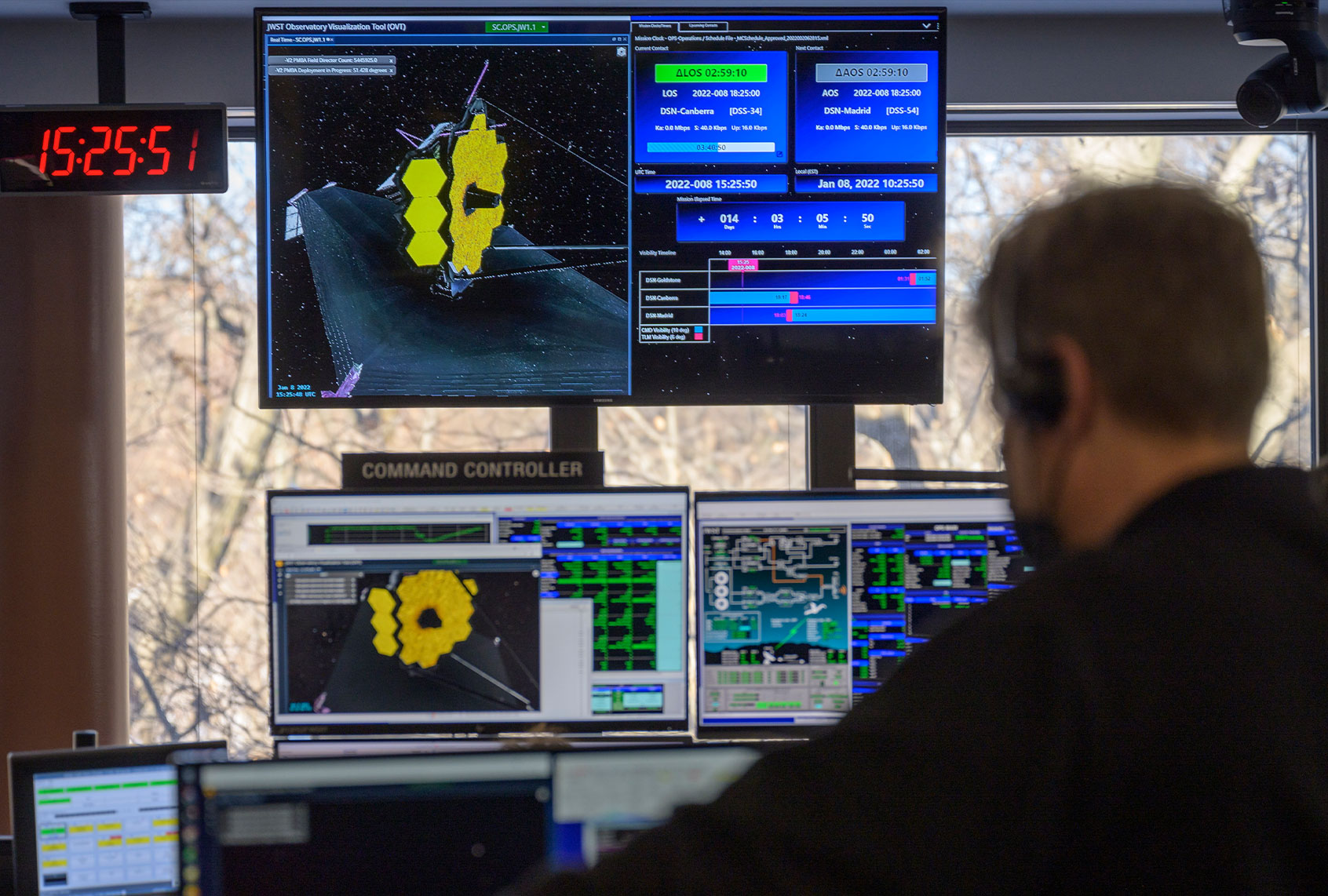

“During the past month, JWST has achieved amazing success and is a tribute to all the folks who spent many years and even decades to ensure mission success,” said Bill Ochs, Webb project manager at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in a statement. “We are now on the verge of aligning the mirrors, instrument activation and commissioning, and the start of wondrous and astonishing discoveries.”

Now that JWST has arrived at its home, is it ready to start collecting data and moving the needle in science? Not yet. There are a few more steps that must come first.

Next, scientists have to give JWST time to quite literally cool down after its long journey to L2. That’s because the observatory’s instruments can only operate at optimal capacity at specific temperatures. As Ochs mentioned, also scientists need to align the primary mirror properly before deploying the instrument package.

RELATED: The Hubble Space Telescope’s weird computer glitch, explained

JWST consists of eighteen 46-pound mirrors, which together form one big mirror (the “primary mirror”), which in total is roughly 21 feet wide. The mirror was built in segments that could fold on top of each other; hence, it will take about two months for those mirrors to unfold and get in their proper, precise positions. The mirrors need to be precise to a length of around 1/5,000th of a human hair to get the most accurate and precise images of the universe.

After mirror unfolding, technicians must align the primary mirror with the secondary mirror, in order to direct the light that JWST collects onto its instruments. After the mirrors are aligned, the equipment will go through rounds of testing.

This means it will be a while before we can see JWST’s first images. Scientists estimate we won’t have those for another five months— around this summer. That is, provided that JWST doesn’t have any malfunctions, which is not guaranteed.

Avi Loeb, the former chair of the astronomy department at Harvard University and author of “Extraterrestrial: The First Sign of Intelligent Life Beyond Earth,” previously told Salon that we won’t know if anything is wrong with the instruments on JWST until it actually starts to observe the sky — which could be a bit problematic.

“Unfortunately, its location at the second Lagrange point at four times the distance to the Moon will not allow us to service it as we did with the Hubble Space Telescope — which is 2,600 times closer,” Loeb said. “The response will depend on the mode of failure; some problems can be partially solved remotely.”

But if the rest of the preparation goes as smoothly as its launch, we should be able to see those spectacular images this summer.

More stories on astronomy:

- Astronomers plan to double-down on the search for extraterrestrial life

- The Hubble Space Telescope’s weird computer glitch, explained

- The once-sedate astronomy world is quarreling over whether ‘Oumuamua was an alien craf