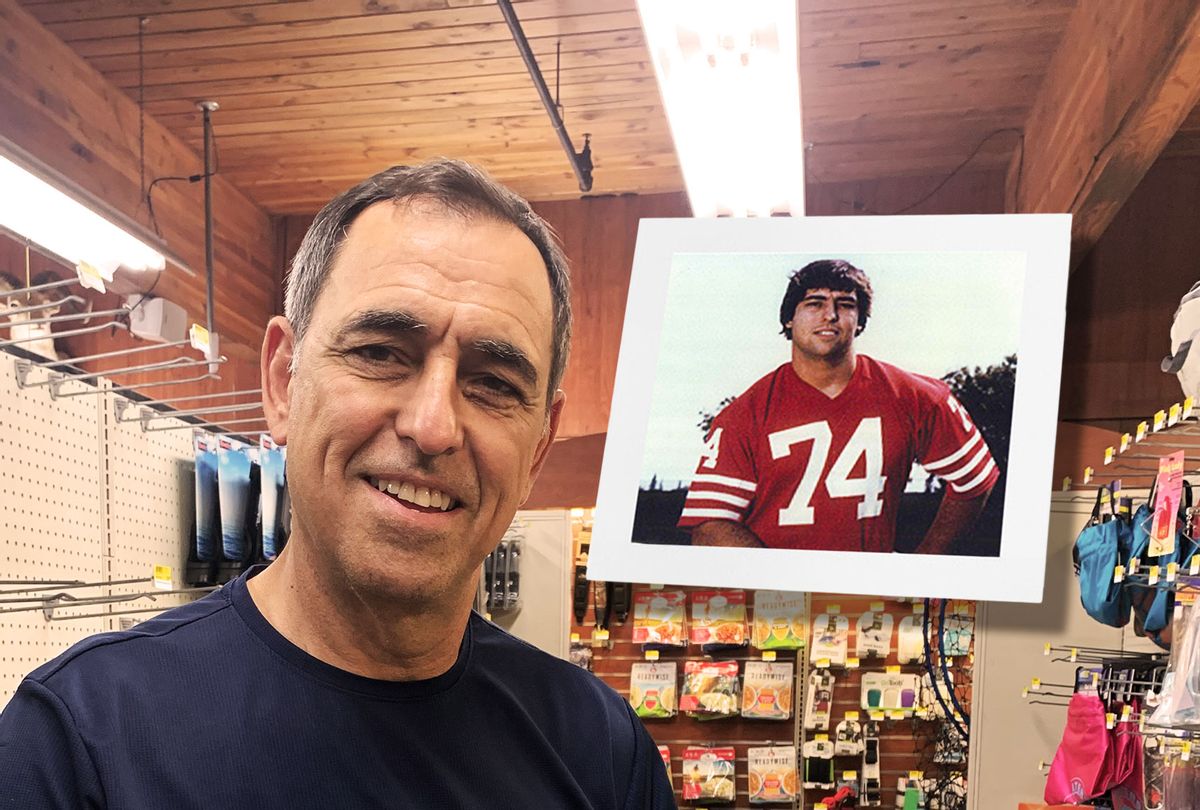

Along with 100 million fellow citizen-spectators, give or take, a 63-year-old former NFL defensive lineman named George Visger will be watching the Super Bowl in two weeks. The San Francisco 49ers, his old team, could be playing in it. (That issue will be decided this weekend in their game against the Los Angeles Rams.)

Visger will be at his new home on the pocket bend of the Sacramento River, five miles south of California's Capitol building. Or maybe he'll take in the big game from the home of his girlfriend Jennifer, a musician and private music teacher in Oakland. Either way, it will be a glorious day.

During his own playing days, Visger was a journeyman, but today he is basking in victory in litigation — which, as we all know, is America's second most popular sport. His view of the Super Bowl, with feet comfortably on the divan, will mark a milestone in an improbable movie-script life, albeit for the most painful reasons.

A glorious day — if you ignore the fact that Visger will have to refer to the noodlings in his Rite-in-the-Rain notebook at the start of the third quarter to remind himself which team was leading at halftime (or about pretty much anything else that happened earlier that day). His stash of waterproof notepads is a remnant of his stop-and-start career as a wildlife biologist, which often entailed consulting on the construction and management of wetlands and mitigation banks as part of building projects. In the best times over the course of his struggle to make himself whole again post-football, he had his own company in this field.

Christopher Nolan's 2000 film "Memento" is a thriller about a man who suffers a traumatic brain injury. Piecing together information about the incident in which his wife was murdered and he was injured, he has to process things backward, sideways, diagonally or in a loop — any way but in linear fashion, since his short-term memory is shot.

RELATED: Everything you wanted to know about "Memento"

Meet George Visger, your real-life "Memento" guy. Don't try taking away his notepad and expecting him to know where he just parked his truck.

He's a poster boy — one of tens or hundreds of thousands across the country, professional and amateur alike — for the proposition that football players are the Roman gladiators of late-empire America. This observation is no less accurate for being a cliché. Thanks to the addition of a 17th regular season NFL game, Super Bowl Sunday now rolls within a week of President's Day weekend, that quaint civics lesson turned department store sale-a-thon, long ago eclipsed as our true national winter holiday by a hyped-to-the-gills sporting spectacle. In the year just concluded, NFL TV ratings surged back to their highest levels since 2015.

Even before the pandemic and the Great Resignation, enough hungover workers have been calling in sick on the Monday morning after the Super Bowl to render the combined pregame, game and postgame a de facto three-day weekend. There is disputed data to suggest an uptick of incidents of domestic violence surrounding this gathering at the national hearth of TV and streaming device screens. Many will have one eye on the action and the other on the real action: universal, legal and suddenly de-stigmatized opportunities to bet on everything from which team covers the "spread" to which pass receiver garners the most "targets."

As a kid in Stockton, California, and then as a young adult, George Visger was addicted to the cathartic, manly-man thwak of shoulder pad on shoulder pad (or worse). The price he paid was cumulative brain trauma, both concussive and sub-concussive. In 1980 the New York Jets made him their sixth round draft choice and signed him for a $15,000 bonus. After they cut him at the end of training camp, the 49ers picked him up, and he took snaps in several games for a legendary team that the next year would win the first of its five Super Bowl championships.

Visger's very first regular season game, against the Dallas Cowboys, left immediate cranial handprints. On two different trap plays, the Dallas tight ends — Doug Cosbie on one play, Jay Saldi on the other — blocked for the ball carrier by whacking Visger on the earhole of his helmet. The second shot knocked him out. The trainers administered smelling salts and the head coach, Bill Walsh, sent him right back in; Visger didn't miss a play. Today he points out that Walsh is regarded in NFL lore as a legend and a genius: "Maybe he was a genius in more ways than one. He stuck me with over $100,000 in medical bills over five years."

RELATED: Football's unknown epidemic: When Black players die suddenly, the cover-up begins

Four decades and nine brain surgeries later, Visger has finally won at the game of life. First, in 2016, the NFL came to a federal appellate court settlement of a case known as "In re: National Football League Players Concussion Injury Litigation." The league continues to fulfill claims on a rolling basis. The total payout to claimants currently stands north of $800 million.

Visger was named plaintiff No. 22 on the list of the more than 120 NFL alums in that mass action. After the attorneys' cut, his check was fairly modest. He hasn't told me the amount, but I calculate that the ceiling is in the mid-six figures, a pittance relative to his 38 years of havoc and hell.

The first factor working against Visger in the settlement tiers is straightforward: He hasn't died. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — the catch-all named condition of brain deterioration, marked by tangled accumulations of tau proteins — is still only detectable postmortem. Nor has Visger been diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's Disease or Alzheimer's or Parkinson's.

For purposes of the NFL lawsuit, therefore, he was classified as "Neuro Cognitive Impairment 2.0," which pays up to $3 million for those with five years of active service. Visger was credited for one year of service, but not for his second season in the NFL, when he was injured in preseason and underwent three brain surgeries. (The average NFL playing career is 3.2 years. It takes four years to be vested in the Bert Bell/Pete Rozelle NFL Retirement Plan, which is named for the league commissioners who successively presided over its television explosion in the late 1950s and '60s.)

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

What Neuro Cognitive Impairment 2.0 means, in Visger's case, is that an image of his brain shows the most grotesque caverns and crevasses.

Much more significant for Visger than the NFL settlement was his ultimate success in tortuous, marathon worker's comp litigation against Travelers Insurance. Last year, under prodding by a state court judge in Southern California, that case reached a comprehensive settlement. That amount is confidential, too, but is surely many times what he got from the NFL.

Visger got a minority of the funds upfront, with the rest parceled out over time under the guidance of a financial adviser. Several years earlier, he had completed an amicable divorce with his wife, Kristi, whom he met 25 years ago; they would become teaching colleagues at Sacramento's Hiram Johnson High School. Though he terrified her at times with anger management issues and lack of impulse control, and they haven't been together for years, there was never an estrangement of the heart. Their daughter Amanda, 24, and son Jack, 22, have new cars and funding for higher education. George, Kristi and their kids are all set up with health care plans, courtesy of the settlement. (More later on Stefani, Kristi's daughter from a previous relationship, whom George helped raise.)

And there's that house near the riverbank, in reach of Visger's favorite fishing and hunting spots.

The insurance company's end-game legal tactics included trying to slap a lien against Visger for his NFL settlement check. By then, he was well versed in the ways of cutthroat lawyers. He had already been schooled in the ways of cutthroat football. There were iterations of malpractice claims against 49ers team doctors; submissions to the NFL retirement fund that went nowhere, because Visger wasn't vested; the reality check of statutes of limitations; the imbalance of legal firepower between his modest teams of earnest disability lawyers and the paperwork factories and deep, deep pockets of corporate football.

"My life story," Visger says, "has been either science fiction or comedy. Take your pick."

* * *

I met Visger in 2012 at the Hyperbaric Oxygen Clinic in Sacramento. The short answer as to what brought us together is that my work writing about the less-scrutinized angles of football harm has put me in touch with many ex-players. Many of their stories were unimaginably dark — filled with heartbreaking anecdotes of interludes of crazy behavior, broken relationships, financial ruin. I came to believe these added up to far more than the wan "What price glory?" tropes of mainstream media. They go down to the very bowels of American culture and the unaccounted, and unacceptable, human costs of the secular religion that is football.

Among all those damaged men, Visger's narrative resonated the most in its exotic details. Also, he was the most charismatic of narrators.

RELATED: Troubled waters: USA Swimming's struggle to cover up its sexual abuse crisis

That day in Sacramento, he was trying to work through solutions found on the fringes of conventional medical advice. In 2010, the psychiatrist and brain disorder specialist Dr. Daniel Amen directed him to the benefits of hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT), which involved immersing himself for 75-minute sessions in a chamber of compressed pure oxygen. These sessions seemed to clear his mind somewhat from the side effects of a cocktail of medications, which included at various times Dilantin, Depacote, Phenobarbital, Kepra and Zonegran (for seizures); Lamictal (for seizures and bipolar disorder); and Aricept, Risperdal and Namenda (for dementia). Visger has had a total of 232 HBOT sessions. At the time of our first contact, they were almost daily.

One of the best parts was that the co-owner and manager of the clinic, Mike Greenhalgh, let Visger sleep on the floor at night and use a side cubicle as his office during the day. This was during Visger's hardcore near-homeless phase, when he was putting his head down on a pillow at a Motel 6, if he could afford it, or in a trailer on a brother's property, if he couldn't. In 2011, George and Kristi had lost their house in Grass Valley, in the gold country on the way to Lake Tahoe.

Even in the face of such adversity, George cut an almost incongruously positive and affable figure in person, whether it was in Sacramento or in my own neck of the woods, the San Francisco Bay Area, when he crashed with an old friend there. For several years I would drive up to see him during the holidays so we could go out to dinner. One year he told me to meet him at the address of an apartment complex rather than Greenhalgh's clinic. The place turned out to belong to his new girlfriend, a middle manager for a Big Pharma company who had once been married to an NFL running back who one year led the league in rushing yardage. The three of us went out together.

In the words of that 1930s Tin Pan Alley song, "Ya gotta be a football hero/ To get along with the beautiful girls …"

Over dinner, George would tell the same stories over and over, then apologize for forgetting that he'd already told them to me many times before. The one whose repetition I especially didn't mind was about bonding and falling in love with Kristi while they worked together at Hiram Johnson, one of Sacramento's toughest inner-city schools.

Kristi was the type of teacher who left the door of her classroom open during lunch: She knew fights would break out on the school grounds, and some kids didn't feel safe. Up to 20 of them regularly ate lunch in Kristi's room. Before heading out to school every morning, she had George prepare extra bags for the food-insecure among them.

But what really sealed the deal for George was Kristi's beautiful two-year-old daughter, Stef. "I fell in love with two girls at once," he says. At 38, he became an instant stepdad.

Even today, it's not hard to figure out his way with the ladies. Minus his football weight, the 6'5" George is rangy and graceful. (OK, there was that one time when he fell while doing work on the roof of the house in Grass Valley, sustaining … a concussion.) He laughs loudly and often. His intense eyes, which maintain contact, are framed by beetle brows. He owes his Mediterranean dark good looks to his beloved mother, the 5'1" "Big Rita," who died at age 94 in 2018.

Rita grew up over her Lebanese parents' corner store in downtown Stockton. The man she married, Jack, had been a 17-year-old gunner on a Navy troop transport vessel in the South Pacific during World War II. Driving a beer truck, he earned enough to buy a three-bedroom house with no air conditioning — quite the challenge for raising three boys and three girls in a Central Valley town where the thermometer can often hit 110 in the summer. George was the fifth of the six kids. Jack died of cancer in 1999, at age 72.

George's football indoctrination came at age 11 with the local Pop Warner league's West Stockton Bear Cubs, who made it all the way to the Junior Redwood Bowl in Eureka, more than 300 miles away on the Northern California coast. A less-than-fond memory was the coach's introduction of a sick drill called "Bull in the Ring," which was likely the cause of Visger's earliest concussion and which at least some football people now acknowledge is barbaric. Two other kids from the Bear Cubs would also go on to the NFL: center Jack Cosgrove, an eighth-round draft choice of the Seattle Seahawks, and tight end Pat Bowe, who made the Green Bay Packers as a free agent. Visger also had a Little League baseball teammate, Von Hayes, who became a star with the Philadelphia Phillies.

Visger was All-Northern Californian and a top 100 All-American at the iconically — and ironically — named Amos Alonzo Stagg High School. One of the founding fathers of modern football coaching, mostly from decades at the University of Chicago, Stagg finished his career at College of the Pacific and Stockton Junior College, before his death in 1965.

Heavily recruited by college football programs, Visger chose the University of Colorado, where he majored in fisheries biology. From a young age, he was a Jacques Cousteau wannabe as well as a jock. Visger's Golden Buffaloes played in the 1977 Orange Bowl. One teammate, Leon White, became Vader, a famous pro wrestler in both the U.S. and Japan.

* * *

At the Jets' spring mini-camp in 1980, Visger bench-pressed 430 pounds and squatted 500-plus. He had a 28-inch vertical jump and ran a 4.9-second 40-yard dash, and his body fat was 18%. But the defensive line coach took him aside and said he needed to bulk up by an additional 25 pounds, to 275. A marginal teammate whom all the players called Dr. D (for dirt) found a way to get them steroid connections. In Visger's case, the regimen was 20 ml of Dianobol, 15 ml of Deca-Durabolin and 10 ml of Anavar. Visger reported to summer training camp at 275 pounds, with a 32-inch vertical jump and bench-pressing 460. But it wasn't good enough. To give you an idea, the Jets' best defensive lineman of that period, Mark Gastineau, weighed 282 pounds, had 9% body fat and ran the 40 in 4.4 seconds.

On the 49ers a year later, Visger found himself besieged with pulsating headaches, marked by projectile vomiting, bright lights in his peripheral vision and intermittent hearing loss. The 49ers' orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Fred Behling, prescribed medication for high blood pressure. The only palpable effect from that was that, at night, Visger's right arm curled up to his armpit, as if he were paralyzed or had palsy.

When Visger confronted Behling at the team facility, the doctor finally agreed that this wasn't hypertension. His patient's brain was hemorrhaging. Behling scribbled down the name and number of another doctor, and told Visger to lie down for a while, then drive himself to the doctor.

RELATED: Dead in the water: The tragic human cost of swimming's abuse scandals

Upon examining Visger, this second doctor booked him promptly for emergency surgery. He had hydrocephalus, "water on the brain." A ventricular-peritoneal shunt was permanently installed in his brain. A hole was drilled in his skull to allow a perforated catheter to pass into the ventricles in the middle of his brain. The catheter ran to a pressure valve installed in the back of his head; from there, a tube ran into his abdomen to drain excess spinal fluid.

Over a 14-day period before and after his 23rd birthday, Visger was in intensive care at Stanford Hospital. Bill Walsh's secretary called once to see how he was doing. Walsh's story to the team was that Visger was recuperating at his parents' home in Stockton following a "spinal test." Visger's apartment roommates, veteran linebacker Terry Tautolo and rookie running back Scott Stauch, visited him at the hospital. Walsh cut them from the squad the same week.

The team's trainers told Visger they were looking into rigging some kind of customized helmet, which would protect his brain shunt and allow him to continue bonking heads at the line of scrimmage. "I was all in," Visger says. When he returned to the team facility with 45 staples at the back of his head, none of the other players knew he'd had brain surgery. They thought he'd simply been released.

At the 49ers' practice facility, then in the San Francisco suburb of Redwood City, Visger picked up where he'd left off: He attended team meetings and continued rehabbing a separate knee injury (for which he has had three other surgeries, the first of them that year). One day, while working out in the weight room, he met general manager John McVay (whose son, Sean, is now head coach of the Los Angeles Rams — who play the 49ers this weekend for a Super Bowl berth), who was there on a tour with business friends and dignitaries. McVay introduced him as a defensive lineman who was on injured reserve following two knee operations. A woman in the tour group asked Visger how that had happened: two procedures on the same knee? He started to explain that there was also a brain operation involved, but McVay shut down the conversation.

In May 1982, four months after the 49ers won Super Bowl XVI, Visger's brain shunt failed while he was fishing in Mexico with one of his brothers, who had to bring George home in a coma. There followed his second and third brain surgeries, 10 hours apart. Visger was given last rites following each one. When he recovered, he was handed a pile of hospital bills.

In the mid-'80s, Visger successfully managed what may have been the first California worker's comp claim by an NFL player. The 49ers were required to underwrite vocational rehabilitation. He put in five years completing his studies in wildlife biology at Sacramento State University, while also earning a general contractor's license. He persisted through four more brain surgeries in 1987 and '88; after the last one, he left the hospital in 23 hours and was back in organic chemistry class the next day.

What happens when a shunt fails is that Visger lapses into a coma and will die within a day or so, without surgical intervention. The human body's production of spinal fluid, about a pint per day, flows into ventricles in the middle brain. In Visger's case, that fluid gets blocked by scar tissue formed through serial concussions.

"My brain starts getting crushed," he says. "The feeling is like having a beer can crushed in the middle of your brain."

Visger has worked on one brother's construction gang, taught classes, conducted protocol surveys on threatened and endangered wildlife and spoken at numerous brain injury conferences. In 2012, the California State Senate honored Visger and his former 49er teammate Dan Bunz during Brain Injury Awareness Month. Bunz was the linebacker who stuffed the Cincinnati Bengals' huge fullback, Pete Johnson, to cap the goal-line stand that saved San Francisco's first Super Bowl win.

* * *

There's a cool school of analysis of the nexus between football and America's rickety public health that's inclined to resist the conclusion that we are all George Visger. Packers' quarterback Aaron Rodgers may be an anti-vax jerk, but he was also short-listed for permanent host of "Jeopardy!" Tom Brady has not strangled his supermodel wife, Gisele Bündchen, on the 50-yard line in the middle of the Weeknd's halftime show.

But intelligent fans are also familiar by now with pieces of the mountains of evidence to the contrary. They are found on police blotters, in TMZ reports and on the back pages of those newspapers that still bother to publish wire-service items about the premature and grisly deaths of former players, whether celebrated or obscure.

We also realize, somewhere deep in our medulla oblongatas, that no single headline-friendly metric, such as the number of athletes who die young after taking risks to become rich and famous, can capture the full societal cost of football. For starters, our football problem isn't just about the few hundred men a year who rise to the elite gladiator caste of the NFL. Social pressure on young males from their earliest ages pushes them into the feeder systems of (in descending order) college, high school and pee-wee programs. In 2014, Paul Bright Jr., the 24-year-old son of Kimberly Archie, who has become an anti-football activist and litigation consultant, died in a motorcycle accident after years of irrational behavior. A brain autopsy confirmed that Bright had CTE, even though his football career ended in high school.

Nor is the issue of football's overall harm only about death. The sport has wormed its way far enough into the bone marrow and psyche of enough men to inflict quality-of-life damage. With careful inspection, like that given to carcinogenic additives to processed foods, that damage can be found in rates of violent crime, substance abuse, domestic abuse, declines in workplace productivity and satisfaction. In all likelihood, given the popularity of the sport and the human capacity for denial, these factors won't get seriously measured for centuries — perhaps by future or alien archeologists tasked with assessing "the decline and fall of the American empire."

In the meantime, we hear the stories, at least some of them, even if we aren't fully prepared to process them.

We hear about Travis Williams, "the Road Runner," who set kickoff return records for Vince Lombardi's last championship team before dying, drug-addicted, on the streets of Richmond, California. He was 45.

We hear about David Woodley, quarterback on the losing 1983 Super Bowl Miami Dolphins, who was finished at 30, descended into alcoholism, had a liver transplant at 33 and died at 44.

We hear about another quarterback, Mark Rypien, who was MVP of the 1992 Super Bowl for the Washington football team, whose mental health struggles have encompassed a suicide attempt and a charge of domestic violence.

That's before we get to the most dramatic examples, such as the suicides by gun of the former defensive superstars Dave Duerson (at age 50, in 2011) and Junior Seau (at age 43, in 2012).

In the last year alone, we have heard about former San Diego Charger and Tampa Bay Buccaneer Vincent Jackson, dead in a Florida hotel room of "chronic alcohol use," at 38. In the still-active or sort-of-active ranks, we have heard about the recent sagas of star defensive back Richard Sherman and star receiver Antonio Brown. Sherman's erratic behavior during the last offseason resulted in charges of burglary, domestic violence, resisting arrest and fleeing the scene. After those charges were dismissed, Tampa Bay cheerfully snatched him up to fortify their defensive secondary.

Brown's one-year-plus employment by the Buccaneers involved multiple accusations of sexual assault and falsified COVID vaccination records, even before he contributed to the history of the Great Resignation by tearing off his jersey, midway through a game, and departing the stadium bare-chested. He paused to wave to the crowd and perform jumping jacks in the end zone, before claiming that his dispute with the coaches was over an ankle injury. Was that evidence of CTE? Or just too much football?

Like so many of the sport's casualties, George Visger is not ideological about football's future. But he says to list him among those who are highly skeptical that "reform" is possible.

You want to change the culture, he asks rhetorically? "Fine. Then remove helmets. All helmets do — especially the new and improved ones — is add a false sense of security. From what's happened to me, I know most of all that a brain injury is like throwing a rock in a pond. The ripple effect, the overall number of people impacted, is huge. It destroys quality of life — not just the immediate victims', but also those around them. No game or amount of money is worth that kind of price. Yet that is exactly the price that continues to get paid, many times a year, all across our land."

Shares