Years ago, a prominent Black psychologist told me that racists almost always tell on themselves. That advice has proven very useful in my life. That tendency — if not compulsion — to reveal their racist beliefs and values is especially powerful for the affluent, the influential and others with a public voice.

You just have to know to listen. Sometimes the reveal is obvious, and at other times it is subtle. But they almost always tell on themselves.

Why? This is likely a function of hubris and arrogance, along with a deeply held belief that people like them will not be held responsible for their behavior. They also believe that most other white people agree with them, albeit if in secret, but are constrained by politeness or “political correctness.” In essence, they think white racists are America’s real “silent majority,” and moreover that white people are the most authentic and “real” Americans. Black people and other nonwhites are something else, something second class or less than — they are diminished Americans at best, in various ways, inauthentic or suspect.

Such a belief about the inferiority of nonwhites, at least until proven otherwise to the satisfaction of the white gaze, is a type of background noise constantly present between the beats of so much of American life and history.

RELATED: Biden must make clear what Republicans know: The fight for democracy is a struggle over racism

Last week, in response to a reporter’s question about the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act, Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said: “If you look at the statistics, African American voters are voting in just as high a percentage as Americans.”

Later that day, on Jan. 20 — the one-year anniversary of Joe Biden’s inauguration — Senate Republicans refused even to allow a vote on the bill named for the legendary civil rights leader, which would help ensure that the voting rights of all Americans are protected.

The meaning of those words was clear enough, no matter how McConnell sought to spin them afterward. The Republican leader in the U.S. Senate was saying that Black people are not exactly “Americans,” as compared, quite obviously, to white people.

Contrary to what some would prefer like to claim, this was not a gaffe or a clumsy misstatement. McConnell spoke his personal truth. As powerful white men so often do, he told on himself. Indeed, why should this surprise anyone? McConnell has shown through his behavior and words, and more importantly through the public policies and laws he has supported and advanced, that these are his deeply held and sincere beliefs.

McConnell supports a new Jim Crow apartheid system, where Black and brown people’s votes — and by implication their other civil rights and human rights — are to be restricted and suppressed, through voter exclusion, gerrymandering, changes to election rules and other means both legal and otherwise, including violence, intimidation and, if need be, a coup against democracy such as the one we experienced last January.

Mitch McConnell remains a leading figure in the Republican Party — in legislative terms, perhaps its most powerful figure — which can now be considered the world’s largest white supremacist organization. The fact that McConnell personally dislikes Donald Trump is, in this context, largely irrelevant. He supported Trump’s fascist agenda without complaint for four years, advancing it through Congress as far as possible.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

This should be obvious but still needs to be said: McConnell’s implicit belief that Black Americans are not full-fledged “Americans” is absurd on many levels. It is based on the premise that Black people remain guests or provisional residents in a country they literally built through centuries of violence, enslavement, murder, rape and other forms of exploitation. In so many ways, America would not exist as it is today without the labor, suffering, survival, intelligence, creativity and strength of Black people.

Ralph Ellison addressed this in his famous essay, “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks“:

The fantasy of an America free of Blacks is at least as old as the dream of creating a truly democratic society. While we are aware that there is something inescapably tragic about the cost of achieving our democratic ideals, we keep such tragic awareness segregated in the rear of our minds. We allow it to come to the fore only during moments of great national crisis.

On the other hand, there is something so embarrassingly absurd about the notion of purging the nation of Blacks that it seems hardly a product of thought at all. It is more like a primitive reflex, a throw-back to the dim past of tribal experience, which we rationalize and try to make respectable by dressing it up in the gaudy and highly questionable trappings of what we call the “concept of race.” Yet despite its absurdity, the fantasy of a Blackless America continues to turn up. It is a fantasy born not merely of racism but of petulance, exasperation and moral fatigue. It is like a boil bursting forth from impurities in the bloodstream of democracy….

Materially, psychologically and culturally, part of the nation’s heritage is Negro American, and whatever it becomes will be shaped in part by the Negro’s presence. Which is fortunate, for today it is the Black American who puts pressure upon the nation to live up to its ideals. It is he who gives creative tension to our struggle for justice and for the elimination of those factors, social and psychological, which make for slums and shaky suburban communities. It is he who insists that we purify the American language by demanding that there be a closer correlation between the meaning of words and reality, between ideal and conduct, between our assertions and our actions. Without the Black American, something irrepressibly hopeful and creative would go out of the American spirit, and the nation might well succumb to the moral slobbism that has always threatened its existence from within.

In many ways, the Black Freedom Struggle was (and is) an attempt to save America from its own worst impulses — from racism and white supremacy, but also from greed and selfishness and widespread inequality and other anti-democratic and anti-human forces.

Consider one of recent history’s great what-ifs: Would America now face its current crisis of democracy — and so many other disasters, both day-to-day and existential — if Black America’s warnings about Trump, the Republican Party and the larger white right had been heeded in 2016? How much misery, death, destruction, sorrow, pain and loss, both already here and soon to come, could have been avoided?

Mitch McConnell has no such awareness. But with his clear pronouncement that “African American voters” are in some unspecific way not “Americans,” he was summoning up from the worst parts of the country’s history — like a dark priest calling up a Lovecraftian horror — a question that has remained unanswered for centuries.

Are Black Americans full and equal citizens and members of this nation and this society, on the same level as white Americans? Should all Americans, irrespective of race or color, be equal in their constitutionally guaranteed rights and liberties? Does “We the People” include white people and nonwhite people on an equal footing?

RELATED: Are Democrats the “real racists”? Well, they used to be: Here’s the history

These questions, and how they should be answered, are the driving force behind the rise of Trumpism and American neofascism, and the subsequent assault on America’s multiracial democracy. McConnell’s straightforward statement that Black people are somehow distinct from “Americans” does not reflect an isolated or anachronistic belief, but rather one widely held across white America.

Public opinion and other research has repeatedly demonstrated that being “American” is conflated with being “white.” Social scientists and other experts have also shown that white Americans believe themselves to be more patriotic and more loyal, and to possess more quintessential “American values,” such as hard work, “personal responsibility,” individualism and discipline, than Black Americans.

Other research shows that the political (and other) decision-making of many white Americans, especially conservative authoritarians and Trumpists, is highly motivated by social dominance behavior and a desire to protect and expand the power of white people in American society. A significant percentage of white Americans — especially those who identify with the Republican Party or who support Trump — are willing to abandon democracy if it means sharing equal power with Black and brown Americans.

New research also shows that tens of millions of white Americans are willing to condone or endorse violence to remove Joe Biden and the Democrats from power, in defense of the “American way of life” and “traditional values,” thinly veiled code phrases for white power and white privilege. Those are the same people who are likely to support last January’s attempted coup and the assault on the U.S. Capitol.

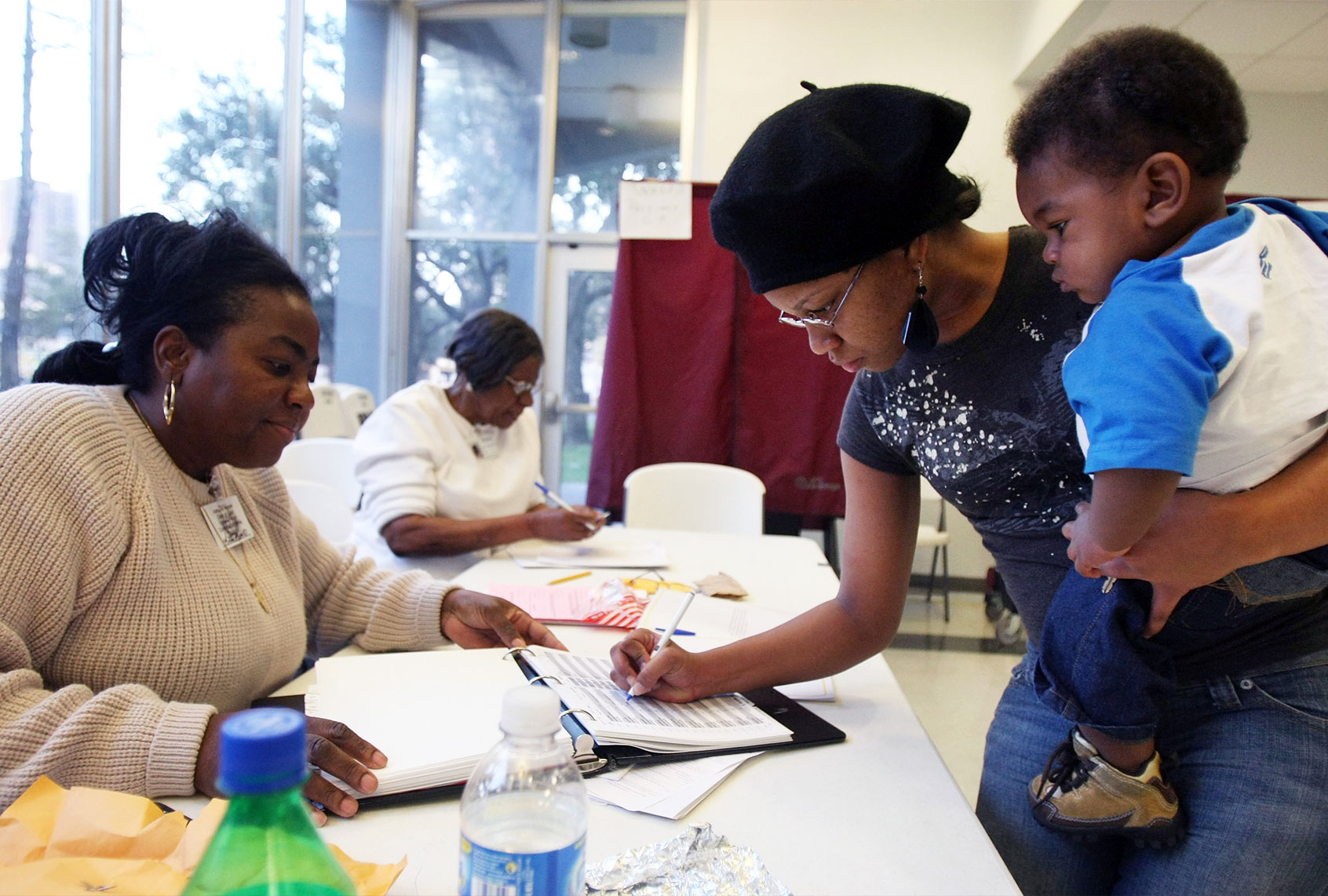

In response to McConnell’s remarks, many Black Americans took to social media and elsewhere to assert their dignity, humanity, and full American belonging. Many Black women and Black men donned their military uniforms as they channeled the power of the “Double V” campaign during World War II and Black Americans’ centuries of military service and patriotism as a way of battling against white supremacy in its many forms. That Black Americans feel the need to do this all over again in the 21st century is an indictment of America’s lack of progress along the color line.

In January of 1942, a man named James G. Thompson wrote a letter to the Pittsburgh Courier, a prominent African-American newspaper. In that letter, he tried to work through the complex and conflicted feelings many Black Americans had about World War II, America and the conundrum of military service:

Being an American of dark complexion and some 26 years, these questions flash through my mind: Should I sacrifice my life to live half American? Will things be better for the next generation in the peace to follow? Would it be demanding too much to demand full citizenship rights in exchange for the sacrificing of my life? Is the kind of America I know worth defending? Will America be a true and pure democracy after the war? Will Colored Americans suffer still the indignities that have been heaped upon them in the past? These and other questions need answering; I want to know, and I believe every colored American, who is thinking, wants to know. …

The V for victory sign is being displayed prominently in all so–called democratic countries which are fighting for victory over aggression, slavery, and tyranny. If this V sign means that to those now engaged in this great conflict, then let we colored Americans adopt the double V V for a double victory. The first V for victory over our enemies from without, the second V for victory over our enemies from within. For surely those who perpetrate these ugly prejudices here are seeking to destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.

Thompson’s letter still resonates; it offers more evidence of how America’s history, for good and for ill, echoes through to the present. This is especially true in the Age of Trump, a moment when America’s neofascist tide is rising and so many in white America still doubt that Black and brown people should have the same equal and full rights as white people.

Mitch McConnell’s beliefs about who is a “real” American, and who is not, took vivid and monstrous human form last Jan. 6. Trumpists waved the Confederate flag, one of America’s and the world’s most potent symbols of white supremacy, as they attacked the Capitol. They assembled a working gallows: In America, such imagery cannot be separated from the lynching of thousands of Black men, women, and children during the Jim and Jane Crow terror regime. Trumpists carried a huge Christian cross through the crowd, a symbol of the way white supremacy and “White Christianity” are inseparable bedfellows in America’s history.

Trump’s attack force was willing to kill and die for that cause of ending multiracial democracy and their collective belief, stated or otherwise, that white people like them have a special claim on the status of “American.”

Black and brown Capitol police officers (and their white comrades) fought back against these thousands of rage-filled Trump attackers to defend the Capitol and the people in it — and multiracial democracy itself. Many of those law enforcement officers were assaulted with racial slurs and other white supremacist invective. After Trump’s attack force had finally been driven from the Capitol, it was Black and brown janitors and other maintenance people who put things back together again, cleaning up feces, urine, litter and other evidence of vandalism and hooliganism.

Beyond his beliefs about who the real “Americans” are, Mitch McConnell’s comment was incorrect in another sense as well. As the Washington Post explained:

McConnell not only overstated the situation a bit, but comparing the turnout of Black voters to the entire voting population is misleading because these numbers are apples and oranges — the entire population (in which the turnout rate is dragged down by other ethnic groups) versus just one ethnic group. The more appropriate comparison is between ethnic groups, such as White Americans and Black Americans. That comparison shows there has been a persistent gap — and it increased in 2020.

But even to vote in the numbers they did, Black Americans had to overcome numerous roadblocks and obstacles put in place by the Republican Party and its agents. In response, McConnell and his allies and supporters have made clear that they believe Black Americans (and other nonwhites) must work much harder still, even to have the hypothetical chance of exercising their constitutionally-guaranteed rights and liberties on an equal basis with white Americans.

In America, white privilege and white power remain normalized and idealized, and rich white men — especially if “Christian” and “conservative” — are understood to be the natural and rightful rulers. White America will not surrender such a vision, and such entrenched power, without a struggle. The psychological and material wages of that idea of whiteness are too great. Far too many are willing to kill and die for it.

More from Salon on the renewed rise of white supremacy:

- Right’s cynical attack on “critical race theory”: Old racist poison in a new bottle

- Who were the Jan. 6 attackers? Isolated white folks, searching for meaning — and enemies

- Imagine another America: One where Black or brown people had attacked the Capitol