While it's morally repellent and legally inadvisable, there is nonetheless an art to pulling off an effective con. Some are so outlandish, so conniving, and so audacious that we can't help but be fascinated. (So long as we're not the targets, naturally.) Thanks to the internet and the digital nature of scams like phishing, it's getting harder and harder to add that personal touch. But once upon a time, cons were up close and personal. Check out 21 examples of hoaxes, impersonations, and other grifts that history won't soon forget.

1. The fake nurse who profited off a pandemic

Even by the low standards of the con game, Julia Lyons stands out as one of the most diabolical. During the 1918 flu pandemic, Lyons (under false names) "volunteered" in Chicago as a nurse to care for indigent patients at their homes. While she had plenty of training in cashing stolen checks, she had no medical background to speak of. She was counting on the fact the country was so desperate for health care workers that no one would inquire too deeply, and she was right.

Lyons wasn't as concerned with offering the sick some relief as she was relieving them of their funds. In addition to the standard theft of cash and valuables, Lyons would fill inexpensive prescriptions and then tell the patient they cost substantially more, like the one unfortunate who paid $100 for a $5 supply of oxygen. She was eventually caught and served time, but not before escaping custody and insisting she had been coerced into a life of crime.

2. The man who sewed goat testicles into people

The con world is full of wellness claims that rarely stand up to scrutiny. Even by those standards, John Brinkley — who was awarded his medical degree by a disreputable diploma mill — was one of a kind. His methodology for restoring virility in men took more from science-fiction than modern medicine. In the early 20th century, Brinkley pushed a procedure in which he implanted goat testicles into humans while insisting the surgery cured impotence, infertility, and even excessive flatulence.

Brinkley's absurd "treatment" seduced plenty of patients seeking remedy for such issues, paying the Kansas resident as much as $750 (over $10,000 today) to insert the goat genitals. He became a media star, with his own radio station that hyped his procedure and a self-congratulatory book, "The Life of a Man." Brinkley was also a Nazi sympathizer who added swastikas to his swimming pool.

In the late 1930s, Brinkley sued a critic skeptical of his claims for libel. Brinkley lost, and also lost on appeal — opening the floodgates to malpractice lawsuits. He went bankrupt and died in 1942.

3. The Hollywood con queen

Beginning in 2015 (and according to some sources, even earlier), a mysterious person began placing phone calls to a multitude of Hollywood hopefuls, using a feminine voice and assertive tone to convince them that they were an industry power player. Sometimes they would claim to be Deborah Snyder, the producer and wife of director Zack Snyder. Other times they said they were Lucasfilm head Kathleen Kennedy. The phishing scams led victims to Indonesia, ostensibly on a film job, before bilking them for travel expenses — a scheme said to have earned the con artist hundreds of thousands of dollars. Journalists Vanessa Grigoriadis and Josh Dean covered what they called "one of the weirdest and wildest scams in history" in the 2020 podcast "Chameleon: Hollywood Con Queen," and later that year, a suspect was arrested in the UK: Food blogger Hargobind Punjabi Tahilramani, who is currently awaiting possible extradition to the United States.

4. The man who sold the Eiffel Tower

As is probably fitting, much of the life of Victor Lustig is unclear, including his name (when he was at Alcatraz, he was held under Robert V. Miller). Lustig was a famous counterfeiter, but it's said his biggest swindle came in 1925, when he had documentation arranged identifying him as the "Deputy Director General of the Ministère de Postes et Télégraphes." The premise was simple: Lustig set up meetings with scrap iron dealers and told them that the Eiffel Tower, then in desperate need of repair, was going to be demolished and its materials sold off to the highest bidder. All of the dealers were interested, but Lustig fixated on André Poisson, asking Poisson for a bribe in order to "award" him the materials. After securing the money, Lustig fled France but soon returned to perpetuate the same scam a second time. (He guessed, correctly, that Poisson would be too embarrassed to tell anyone of the con.)

5. Sidney Poitier's "son"

David Hampton, who was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1964, found himself in New York City as a young adult in the early 1980s. Rather than face the city as a man with no social connections, he perpetuated an elegant and simple lie: His name was David Poitier, he was the son of acclaimed actor Sidney Poitier, and he was down on his luck because he had just been mugged, or had lost his luggage. The ruse got Hampton unprecedented access to wealth and influence, and he accepted everything from clothes to money from impressed members of the social elite before he was eventually discovered and arrested; the ploy netted him a sentence of 21 months in prison. His story loosely inspired "Six Degrees of Separation," a play that was later turned into a 1993 film starring Will Smith. (Hampton tried and failed to get a cut of the play's profits before his death in 2003.)

6. The Poyais affair

In 1822, Scotland native Gregor MacGregor talked up Poyais in modern Honduras, making it sound irresistible: He told people it was incredibly fertile, had endless gold in the river, and boasted beautiful cathedrals. Soon, investors were flocking to seize their chance at a fortune; MacGregor collected 200,000 pounds and sent ships full of eager settlers on their way. But when the settlers arrived, they found swamps instead of gold and endless fields, and the people began dying off due to scarce resources in the desolate area. Only a third made it back alive. MacGregor tried the scheme again, this time after fleeing to France, but people grew wise to his tricks and he began to roam to avoid retaliation. He died in 1845.

7. The counterfeit Kubrick

If you're going to impersonate a living film director, Stanley Kubrick was a terrific choice. While venerated for his films like "The Shining" and "Full Metal Jacket," the reclusive Kubrick was not as familiar a face as Steven Spielberg or Martin Scorsese. That left the door open for Alan Conway (born Eddie Alan Jablowsky) to perpetuate a lie that he was the director. For a period of time in the early 1990s, Conway spirited around England claiming to be Kubrick and found willing listeners in theater critics, actors, and others in the entertainment industry. While his spoils amounted to little more than free dinners and backstage access (though Kubrick's widow would charge that Conway was "seducing little boys with the promise of a part"), Conway managed to carry on for years. Curiously, both he and the real Kubrick died within a few months of each other in 1998 and 1999, respectively.

8. The man who "revealed" Howard Hughes

A writer of little regard in the 1970s, Clifford Irving concocted a literary scheme for the ages. He approached publisher McGraw-Hill in 1971 claiming that he had struck up a rapport with eccentric aviator and billionaire Howard Hughes, who had largely retreated from public life. Irving's con was simple: He offered editors an autobiography of Hughes, one he would secretly invent out of whole cloth, and bank on the fact that Hughes would never come forward to debunk it. After netting hundreds of thousands of dollars for various publishing deals, Irving was dismayed to discover Hughes could indeed be bothered to come out of hiding and deny any knowledge of Irving or his book. (Though to Irving's credit, he was so convincing that some believed it was "Hughes" who was lying and simply regretted collaborating on a book about his life.) In 1972, Irving and his wife and co-conspirator, Edith, pled guilty to conspiracy in federal court and conspiracy and grand larceny in state court. Irving went to prison for 17 months, but a book did materialize: 1972's "Clifford Irving: What Really Happened" (later retitled "The Hoax"), in which Irving recounted the con in detail. Irving, who died in 2017, said he thought it was a harmless "joke" and that he would do it again if given the chance.

9. The golden gulch gold mine

The secret to good business for Ed Barbara, a furniture salesman in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1970s and 1980s, was irritation. Barbara became a well known figure by peppering the region with annoying commercials. He also did more than just irritate: In 1984, Barbara declared he had a 50 percent interest in the Golden Gulch gold mine near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico. The site was said to be prepared to excavate gold worth as much as $93 million in the first year alone; Barbara's company, Dynapac, Inc., sold shares, netting Barbara big profits.

It was a con, of course. A whistleblower, mine assayer David Fingado, disclosed the mine was meritless to CNN. Less than a week later, he was dead after a highly suspicious car crash (though the official report determined it was an accident). Barbara fled before being hauled back to New Mexico to stand trial on fraud and racketeering charges. He racked up guilty verdicts in 1988 but fled on bail and remained a fugitive until his death in 1990.

10. The man who claimed to be Clark Rockefeller

For years, Christian Karl Gerhartsreiter — who was born in Germany — passed himself off as Clark Rockefeller, one of the members of the oil-rich American dynasty. Using this identity, he found himself surrounded by wealth and wound up marrying financial lawyer Sandra Boss and becoming a stay-at-home dad to their daughter. They divorced in 2007, and in 2008, Gerhartsreiter took the child with him to Baltimore where he had assumed another identity as a yacht captain. While authorities found them, a darker secret emerged: Gerhartsreiter had murdered his landlord, John Sohus, in 1985, a crime for which he was finally found guilty in 2013.

11. Hitler's diaries

It was the journalistic coup of the century: In 1983, "The Sunday Times" of London published diary entries purported to be from the hand of the 20th century's most infamous figure, Adolf Hitler. The paper's editor, Frank Giles, had taken care to authenticate the diaries with a well-respected historian, who had deemed them legitimate. But they were actually the work of German forger Konrad Kujau, who profited from their publication in Germany and elsewhere. (Kujau sold 60 volumes of the faked diaries to German publication "Stern" for $4.8 million.) The "Sunday Times" learned at the very last moment that the work was a fake, but the paper's owner, Rupert Murdoch, ordered the story about the diaries to be printed anyway. Kujau was later found guilty of fraud and served three years in prison. After being released, he got in more legal trouble thanks to possessing several unlicensed weapons. A German judge told Kujau that he was "very apparently a man who is attracted by that which is illegal."

12. The Le Drian mask

Tom Cruise ripping off a silicone mask in the many "Mission: Impossible" movies may not seem believable, but it really depends on your screen resolution. In 2020, Gilbert Chikli and Anthony Lasarevitsch were convicted of impersonating French defense minister Jean-Yves Le Drian and defrauding victims of 55 million euros in 2015 and 2016. The duo sometimes set up Skype meetings with their targets, one of them on camera and wearing a silicone mask of Le Drian in order to petition for help with political imbroglios. Such assistance usually required money, which the pair collected from three victims out of the 150 they approached. Had they not been caught, they were apparently planning on impersonating Prince Albert II of Monaco next.

13. The NASCAR driver who wasn't

It takes guts and glory to drive on the NASCAR circuit. Alternately, you could just lie your face off and hope for the best. That was the strategy for L.W. Wright, who entered the Winston 500 race in Talladega, Alabama, in 1982 and who (falsely) claimed country music star Merle Haggard was a sponsor. Wright then went around in search of a race car and convinced several race veterans to part with money so he could get some wheels under him. All of it seemed on the level because it seemed preposterous anyone would lie about being a NASCAR pro. Wright performed poorly, completing just 13 out of 188 laps — enough for second-to-last place, because the car in last place crashed — and then disappeared in a haze of bounced checks and no real hint as to his actual identity.

14. The amateur physician

Ferdinand Waldo Demara, a Massachusetts native, had a dilemma: He wanted a life of prestige and respect, but he had left school at the age of 16 in 1935. Professions requiring extensive education seemed out of the question ... or were they? After joining the Navy, he forged documents that allowed him to advance in medical school — and then decided to leapfrog medical school and get a commission. When faced with discovery, he faked his own death. Several misadventures later, he eventually appeared as "Cecil Hamann," attendee of Northeastern University's law program. Then Demara decided he would simply forge more papers to award himself a Ph.D. In the 1950s, he joined the Canadian Navy, convincing them he was a physician, and used his passing knowledge of medicine to treat people during the Korean War — including one leg amputation, which he performed successfully. He was discovered, after which his story appeared in "Life" magazine. After trying to "go straight," he soon took another identity and became a prison guard. He was eventually discovered once again, spent time in prison himself, and, after his release, began to publicize his wayward ways on television and in print. He died in 1981.

15. The trunk scam

In the 1700s, Barbara Erni traveled in and around Liechtenstein toting a large trunk secured to her back. Living a nomadic existence, she would make frequent stops to secure lodging for the night. Each time, Erni would tell the innkeeper that her trunk contained her most valued possessions and to put it in the most secure room in the inn. The owners obliged, unaware that the trunk didn't hold clothes or jewels — it contained a co-conspirator who would spring out of the trunk, scoop up any valuables, and then disappear with Erni in tow. The plot worked for 15 years until Erni and her partner were arrested in 1784. As a sentence for their crimes, the two lost their most valuable possessions: their heads.

16. The pre-Columbian pottery scam

In 1974, Brígido Lara was among a group of people who were arrested and accused of looting pre-Columbian ceramic artifacts. But Lara steadfastly denied that any looting had taken place because, he said, none of the artifacts were real — he had crafted them himself. Lara admitted to creating clay sculptures mimicking works from Mesoamerican cultures and then selling them—and though he claims he never passed them off as authentic, "I was aware that many buyers then sold them as authentic pre-Hispanic works," he told Art and Antiques Magazine.

Facing 10 years in prison for robbing cultural pieces, Lara convinced his jailers to give him some clay and tools so he could prove he could fashion them by hand. After his release, the Museo de Antropología de Xalapa offered him a job. While Lara went straight, the effects of his efforts continued to reverberate. His fake pieces showed up regularly in museums and at auctions around the world, which Lara would then have to debunk. Some art historians believe there are Lara creations out there that are still believed to be the real thing.

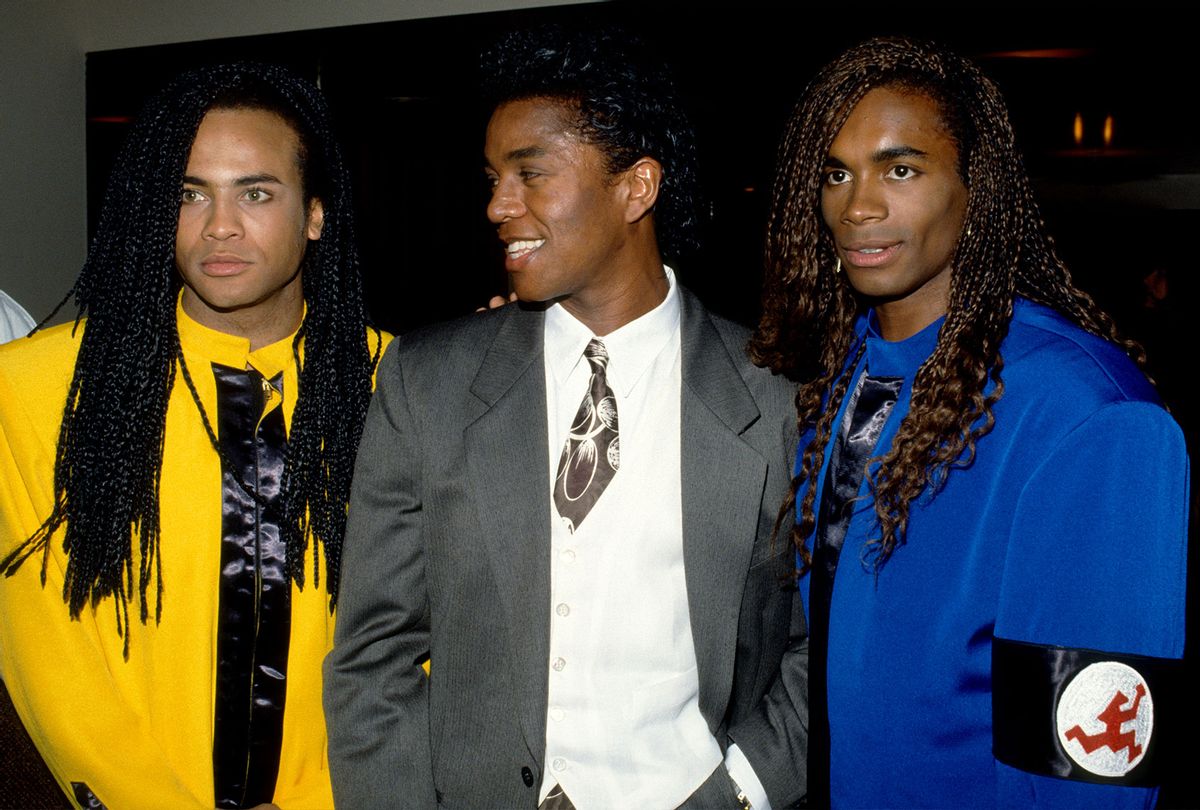

17. The record-setting con

In the late 1980s, pop music heralded the arrival of Milli Vanilli, an energetic song-and-dance duo that had a hit album, "Girl You Know It's True," and the Grammy for Best New Artist. Performers Rob Pilatus and Fab Morvan certainly looked the part of pop stars, with model looks and sharp dance moves. They had come out of the Munich music scene and were signed by producer Frank Farian, who decided that a complete pop package would need something more — like singing talent. Farian masterminded a plot in which Rob and Fab would be the faces of Milli Vanilli while other vocalists did the heavy lifting. Farian later claimed he didn't know the act would get as big as it did. After three number one singles and worldwide adoration, the band was subjected to more scrutiny, and Rob and Fab started demanding to do their own singing. Rather than allow that, a panicking Farian held a press conference where he disclosed the truth. Today, some argue Milli Vanilli has been unfairly demonized, with music journalist Bryan Reesman noting, "If we had decided the group's debacle was the end of lip-syncing and digital manipulation and had raised our standards, it would be easier for us to justify how we derided them. But it did nothing more than grease the wheels for the tricks and manufacturing of musical performances we eagerly consume today."

18. The world's littlest skyscraper

Few people would consider a 40-foot-tall building to be in skyscraper territory, but it really depends on your context. Local legend has it that in 1919, a building in Wichita Falls, Texas, was constructed after an investor named J.D. McMahon convinced residents he was going to build a massive property stretching far in the air. After collecting $200,000, he erected a building that was just four stories tall, 10 feet wide, and 16 feet deep — the measurement in the paperwork was in inches instead of feet, an important detail overlooked by investors.

McMahon ran off with his windfall; the resulting embarrassment was dubbed "the world's littlest skyscraper" and even drew the attention of Ripley's Believe It or Not!, which made it a local curio that's still standing today.

19. The soccer player who never played soccer

In 1980s and 1990s Brazil, Carlos Kaiser was one of the country's most unlikely soccer (a.k.a. football) players, bouncing from team to team and relishing his reputation as a party animal. But even a cursory glance at Kaiser's career revealed something remarkable: He hardly ever stepped on the field. Kaiser was adept at spinning yarns of his prowess to get on a team, then fake an injury that would serve to keep him sidelined; he even bribed spectators to chant his name. He perfected the illusion of the sports hero without the need for all of the practicing or talent.

20. A bridge to sell you

There was a time when "I've got a bridge to sell you" was not a way of casting doubt on a party's intellect but an offer meant to be taken seriously. Although it's difficult to tell folklore from fact, it's said that George C. Parker secured deals for the Brooklyn Bridge (which was completed in 1883) for gullible buyers by preying on their ignorance of American business and American cons. Many victims were immigrants who knew only what Parker told them: If they owned the bridge, he reasoned, imagine the money to be made in tolls. After "selling" the bridge, Parker would vanish while the marks were chased off by police for having the temerity to begin erecting toll barriers. Parker wasn't the only one to perpetuate the scam, either; supposedly, brothers Charles and Fred Gondorf would dodge police near the bridge then quickly put up a "for sale" sign, duping buyers and dashing off.

21. The mystery princess

In 1817, residents of the tiny English village of Almondsbury began gossiping about a strange visitor in town. Her name was Caraboo, and in an exotic tongue, she told an interpreter that she was a princess from an island in the Indian Ocean called Javasu who had fled from pirates. The humble town was honored to have actual royalty within reach, and soon local officials began throwing her expensive parties in an effort to treat her to the luxurious lifestyle they believed she was accustomed to.

But Javasu was fictitious, and Princess Caraboo had no royal lineage. She was actually Mary Baker, a cobbler's daughter. A boarding house owner recognized Baker from a newspaper description; suspicion grew until it reached the ears of Mrs. Worrall, wife of Almondsbury's magistrate Samuel Worrall. She accompanied Caraboo to Bristol under the guise of inviting her to sit for a portrait so the boarding house owner could identify her. Baker confessed to the ruse, claiming that she had sought a way out of poverty by literally faking it until she made it.

Strangely, public opinion wasn't all negative: Some appreciated Baker's moxie, and she later staged a moderately successful live show based on her story. A film about her grift, "Princess Caraboo," was released in 1994 and starred Phoebe Cates.

Shares