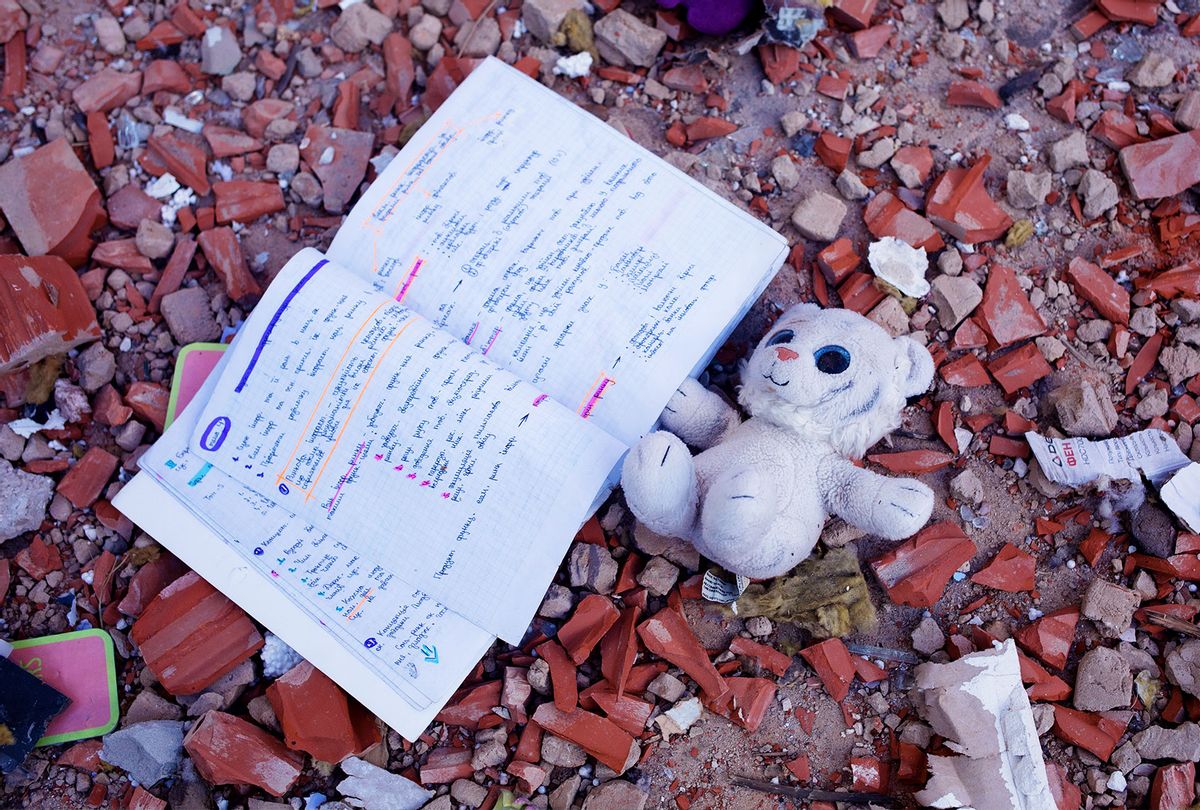

Last week, a startling but seemingly familiar story emerged on the periphery of the Ukraine war: A former Washington state representative named Matt Shea, long associated with the far right, turned up in a hotel in a small Polish town with 63 Ukrainian children he apparently hoped to bring to the U.S. for adoption. For those who have followed both Shea's career and the recent history of evangelical Christian adoption advocacy, this was cause for alarm.

Over his six terms in the Washington House of Representatives, Shea maintained close ties to "Patriot" and militia groups. He became involved in the armed occupation of Oregon's Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 2016 and proposed legislation to transform rural eastern Washington, a heavily conservative region, into a 51st state to be called "Liberty." Shea partnered with a group that ran a training camp to instruct youth in "Christian warfare," and authored a pamphlet called "Biblical Basis for War" that appeared to offer advice to Christian "patriots" readying themselves for war against Muslim and Marxist "terrorists" (and which included a proposal to "kill all males" who resisted the new theocratic order they'd establish). Shea has maintained that document only amounted to notes for a sermon, but he also reportedly wrote an eight-page plan for the restoration of civilization after a civil war and governmental collapse (including banning all "centralized" education and medicine, implementing "severe" penalties for anyone seeking to limit public religiosity, and reinstating the death penalty for murder, rape, "sodomy" and possibly adultery — a provision marked for discussion).

RELATED: Republican legislator in Washington state accused of "domestic terrorism"

Shea's record led his state House colleagues to commission an independent investigation into his far-right associations. In 2019, that probe concluded that Shea's activities amounted to support for "domestic terrorism," after which he was stripped of his committee assignments and suspended from the legislature's Republican Caucus. He didn't run for reelection in 2020, but instead transformed himself into a pastor, and now leads his own church, On Fire Ministries.

This month Shea and a group of his supporters, drawn from both the U.S. and Polish far right, reportedly set up camp in a hotel in Kazimierz Dolny, a small town in eastern Poland about three hours from the Ukrainian border. They were accompanied by dozens of children Shea claimed had been evacuated from an orphanage in the besieged city of Mariupol. When an aide to the local mayor went to the hotel to find out what was going on, she said Shea refused to explain himself or even give his full name. In an interview with a right-wing Polish television show though, he claimed to be working with a Texas group, Loving Families and Homes for Orphans, that arranges for American families to host Ukrainian children on a short-term basis, with the ultimate aim of facilitating adoptions.

After the Seattle Times and a number of other media outlets began investigating, Shea's plans appeared murkier still. Loving Families and Homes for Orphans wasn't a registered adoption agency and its website didn't work. Shea pointed supporters to a different website that seemed to have been recently created and contained language, as journalist Daniel Walters noted, that appeared to have been copied word for word from other hosting groups.

Although Loving Homes has been registered as a business entity in Texas for several years, the group registered itself anew in Florida in mid-February, under the names of at least two individuals connected to Spokane, Washington, Shea's hometown. The addresses listed for the organization, and for two of its three officers, appear to be vacant lots.

One of Shea's allies, former Spokane Valley City Councilman Mike Munch, told Walters that Shea was trying to adopt four children from Ukraine, and an American volunteer with Shea's party said the group's hope was to take the children to America soon. But after the media attention, Shea denied any such plan, complaining on Facebook that his critics didn't understand the distinction between hosting programs and adoption. Talking Points Memo's Matt Shuham, however, reported that Shea delivered a sermon in a Polish church describing his efforts to "bring these orphans home" — standard language in the adoption world for finalizing an adoption — and also to "bring them home to the father," an almost certain reference to Christian evangelism.

Shea has accused his critics of deploying "Russian-style propaganda" to bring "politics and religion into a humanitarian issue." And on a March 17 livestream show, "Church & State," which is linked to Shea's ministry, he argued that the coverage had distressed potential adoptive parents in particular. "You have a lot of very, very upset parents right now who were ecstatic that their kids were rescued out of a war zone, brought to safety, and now the media is literally trying to put some insidious motivation behind this," Shea said, "when really it's about making sure there's no more orphans in the world."

* * *

Whatever Shea's agenda may be, he's not the only person who sees the crisis in Ukraine as a moment that may call for the large-scale adoption of children. On social media, numerous people have posted requests seeking information on how to adopt, host or foster a war "orphan" from Ukraine. Former Real Housewife Bethenny Frankel announced on Twitter that she had an apartment building standing ready to house 157 orphans currently taking refuge in Poland. In the U.K., a brief political battle broke out between two members of Parliament after one accused the other of slowing the transport of 48 purported Ukrainian orphans to Scotland, while the second charged that it was "wrong to move children without attempting to reunite them with their family first and without the agreement of their home and host governments."

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

That sort of explanation — both in the British skirmish and in broader internet debates about Ukraine's vulnerable children — was met with variations of the response, "Don't you know what 'orphan' means?" as though explaining for the simple-minded that orphans by definition are children without parents.

That may be the dictionary definition, but it's not true in the world of adoption, where many children who live in institutional care have living parents or other kin who have no intention of giving them up. Amid emergency circumstances, whether natural or manmade, it's often simply impossible for officials tasked with determining which children are actually eligible for adoption, and which are not, to do that job. And that vacuum can create situations ripe for exploitation.

That was certainly the case in Haiti in 2010 with the notorious case of Laura Silsby, a woman from Idaho who was arrested trying to take 33 children across the border into the Dominican Republic without paperwork or permission. Silsby led a group of 10 Baptist missionaries who had flown to Haiti in the aftermath of that year's devastating earthquake, on a vague mission to help.

Her plans were more specific: With her personal and business life in shambles, Silsby seemingly intended to reinvent herself as the head of an orphanage in the Dominican Republic where Christian couples from the U.S. would stay in "seaside villas" while waiting out that nation's adoption residency requirement. When the earthquake hit, she devised a scheme to drive a bus through Haiti "and gather 100 orphans from the streets and collapsed orphanages, then bring them back to the DR," where she had leased a 45-room hotel. Instead, when the bus reached the border, Silsby and her missionaries were arrested and charged with kidnapping and criminal conspiracy.

Many other evangelical Christians and adoption advocates denounced Silsby as a bad apple who gave international adoption a bad name, especially after it turned out that all 33 children she'd tried to abduct had at least one living parent or other close relatives. Silsby protested that she was being punished for something many other people in the adoption world had gotten away with. She had a point.

What Silsby tried to do "has been done a million times in human history, especially after disaster," said Canadian global development professor Karen Dubinsky, the author of "Babies without Borders: Adoption and Migration Across the Americas." After catastrophe, she continued, a form of "disaster rescue" often emerges as a parallel to disaster capitalism: "You can do almost anything in the name of rescue, and so much more so when it comes to child rescue." And the process has become "almost seamless: Disaster happens and we in the West show up with bottled water — and we'll take your children."

It happened in 2005, after the Indian Ocean tsunami that killed a quarter of a million people in 14 countries, prompting one American missionary group to announce its effort to "airlift" 300 Muslim children out of one devastated province and raise them according to "Christian principles." It happened two years later in Chad, when a French charity was accused of kidnapping 103 children it claimed were Sudanese war orphans, but in many cases were just local kids with families.

After the Haitian earthquake, while adults in that nation were warned not to try to seek asylum in the U.S., the drive to expedite adoptions rose to fever pitch. The U.S. government began following new guidelines of "humanitarian parole" to fast-track the paperwork of about 1,200 children who were already somewhere in the adoption process. But soon after that came efforts to expand the loopholes even wider and transport children out of Haiti who had no adoption plans in place, or whose parents hadn't signed off on them leaving.

Media coverage grew increasingly focused on the plight not just of Haitian "orphans" but prospective adoptive families in the U.S., and a strange counterfactual language took hold, calling for the "repatriation" of Haitian kids who'd never been to America, or their "reunification" with families they often had never met. Headlines called for flying children out of the country now, and sorting out "the paperwork" later, even though children with ambiguous legal status who end up in American families' homes are often not returned.

Politicians joined the chorus, lobbying to speed adoptions up, or warning that recalcitrant aid groups like UNICEF — one of many groups that warned against fast-tracking earthquake adoptions — might lose their funding if they stood in the way. In Pennsylvania, then-Gov. Ed Rendell, a Democrat, muscled through the evacuation of 54 children from a Haitian orphanage run by two Pittsburgh sisters — including 12 children whose families had not agreed to adoption, and in at least one case didn't find out their child was gone until they visited the orphanage.

A version of this story may now be unfolding in Ukraine. "Out of the children in orphanages or shelters, only about 10 percent are actually available for adoption," said Teresa Fillmon, the American director of a Ukraine-focused children's organization, His Kids Too!, and the former director of an agency that facilitated adoptions from eastern Ukraine before Russia's 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Most of the kids in such institutions, Fillmon said, are there because a parent "might be in jail, might be sick in the hospital, might be doing a number of things that there is no one able to take care of the children. They're usually there in a temporary situation."

When war came to Ukraine, the nation's Ministry of Social Policy declared a moratorium on adoptions, explaining that it was impossible to properly vet the documentation of either prospective adoptive families or the status of potential adoptees. The National Council for Adoption in the U.S. has echoed this, saying: "It is paramount that the identities of these children and their families be clearly established, and their social, legal and familiar status is fully verified by government authorities. For many of these children, we cannot do that at this time."

* *. *

Around the same time that Laura Silsby was making headlines, I reported on a surprisingly similar plan unfolding in Alabama, albeit one with a much more sympathetic face. In early 2010, Alabama pastor Tom Benz announced his intention to "airlift" some 50 to 150 Haitian children out of the country and bring them to a church retreat center he had recently acquired halfway between Montgomery and Birmingham, from which he hoped the children might be adopted to local Christian families. Benz raised funds for this plan, using donations and volunteer help to overhaul the retreat center's aging infrastructure. While that was happening, he told reporters that he planned to skirt the tense politics around unauthorized adoptions out of Haiti by presenting his program to authorities there as a "cultural exchange."

But by late 2010 his Haiti plan had fallen apart and Benz shifted his focus to Ukraine, where his wife had been born and where he'd worked earlier in his career, handing out Bibles after the collapse of the Soviet Union. That December, Benz brought over his first group of "orphans," and he has done so, at a pace of several groups per year, ever since, amounting to around 500 children hosted and close to 200 adopted.

At the time, Benz admitted that his program was walking a blurry line. "Our program in Ukraine, if it were about adoption, it couldn't happen," he told me. Each group of children he flew over prompted a new letter from the U.S. embassy in Kyiv, telling him the purpose couldn't be adoption. "Everyone knows it's about adoption," he said, "but it can't be about adoption."

It couldn't "be about adoption" because the Ukrainian government was seeking to retain more control over its child welfare programs than often happens in an international adoption industry that can function like a boom-and-bust market. As the nation developed and grew more stable, it sought to promote domestic adoption by Ukrainian parents. It also wanted to prevent the sort of scandals that had happened in the first years after the country's independence, including one episode in the early 1990s when dozens of Chicago-area families refused to return Ukrainian children they were hosting and wanted to adopt.

When I visited Benz's retreat center in 2011, it was obvious the line was often blurred beyond legibility. Staff at the center warn visitors to never use "the 'A' word," but each group of children was accompanied by an independent Ukrainian adoption facilitator, who stood to earn thousands of dollars for every successful adoption they completed. Children were painfully aware that their presence wasn't just an American vacation but an unofficial audition for families who might whisk them into a new life — a reality underscored when I drove into the center and my car was surrounded by a half-dozen Ukrainian kids, opening doors and shaking my hand, eager to make a good first impression on any adult who arrived.

Ukraine has tried to prohibit foreign groups from sharing photos or information about children available for adoption, and, at least technically, bans most "pre-selection" adoptions — that is, foreign parents requesting a specific child.

Fillmon says both these rules have been broken by some groups working in Ukraine. But amid the chaos of the war, as she fields calls from people asking whether it's possible to go to Ukraine to "get some children," she worries about what the new disorder could bring.

"It makes me think about the children that came across the border from Mexico" under the Trump administration's family-separation policy, she said. "There's [hundreds of] children that they still can't find their parents. I wouldn't want that to happen in Ukraine." She sketches out scenarios in which children are dispersed into foster homes in the U.S., where the foster parents later become unwilling to send them back to a country that, no matter the outcome of the war, is likely to be a difficult place to live in coming years.

Nonetheless, pressure is beginning to mount. Media coverage focusing on prospective adoptive parents often includes suggestions that the public urge their legislators to expedite adoptions, or casts Ukraine's adoption moratorium in ominous tones.

In early March, Tom Benz announced in a press release that he was working to shuttle eight or nine Ukrainian children who had come to Alabama last December into neighboring countries, in hopes that they can be moved through the adoption process "on their way to the U.S." One prospective adoptive father made national news as he and Benz traveled to Poland in hopes (so far unmet) of bringing some of the children back.

On Monday, Rep. Deborah Ross, D-N.C., called on the State Department and Homeland Security to begin expediting international adoptions from Ukraine, specifically calling for the reinstitution of the humanitarian parole program that sped up adoptions from Haiti 12 years ago.

Despite the echoes of the child welfare missteps in 2010, Dubinsky says she hopes things might be different this time: After more than a decade of falling international adoption numbers, many adoption advocates have begun embracing family preservation or local child welfare alternatives instead. As generations of adoptees have come of age and begun to speak for themselves, public discussion of adoption and its consequences has become more nuanced and complex.

"My impression is that the rescue narratives that came very easily to people's lips in Haiti" do not come as easily now, Dubinsky said. "The idea that adoption is always good, adoption is rescue, just grab the children and sort out the details later — that story has become more complicated."

Read more from Kathryn Joyce on the far right:

Shares