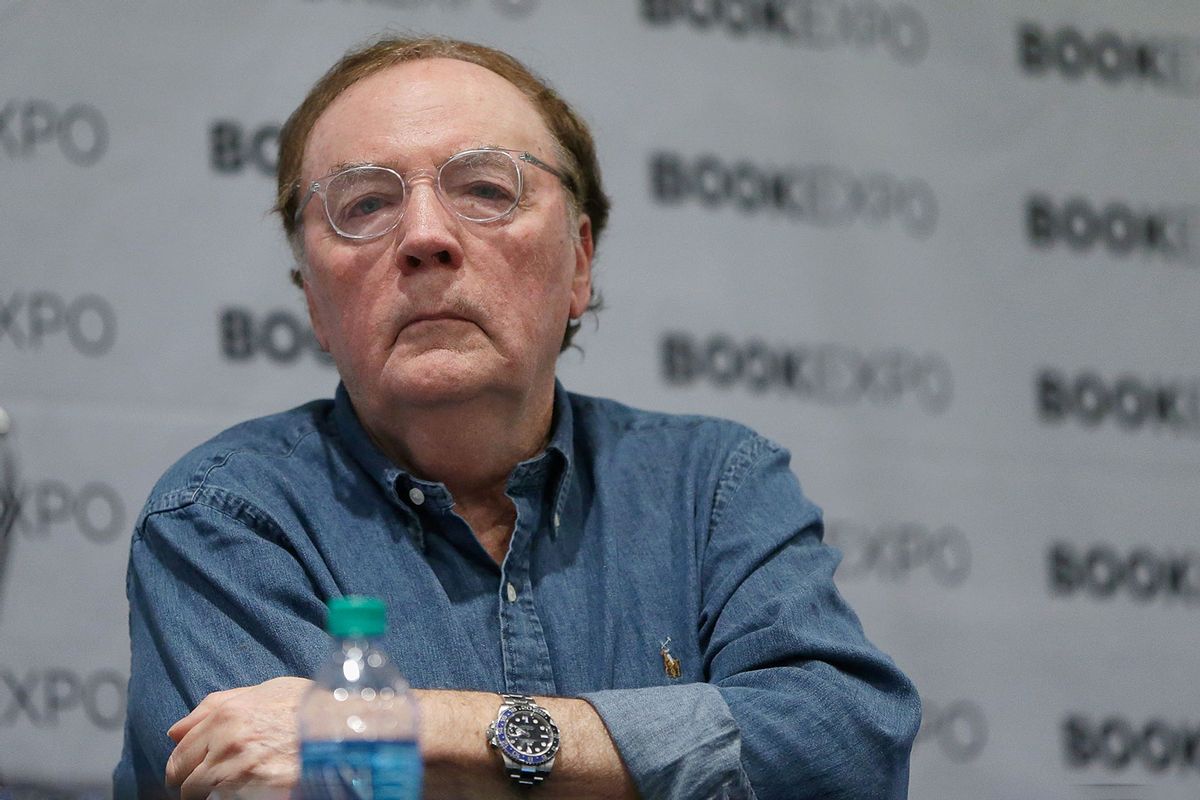

One of richest living writers in the world, James Patterson, said in an interview with The Times on Sunday that white men like him face racism within the publishing, theatre, and film and TV industries. He described the alleged difficulty confronting the most privileged members of society as "just another form of racism. . . . Can you get a job? Yes. Is it harder? Yes. It's even harder for older writers. You don't meet many 52-year-old white males."

Citing industries almost entirely dominated by white men, Patterson doesn't have the facts on his side. The respected Lee & Low Books Diversity Baseline Survey reported in its 2019 findings that 76% of the publishing industry is white. According to a different 2020 study, 95% of published writers are white. Male writers receive more attention, acclaim and income than female writers, with 75% of books reviewed in the prestigious Times Literary Supplement written by men. Books about women are less likely to win prizes (which can translate into sales). Their titles receive about "half (45%) the price of male authors' and are underrepresented in more prestigious genres."

On the performance side, a study from The Asian American Performers Action Coalition found almost 90% of playwrights who had their works staged in the 2016-17 New York season were white and male (87.1% of those performances were directed by white directors). As Playbill reported: "On Broadway alone, 95% of all plays and musicals were both written and directed by Caucasian artists" while 89% of Broadway-produced playwrights were male.

Hollywood has a similar record. In 2019, over 85% of directors were white and over 84% were male. In 2017, only 11% of the year's top 250 films were written by women.

Good thing Patterson doesn't publish nonfiction (wait, he does — sort of). Is this a matter of an extremely wealthy older white person continuing to be out of touch? Yes. Is this racism manifesting in a gross form? Yes to that too. (It's also strange that a 75-year-old would call a 52-year-old "old")

But is this also a publicity stunt by an expert at the con? Maybe.

RELATED: James Patterson laments white male writers are facing racism, and then receives immediate backlash

Since 1976, the Patterson name has been embossed on hundreds of novels you can find at airports; 260 were New York Times bestsellers. He may not even know how many he's published, as he didn't write all of them.

Co-writers fuel his productivity which is, as The New Yorker wrote, "the secret of Patterson's success . . . Like the Stratemeyer Syndicate, which, in the early 20th century, produced hundreds of novels for young readers, featuring such characters as Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, Patterson supplies detailed outlines for his books. His co-writers then flesh out these narrative skeletons into installments of popular series."

When I lived briefly in New York in my 20s, I met one of Patterson's writers, a young man in a very nice suit. He was supporting himself and his family thanks to the Patterson machine though not, I believe, writing his own work, which is what most writers set out to do.

How does a writer become a brand? It's complicated. But it helps if you're in the business of branding to begin with.

The many popular series of Patterson include the genres of thriller, crime, romance, mystery, comedy, science fiction, children's books and YA (he once described his foray into young adult writing as "I can write for these little creeps"). His Alex Cross books were adapted into films. Many of his books have been.

Vanity Fair, which once called him the "Henry Ford of Books," says that he employs an "army" of co-writers, like the one I met. But The New Yorker points out that, unlike some other writers who rely on ghost writers, "Patterson credits his co-writers, even if his eminently bankable name appears in much larger type on their books' covers."

How does a writer become a brand? It's complicated. But it helps if you're in the business of branding to begin with.

Most don't even have final say over titles or covers, especially not those writers of color that Patterson claims are so advantaged.

In that same article, Vanity Fair writer Todd Purdum describes Patterson as an "advertising Mad Man," which he was. Patterson had a lengthy first career in advertising, working his way up from copywriter to C.E.O. of the North American branch of huge international ad agency J. Walter Thompson. He also worked as its creative director. Among his inventions, the lyrics for the Toys R Us jingle, which will be stuck in my head until I die: "I don't wanna grow up. /I'm a Toys R Us kid."

Patterson also led the "Aren't You Hungry?" Burger King campaign, another hugely successful and popular campaign, which included an ad featuring Meg Ryan behind a fast food counter.

Patterson worked for 25 years in advertising. (He keeps the industry's highest award, a Clio, in his office along with writing awards.) He had to have picked up some tricks. When his publisher, Little Brown, refused to do a TV ad for his book "Along Came a Spider," Patterson did it himself, ensuring the book's success.

Patterson's former life, the business of advertising, is, in a sense, the business of cons.

He helps design his books and their advertising campaigns, which is something only the most powerful of traditionally published writers are allowed to do. Most don't even have final say over titles or covers, especially not those writers of color whom Patterson claims are so advantaged.

Patterson knows what he wants and what he's doing, and even though few people, maybe not even the writer himself, would call what he's doing art, it's certainly financially successful. With a net worth of $750 million, he earns an estimated $90 million a year, has a beachfront home in Palm Beach and enjoys summering in the toity Westchester County, New York village of Briarcliff Manor.

But Patterson's former life, the business of advertising, is, in a sense, the business of cons.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

From the claims of Airborne that it kills germs (the company had to pay over $23 million in a class-action lawsuit) to cosmetic companies cited for excessive photoshopping to a distorted image of the Whopper of Patterson's old client, Burger King, advertisements twist and tweak. They tell us what we want or hope to hear — or sometimes, what will inflame us.

As the quote goes from that most famous ad man, Don Draper, who once said he slept "on a bed of money": "If you don't like what's being said, change the conversation." Try to get it focused on what you want it focused on: you, as Patterson did with his remarks in yet another interview about this writer who published 15 books last year.

Patterson conned the world that he writes these books. Has he conned us again? Does he truly believe that white men actually face racism? And/or, is this yet another gimmick from the ad man, designed to get the creaky publicity machine grinding once more, determined to get his name in the press? We're talking about him, after all. And what's that they say about all publicity?

More stories like this

Shares