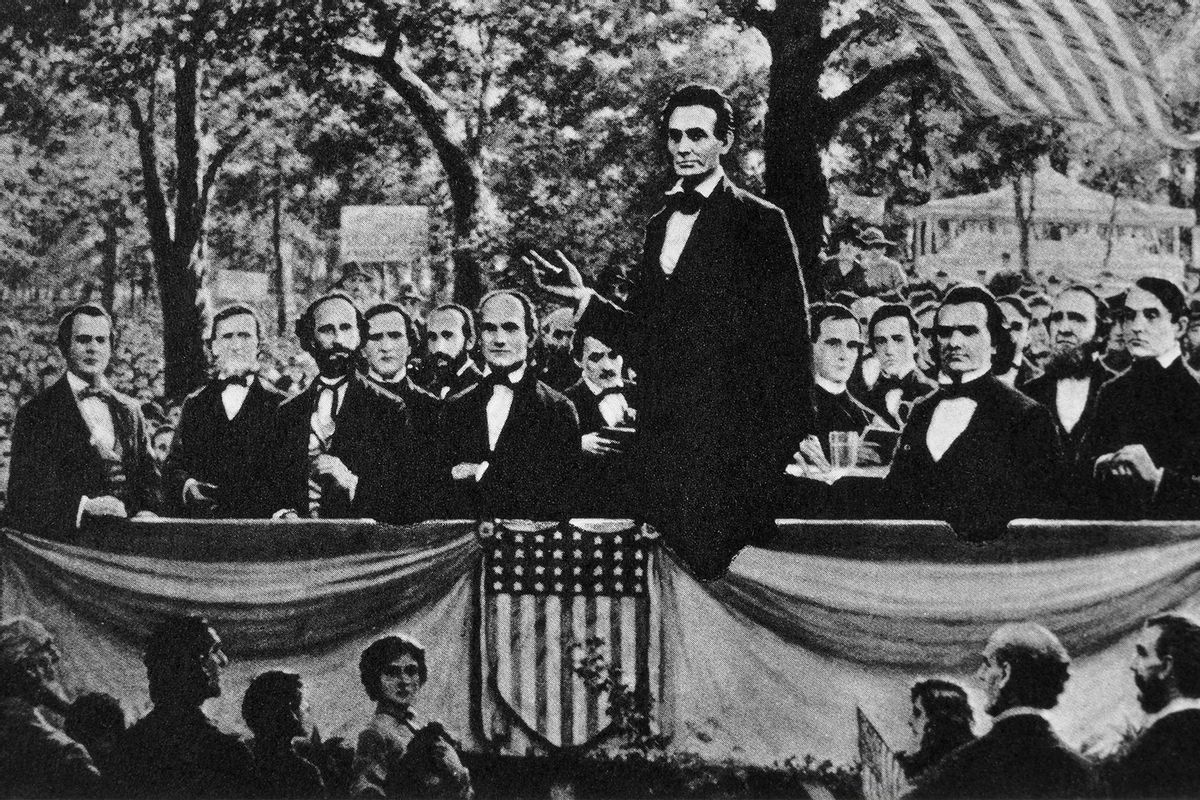

When Joe Biden met last week with a "select group of scholars" for a "Socratic dialogue" about America's future, the esteemed historians compared the current crisis facing our democracy with two other historical periods: The years immediately preceding the Civil War, which broke out shortly after Abraham Lincoln's victory in the 1860 presidential election, and the years before World War II, when proto-fascist or explicitly fascist movements like those led by aviator Charles Lindbergh popped up all over the land.

Yet there is a third, and closely related, chapter of American political history worth examining at this moment: The one that occurred not immediately before the Civil War, but during that conflict. Even during the worst carnage of the worst war in American history, elections were still held — a remarkable accomplishment all on its own. One of the two major parties of that period, the Democrats, who dominated the South and were largely pro-slavery (or at best not opposed to it) were severely depleted because so many of them had joined the Confederate rebellion. The Republicans, a party that had only existed for a few years, held commanding majorities, but in a climate of intense partisan division.

It would be ludicrous to suggest that Joe Biden can ever match Lincoln's legacy. Except, perhaps, when it comes to the question of how to handle Donald Trump.

This is uncomfortably similar to the United States today. While a handful of Republicans have denounced Donald Trump's coup attempt, most are either sticking with the disgraced former president or trying to find some (nonexistent) middle ground. So Biden faces with the question of how to deal with an opposition party that seems ready to tolerate or even encourage actual violent rebellion when it loses an election.

So how did Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans of his era handle this situation? First, it's important to note that congressional elections were quite different 160 years ago at this time. For one thing, they were scheduled in a manner that might seem bizarre to modern Americans. That was especially true during the 1860 elections, which were spread out over an extended period of time that included the secession of 11 Southern states, giving the Republicans (almost exclusively a Northern party at that time) overwhelming majorities in both depleted houses of Congress. In the Senate, Republicans held a 30-11 advantage, while in the House they held 105 of the 149 seats.

For a party that had only been formed in 1854, this was an astonishing opportunity to transform America, and the Republicans seized it. Going into the following midterms, in 1862-63, Lincoln's party faced intense public backlash for the Union's inability to end the war, the intense controversy around the Emancipation Proclamation, government policies that restricted free speech and civil liberties, and a range of economic issues, including inflation and taxes. Republicans lost 22 seats in the House but managed to hold onto effective control of that body — and actually gained three seats in the Senate.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In other words, because the Democrats both literally and figuratively relinquished power during Lincoln's presidency, the Republicans reaped political capital even during extremely adverse conditions. They spent some of that capital on the history-changing project of ending chattel slavery — the Emancipation Proclamation didn't actually do that, but it certainly started the process — and also pursued a wide range of economic programs that appear remarkably progressive, even by modern standards: Creating the Department of Agriculture, funding the transcontinental railroad, reforming monetary policy, and creating the first national parks and land-grant colleges. One policy, the Homestead Act, made millions of acres of government-held land available at very low cost. (For good measure, Lincoln made Thanksgiving into a national holiday for the first time.)

"His vision of the Union meant opportunity for all — hence homestead acreage for the many," Lincoln historian Harold Holzer told Salon about the 1862 Homestead Act during an interview last year. "It meant encouraging farming over hunting — independent farming to replace plantation aristocracies — hence [creating] the Agriculture Department."

Because the opposition party both literally and figuratively relinquished power, Lincoln and his party were granted a historic opportunity to change America — and seized it.

Just as important, most Republicans understood it was essential to hold the Confederate traitors accountable. Despite critics from moderate Republicans and Northern Democrats, Lincoln wanted to make sure that prominent Confederates would be barred from political office in the future. He was inclined to be lenient with rank-and-file rebel soldiers, while the so-called Radical Republicans favored a more punitive policy. But no one doubted there had to be consequences for people who took up arms against the government because they were unhappy about losing an election.

This brings us back to the present, and the historic passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which might not match the grandeur of Biden's original Build Back Better agenda, but still counts as the landmark achievement of his term and one of the biggest pieces of policy legislation in decades. Biden has had other achievements, as well as a number of obvious setbacks, but it would be ludicrous to suggest he comes anywhere near Lincoln's legacy. Arguably, he does face a similar problem in deciding how far to go in pursuing and prosecuting Donald Trump and supporters of the Trump insurgency. Whether or not Biden truly holds Trump and his enablers accountable is likely to determine how history views his presidency.

Shares