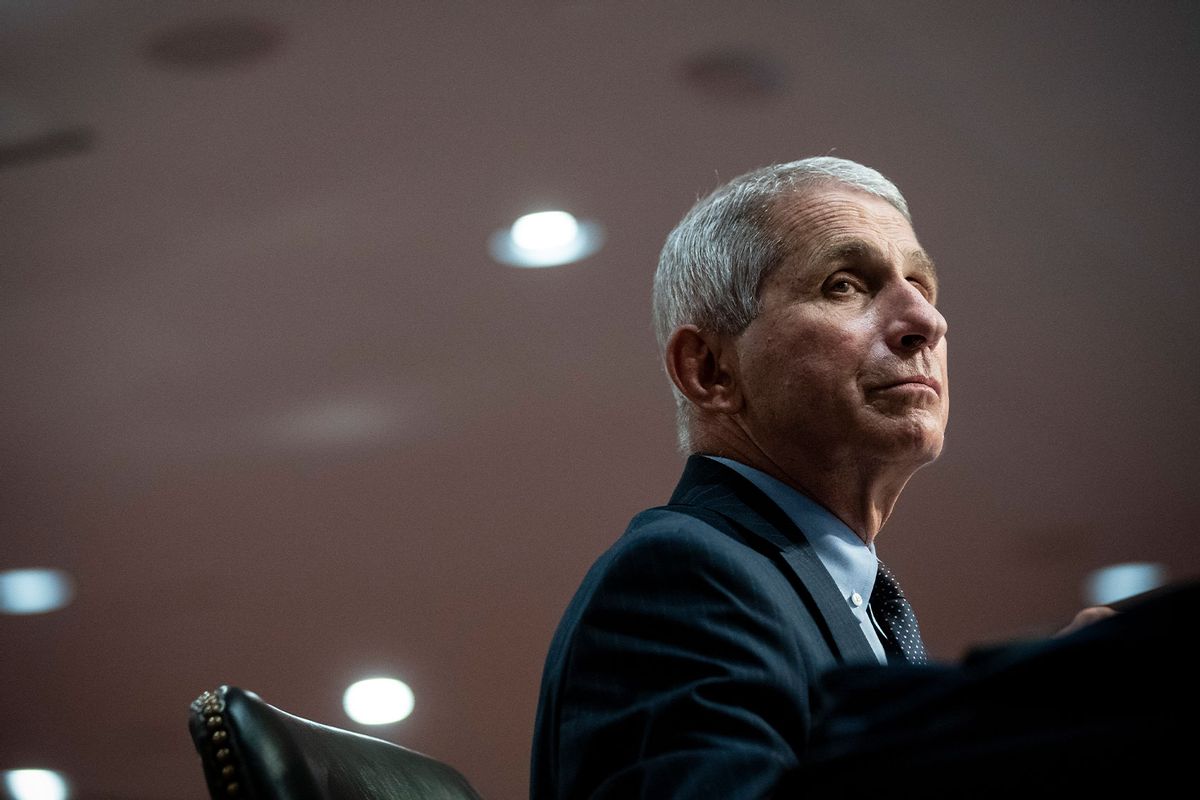

Several months after the COVID-19 pandemic arrived in the United States, Dr. Anthony Fauci shared an observation that proved to be oddly prescient. Speaking before the Aspen Ideas Festival, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases pointed out that "there is a general anti-science, anti-authority, anti-vaccine feeling among some people in this country — an alarmingly large percentage of people, relatively speaking."

Two years have passed since Fauci uttered those remarks. Now Fauci has announced that — after a career spanning back to the 1980s and including service under seven presidents — he is going to retire. Few physicians in the United States become household names; fewer still are remembered by historians, whether for positive or negative reasons. Regardless of one's opinion of the headline-making public health official, "Anthony Fauci" is a name that will be uttered for centuries by future historians of United States politics in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century.

Yet how history will remember Fauci is still not entirely clear. His legacy is multifaceted because it spanned different pandemics and epidemics (HIV/AIDS, COVID-19, and now monkeypox). History is still being written for many of those outbreaks, and decades may pass while data is collected and unintended consequences are inventoried. Until all of that work has happened, the full breadth of Fauci's legacy will not be etched in stone.

Salon reached out to a number of experts, both historians and fellow medical professionals, to gauge how history might remember the retiring physician. Intriguingly, two responses prevailed: First, that Fauci is a ubiquitous figure, with many top minds from the public health world recalling direct interactions with him; and second, that his leading role in shaping America's response to the COVID-19 pandemic — a task almost certainly made more challenging by the politically-charged backlash to which he alluded in Aspen — saved countless lives.

Whatever your opinion on Fauci's tenure, experts attested that the United States would be a very different place right now if Fauci hadn't been in power during the early years of the 2020s.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

"The most important priority for the National Institute of Health [NIH], and especially the National Institute for Allergies and Infectious Diseases, led by Dr. Fauci was the creation of a vaccine," said Dr. William Haseltine, the chair and president of the global health think tank Access Health International and a biologist renowned for his work in confronting the HIV/AIDS epidemic. "Nobody could have imagined it could have been done so rapidly, so fast. And so well in addition to that, not only did they develop the [COVID] vaccine — from a scientific point of view, they managed and conducted a global trial of the COVID-19 vaccine in, what I would say, is unimaginably rapid time."

Haseltine pointed to the years of foundational research done to develop HIV vaccines — research that was absolutely essential to developing the COVID-19 vaccines, and which was also led by Fauci.

Sommer described Fauci as having "acted exceedingly thoughtfully, and appropriately on multiple fronts: supporting the science as it evolved in his own NIAID division; and providing us with state-of-the-art health recommendations at every stage despite the political interference by the administration."

Though he was not a household name until the COVID pandemic, Fauci was a notable public health figure within the political and medical establishment long before that. Appointed by Ronald Reagan to lead the NIH in 1984, historians studying Fauci's legacy will have a lot of material to comb through before they focus on the last few years, when he had to take charge during the COVID-19 pandemic. Yet during that conflict, all agree that Fauci's most important job was to save lives — and all of the experts who spoke to Salon described those efforts as successful.

Perhaps that is why Dr. Monica Gandhi, an infectious disease doctor and professor of medicine at the University of California–San Francisco, was bullish on how Fauci will be remembered by future historians. Gandhi told Salon by email that "the vaccination program in the US likely saved many lives, in the US and around the world. Dr. Fauci, the FDA [Food and Drug Administration], the White House Task Force, and the CDC [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] oversaw the biggest mass vaccination program in the shortest period of time in the US with the COVID-19 vaccines and should all be commended for their incredible efforts."

On a personal note, Gandhi mentioned that she knows Fauci through her work "on the Advisory Council of [National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases], the organization he leads at the NIH," and described him as "a kind individual with a great interest in public health and doing the right thing when it comes to infectious diseases control."

Dr. Alfred Sommer, dean emeritus and professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, also told Salon that he knows "Tony" personally, including by chairing his periodic review for the NIH several years ago. Like Gandhi, Sommer highlighted how Fauci faced an extraordinarily difficult task when COVID-19 hit the United States.

"As you know, COVID arrived with little understanding from the medical, public health, and scientific community beyond what was learned during SARS-1," the preceding epidemic of related virus SARS in 2003, Sommer wrote to Salon. "That occurred over a decade ago and a version of the virus that was very different from this one."

Sommer described Fauci as having "acted exceedingly thoughtfully, and appropriately on multiple fronts: supporting the science as it evolved in his own NIAID division (which gave us one of the most effective and earliest vaccines); and providing us with state-of-the-art health recommendations at every stage, despite the political interference by the administration."

Not that Fauci didn't have his struggles.

Sommer noted that the Trump administration "often interjected and recommended absurd suggestions, which he was forced to deride despite the potential political attacks, and very personal threats of harm to him and his family." It was clear that this was an unusual dynamic, one that would make any responsible public health official's job more difficult, and yet Sommer notes that "as the virus changed, and the pandemic with it, [Fauci] kept us all informed about the implications and best advice for dealing with the changing nature of the pandemic as it was most rationally understood at the time."

"In many ways he emulated a role he has played throughout his career, at least at NIH where he has often been the person that we call 'the explainer of things,'" Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director of the American Public Health Association, told Salon. (Benjamin also personally knows Fauci.) "He would be the guy that would go out and explain to the public very complex scientific things." Benjamin observed that these skills, which Fauci began to hone in the 1980s, proved extremely useful by the 2020s. "I think at the end of the day his work both behind the scenes in terms of helping promote Operation Warp Speed, which got us a vaccine that was safe and effective in record time to save lives, and his ability to explain to people what was going on in a frank manner saved lives."

According to Dr. Joshua S. Loomis (who has not met Fauci personally), an assistant professor of biology at East Stroudsburg University and author of "Epidemics: The Impact of Germs and Their Power over Humanity," Fauci was given a tough hand and played it about as well as could be reasonably be expected.

"New studies are constantly yielding new data and fundamentally changing our understanding about individual infectious diseases," Loomis explained. "Fauci should have been praised for modifying protocols and recommendations to fit the most up-to-date information about COVID-19."

"Considering the enormous political pressure he was facing and the fact that he had no power to force individual state governors to abide by NIH/CDC recommendations, I think Fauci handled the COVID-19 pandemic as well as anyone could have in his position," Loomis wrote to Salon. "He shared up-to-date, complex scientific information with the public in a way that was clear and understandable. As new information about COVID-19 transmission and pathogenesis became available, he adjusted recommendations to fit that new data."

This was not always easy, as detractors would often criticize Fauci — out of ignorance if they were unaware of how science works, out of bad faith if they did — for supposedly "changing his mind" about public health recommendations.

"New studies are constantly yielding new data and fundamentally changing our understanding about individual infectious diseases," Loomis explained. "Fauci should have been praised for modifying protocols and recommendations to fit the most up-to-date information about COVID-19. Overall, I think he did an amazing job in his role as the public face of the COVID response, especially considering that his boss (Donald Trump) and several other politicians (e.g. Ron DeSantis, Rand Paul) constantly downplayed the severity of the pandemic and levied attacks against him personally and professionally."

Those personal and professional attacks didn't land, in large part, because Fauci had a long career of achievement in his field. If Fauci had retired in 2019 (before the pandemic reached America's shores), he still would have had an impressive legacy. Stewart Simonson, the Assistant Director-General of the World Health Organization, spoke to Salon by email about his work with Fauci during the crucial years after the Sept. 11th terrorist attacks.

"He was integral to every element of our biodefense and public health preparedness initiative," Simonson explained. "There is not a single success from that period—and there were many successes—that was not positively and significantly influenced by Tony. Actually, this is a bit of an understatement."

"We would not have MVA, the vaccine approved by the FDA to protect against monkeypox, without Project BioShield — and we would not have had Project BioShield without Tony Fauci. It is as simple as that."

Simonson pointed to the Project BioShield Act, passed in 2004, which included $5.6 billion in funding for countermeasures against chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear agents and special provisions like the Emergency Use Authorization, "which has been used extensively during the pandemic," Simonson noted. Simonson characterized Project BioShield as a forerunner to BARDA (the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, which was created in 2006 primarily to counter bioterrorism).

"I was part of the small group that drafted and lobbied the bill through Congress," Simonson explained. "But I honestly do not believe it would have happened without Tony's leadership. It would never have made it into the 2003 State of the Union speech let alone passed both houses of Congress had Tony not deployed his technical expertise, political capital and considerable powers of persuasion—many, many, many times."

Because of BioShield, Simonson told Salon, America is better prepared for biological threats like monkeypox; "indeed, we would not have MVA, the vaccine approved by the FDA to protect against monkeypox, without Project BioShield — and we would not have had Project BioShield without Tony Fauci. It is as simple as that. And that is but one relatively small element of his legacy."

Simonson also pointed to Fauci's crucial role in implementing PEPFAR (President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, a global program to fight HIV/AIDS launched by President George W. Bush). Simonson called PEPFAR "the greatest foreign assistance program since the Marshall Plan," and said that it "became the inflection point in the global fight against HIV because of Tony Fauci."

"He was intimately involved in it at every stage and the the very earliest discussions with Pres. Bush, Secs. Thompson and Powell—and then HHS, State, USAID and NSC staffs," Simonson said.. Fauci brought in international experts who could make sure that PEPFAR was effective once it began to be implemented on the ground, as well as used his credibility and persuasive powers to convince political leaders to support the program.

"The PEPFAR we know today — the program that has saved countless lives, alleviated suffering at the far corners of the earth and advanced our country's interests in so many ways — would not exist but for Tony Fauci."

Haseltine talked to Salon about his own experience with Fauci — which actually traces back to the start of Fauci's career in Washington.

"Since he was appointed in 1984, I was a member of his council," Haseltine told Salon. "I worked with him in lobbying Congress. I worked with him on strategies for the treatment prevention of HIV/AIDS and many other diseases. Tony was a very active and involved as a leader, both as a researcher and as a global leader for control of pandemic diseases."

Like Simonson, Haseltine pointed to Fauci's work with George W. Bush in fighting the HIV pandemic in Africa, stating that "Tony was instrumental in saving tens of millions of lives throughout the world, most predominantly in Africa where the HIV pandemic was most pronounced."

While Fauci's AIDS work through PEPFAR is widely praised, he was a focal point of criticism from the LGBTQ movement during the '80s because he oversaw the NIH during the AIDS epidemic of that decade. Yet even there, many of Fauci's contemporaries feel he did a good job.

"This was Tony's first real trial by fire. My short answer: he did a remarkable job!!" Sommer wrote to Salon. He praised Fauci by noting that although "a lesser person would have both been angry, recalcitrant, and quit" by the criticism from the LGBTQ community and other activists invested in drawing more attention to the HIV/AIDS crisis; he argued that Fauci did the best he could with the resources he had. Fauci "listened, heard and understood their 'pain' (even as they made him the whipping boy for their own fears and frustrations), and actively embraced and worked with them."

Gandhi also praised Fauci's handling of the AIDS crisis. "I think he managed the AIDS pandemic extremely well and so much happened under his watch. He was always willing to learn from activists – like Larry Kramer — and oversaw a highly successful campaign on HIV."

Yet Gandhi was not reluctant to criticize Fauci on other issues.

"Our vaccine uptake in the United States was not as high as other high-income countries, leading to avoidable deaths in the U.S," Gandhi wrote to Salon, citing a piece she wrote in February 2021 for Leaps Magazine advocating optimistic messaging about vaccines early on to promote uptake.

"He was integral to every element of our biodefense and public health preparedness initiative," Simonson explained. "There is not a single success from that period—and there were many successes—that was not positively and significantly influenced by Tony. Actually, this is a bit of an understatement."

"I think the White House's confusing messaging on the need to mask after vaccination and that life does not go back to normal negatively affected vaccine uptake," Gandhi argued. She pointed to countries like Denmark and Switzerland that had messaged more optimism regarding vaccines, in particular stressing that they could bring people back to their normal pre-pandemic lives more quickly.

"Although I was an early supporter of masks, mask mandates didn't seem to make much of a difference in the US," Gandhi told Salon. "I think Dr. Fauci and other public health officials should have been more motivating about the power of the vaccines to restore normalcy, and that is my main criticism of the response."

One might wonder if these so-called errors — if one perceives them this way — would have happened regardless of who was in charge. Even among scientists who are all acting in the best of faith, there will always be sincere and unavoidable disagreements. No public health official can avoid entirely controversy, and perhaps it would be unwise for them to even try. Yet the bottom line is that, whatever mistakes he made, Fauci was never incompetent, malicious or corrupt. The consensus view is that he was a doctor who genuinely tried his best to help people — whether it was an entire nation under siege by a virus, or a single patient that desperately needed compassion.

Simonson shared an anecdote that captured the flavor of the rest.

"Several years ago, I was at the NIH Clinical Center (the research hospital in Bethesda) working on a project, and I bumped into Tony on rounds," Simonson recalled. "He was outside the room of [a] patient with some awful undiagnosed condition that had destroyed his immune system. It wasn't HIV or anything they had seen before. And the poor soul was just mutilated — or so I was told. I did not go into the room for obvious reasons."

At that point, Fauci decided that the patient's final hours of life should be spent with as much dignity as possible.

"The total focus of the consultation that morning was how to give this patient some quality of life for the time he had left," Simonson recalled about Fauci. "There was no longer any talk of the research protocol or what could be learned from him or his disease. It was all about giving him some dignity and something to make his life worth living. This consultation went on for a long time — someone would come-up with something, and Tony would send for the expert if the person was on campus or, if not, arrange a call. It was more like a meeting of GPs, social workers and chaplains than biomedical researchers. It moved me then as it does now."

"And that is his legacy to my way of thinking," Simonson concluded. "Whether on the wards, at HHS [Health and Human Services], the White House or on the Hill, Tony has devoted his life as a physician-scientist to easing suffering, saving lives and advancing the frontiers of knowledge. And no one has done it better."

Shares