Future historians may well remember 2022 as the year when the U.S. Supreme Court permanently went off the rails. This goes well beyond the tormented, quasi-religious reasoning used by the court's conservative majority in Dobbs v. Jackson, the case that officially reversed the nationwide abortion rights established in 1973 by Roe v. Wade. In the course of revoking women's reproductive rights, the justices also hinted they might reverse the right to same-sex marriage, and perhaps even the right to contraception. Perhaps even more consequential, the court also decided it would hear Moore v. Harper, a North Carolina case about whether state courts may strike down gerrymandered congressional maps. If the conservative majority buys into the dubious legal theory known as the independent state legislature doctrine, it will effectively empower Republican-dominated state legislatures to overturn the popular vote in future presidential elections.

Roosevelt told the nation the Supreme Court had "improperly set itself up as a third House of the Congress — a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it — reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there."

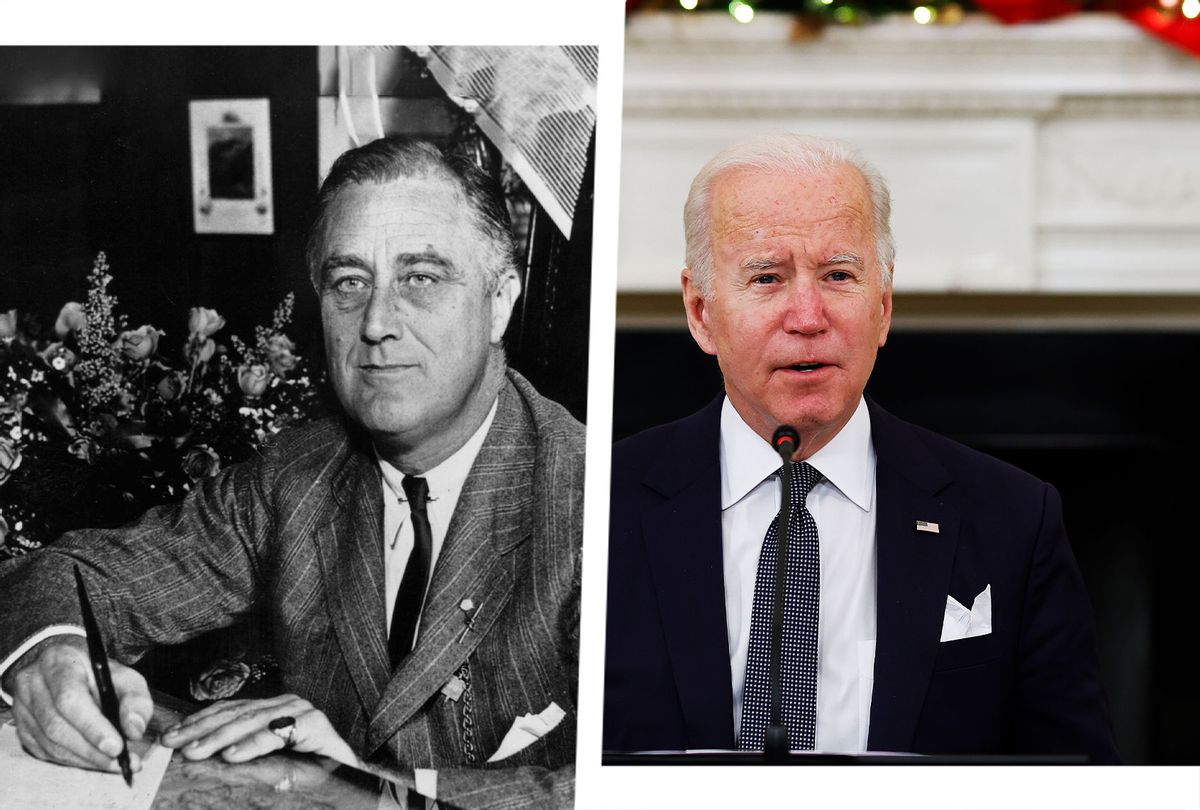

If it seems like the Supreme Court is determined to impose an extreme right-wing agenda on the rest of the country, you should know that this isn't the first time. Indeed, when conservative judges went on a similar radical rampage in the 1930s, Franklin D. Roosevelt fought back with the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937. Among other things, it allowed the president to appoint a new Supreme Court justice for every sitting justice over age 70, up to a maximum of six extra justices in total. (The Constitution doesn't specify the number of Supreme Court justices, which Congress set at nine in 1869.)

That will sound like a fantastic idea to many Democrats and liberals in 2022, but it was viewed as wild-eyed radicalism 85 years ago. Derisively dubbed the "court-packing plan" — probably the first appearance of that term in political discourse — FDR's reform bill was perhaps his biggest single failure, and almost single-handedly derailed his ambitious domestic agenda. Ever since then, the memory of that political catastrophe has been powerful enough that presidents of both parties never even considering court-packing. Only the court's recent hard-right shift, along with what could reasonably be called the Republican version of court-packing — exemplified by blocking the confirmation of Merrick Garland in 2016 and then rushing through the confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett in 2020 — has begun to change that dynamic.

To understand what drove Roosevelt to try to "pack" the Supreme Court in the first place, we first have to consider a quartet of reactionary judges determined to stymie his agenda, who were dubbed the "Four Horsemen" by the pro-FDR press.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

These four justices — Pierce Butler, James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland and Willis Van Devanter — were profoundly hostile to Roosevelt's New Deal programs and did everything they possibly could to stop them. After taking office in 1933 at the depths of the Great Depression, Roosevelt spent much of his first term passing bills to create a safety net of economic security for vulnerable Americans, most of which simply hadn't existed before that. This included federal employment programs that created millions of jobs, the universal pension we now know as Social Security and a number of laws to protect labor unions and regulate big businesses. Roosevelt's overall goal was to achieve what future scholars would call the "3 R's": relief for the poor, recovery for the economy and reform of a financial system that was so corrupt it had brought the economy to its knees.

While the conservative Supreme Court justices privately grumbled about the New Deal practically from Day One, they were astute enough to understand that it might be disastrous if they tried to block FDR's entire legislative agenda. There were serious fears that the widespread suffering and mass unemployment of the Great Depression might inspire a socialist revolution, and even hardened conservatives understood that some relief measures were necessary, if only to cool the national temperature.

FDR's court-packing gambit was a disastrous failure: He was never again able to pass the kind of ambitious reform legislation he had during his first term.

By 1935, however, the Four Horsemen felt that their moment had arrived. Determined to outvote the trio of liberal justices known as the Three Musketeers — Harlan Stone, Louis Brandeis and Benjamin Cardozo — the Horsemen recruited the court's two moderates, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes and Justice Owen Roberts, to join in their judicial coup. In short order, several key Roosevelt and Roosevelt-supported initiatives were found "unconstitutional" for a convenient variety of reasons, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the Federal Farm Bankruptcy Act, the Railroad Act, the Coal Mining Act and even a New York law establishing a minimum wage for women and children. The Four Horsemen made no secret of their opposition to Roosevelt, and openly boasted that they intended to thwart any and all restrictions on business and commerce, protections for labor unions or precedents that the state should take measures to alleviate poverty. The Horsemen even rode to and from work together in the same chauffeured car, making it even more obvious that they were coordinating their political and legal strategies.

None of this was a secret to the public or the media, yet when Roosevelt tried to fight back directly with the Judicial Procedures Reform Bill, the whole thing blew up in his face. Even though FDR had been re-elected by an unprecedented landslide majority in 1936, he was suddenly faced with widespread rebellion within his own party. Even his political allies saw the proposed bill as an attempt to violate the supposedly apolitical nature of the Supreme Court. It didn't help that Roosevelt was initially less than forthright about his motives, claiming that his primary concern was the justices' advanced age, not their ideology. That was clearly untrue, which likely soured the public against the entire idea by the time he made the real case — which, in his defense, was also the logically and morally sound one — in a national address:

The Court in addition to the proper use of its judicial functions has improperly set itself up as a third House of the Congress — a super-legislature, as one of the justices has called it — reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there, and which were never intended to be there.

Despite that unassailable logic, the court-packing gambit was a disastrous failure. First the bill was bottled up by an alliance of Republicans and conservative Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee, and then it became politically moot when Justices Roberts and Hughes — the court's two moderates — switched sides on the landmark minimum wage case, West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish. (Some observers claimed that Roberts changed his position in direct response to the court-packing threat, but subsequent scholarship has established that wasn't the case.) Roosevelt's popularity nosedived, and Democrats suffered major losses in the subsequent 1938 midterms.

FDR recovered from the debacle well enough in his own career, and was even elected to unprecedented third and fourth terms, remaining president until his death in 1945. But the political damage was real: He was never again successful in passing the kind of ambitious reform legislation he had during his first term. He was ultimately able to appoint his own majority to the Supreme Court simply due to the passage of time, but was never enable to enact the full agenda outlined in his 1944 Economic Bill of Rights. Conservatives had learned the secret to defeating him, a formula that endured until very recently: Forge a bipartisan alliance between pro-business Republicans and racist Southern Democrats (who would soon enough become Republicans themselves), then exploit the fear of "socialism" to convince much of the public that even modest liberal reform ideas were dangerous and un-American.

Still, it's not fair to assume that Roosevelt's failure to expand the Supreme Court means that the idea is intrinsically toxic. If FDR had been upfront about his reasons from the beginning, he might well have convinced his liberal allies to go along, since many of them shared his frustrations with the reactionary justices. So far, Joe Biden appears reluctant to consider a court-packing push, especially facing a midterm election that threatens his fragile majorities in both houses of Congress. But given the nature of the current Supreme Court, the question that will surely face Biden (or some future Democratic president, if there is one) is not whether court-packing is historically or morally defensible, but simply how to make it happen.

Shares