A string of recent election results — including the Kansas abortion amendment and special elections for House seats in New York and Alaska — make it clear that the Supreme Court's decision overturning Roe v. Wade has enormous political consequences, and could even end up preserving the Democrats' hold on Congress this year. But the court's decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization wasn't the only earth-shaking break with precedent in the last two weeks of its term. Even if Democrats do hold onto Congress and somehow codify Roe into law (an unlikely set of outcomes) that would only affect one aspect of the vast sweep of policy change the court's rulings portend.

The new book by UC Berkeley Law School dean Erwin Chemerinsky, "Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism," shows how fundamental those changes could be and focuses on the bogus legal reasoning known as "originalism," which plays such a crucial role in justifying this sudden and sweeping assertion of judicial power.

Originalists claim to be guided by the original meaning of the Constitution and argue that everyone else is swayed by their own subjective values in groping for other kinds of reasoning. Chemerinsky, as it happens, has first-hand experience in drafting a constitution of sorts. He chaired the Los Angeles Charter Commission, an elected body that rewrote the charter for the second-largest city in the U.S. (in collaboration with a parallel appointed body) just over 20 years ago. So his argument that originalists' key claims about constitutional meaning are simply false carries significant weight. Even while writing the L.A. charter, Chemerinsky says, there often wasn't one unanimously agreed-upon meaning for its specific language, and that was even less true after the fact. Over the course of the last 20 years, he reports, questions have arisen that weren't even considered in the drafting process.

There's considerable evidence that the same was true of the Constitution written in Philadelphia 235 years ago as well, but none of the framers are still around to confirm that. Chemerinsky doesn't use his personal experience as the central argument of his book, but it clearly underscores the gap between the sweeping claims made by originalists and the granular, often difficult-to-discern nature of constitutional reality. That should make all of us willing and eager to seek understanding from a variety of different approaches and points of view. which is what the vast majority of judges have done throughout most of our constitutional history.

Much of Chemerinsky's book is devoted to explaining the five biggest problems that originalists face, any one of which is arguably fatal to their dogmatic claims. The argument mentioned above is part of the epistemological problem, meaning the impossibility of finding a single fixed meaning that simply does not exist. What's just as bad is the abhorrence problem, meaning that sometimes the original meaning of the Constitution is clear enough, but the results of an "originalist" interpretation would be morally abhorrent to most Americans today. Then there's the incoherence problem: If originalism is the correct approach, then originalism itself must be written into the Constitution. But it isn't, and Chemerinsky concludes that the only true originalist position, paradoxically or otherwise, is to reject strict originalism.

Chemerinsky explores these and two other problems in five central chapters of his book, while also providing a historical introduction and a discussion of why originalism is attractive to so many conservatives. Ultimately, he argues forcefully for an alternative view, a more pluralistic approach that seeks understanding from different sources, as judges have been doing for hundreds if not thousands of years. He concludes with a reflection on the dangers that originalism poses to the rights and freedoms that Americans today have come to cherish or, perhaps foolishly, have taken for granted.

This transcript has been edited for clarity and length.

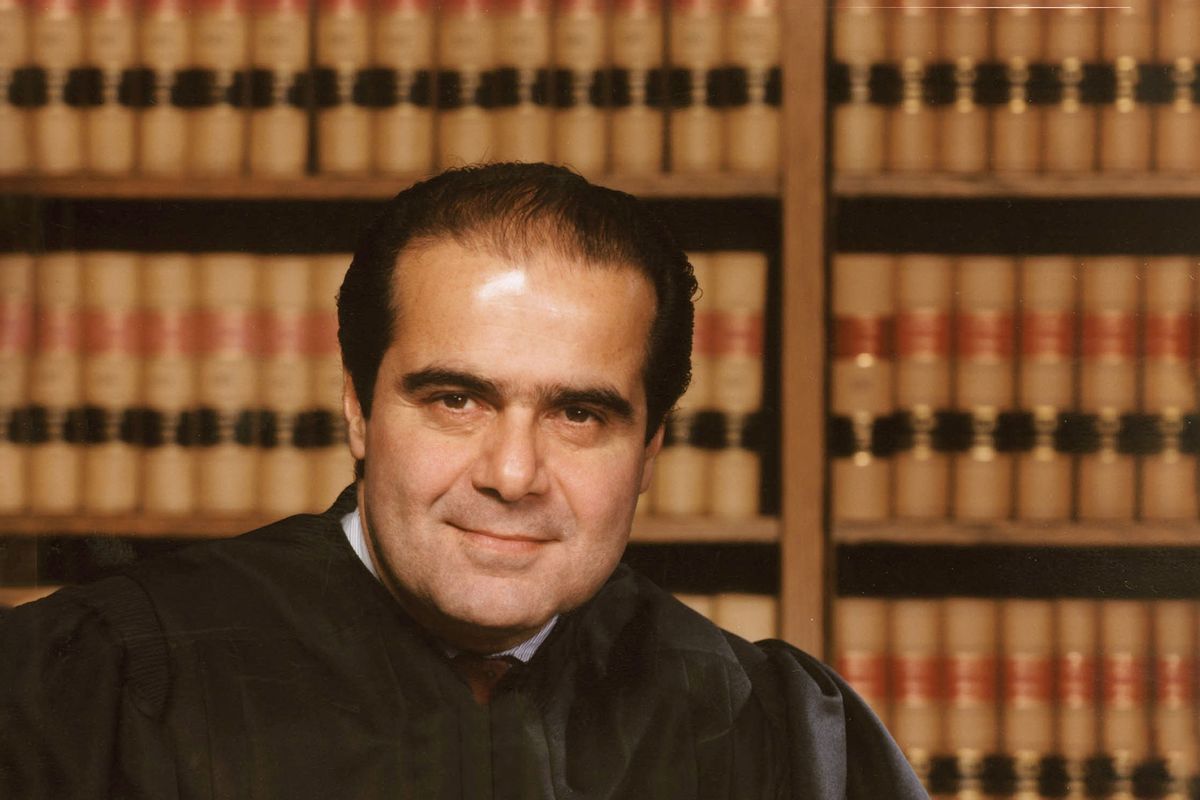

The title of your book, "Worse Than Nothing," is a direct response to Justice Antonin Scalia's claim that whatever the faults of originalism's faults may be, he had a theory, while the critics of originalism had nothing. Before digging into the details, what's your bottom-line response to this claim?

As the title suggests, I think originalism is a very dangerous approach to constitutional law, and in this instance I think it really is worse than nothing.

The core of your book lays out five key problems with originalism, but you begin by describing its rise in the first chapter and its allure in the second. What drove that rise and how did it proceed?

In large part it was the conservative political movement that drove originalism. The Federalist Society embraced originalism, and nurtured a belief in it. Also, I think it was simply about who has won elections. If Hillary Clinton had won the presidency in 2016 and if she had replaced Justices Scalia, Kennedy and Ginsburg, we wouldn't be talking about originalism today. It would be a fringe theory on the Supreme Court that a group of conservative law professors kept alive. But Trump appointed three conservatives, joining conservatives who were already there, and that is causing originalism to be in the ascendancy.

Why is originalism worrying, and how does this echo the 19th-century dominance of the legal doctrine known as "formalism"?

I think it's a simplistic theory. It says, "We don't want judges to impose their own values. We want judges to discover the law and mechanically apply it." That's formalism, which has always had an intuitive appeal, because it seems to take out of decision-making individual biases, preferences and ideology. So originalists say, "We're going to discover the original meaning of the constitutional provision and apply it. These other people are all making it up, imposing their own values."

The first of the key problems you tackle is the epistemological problem. You begin by talking about your experience as chair of the elected L.A. Charter Commission. How did that experience illuminate the problem of determining meaning in the Constitution?

Some scholars have persuasively argued that the framers of the Constitution didn't believe in originalism, and therefore if one is to follow the framers' intent or the original understanding, one has to abandon originalism.

A charter for a city in California is much like its Constitution. It creates the institutions of government, it allocates power and it even provides more protection of rights than exist under federal or state law. I went through the two-year experience of chairing a commission to draft the charter and inevitably, issues of interpretation arose. They came up soon after the charter was adopted, and they continue to arise now. Just yesterday I got a memo concerning certain issues in the Los Angeles charter that are much in the news. What I have discovered was that, almost always, the issues that are arising now are ones that we didn't consider then, even though the "then" was very recent. And when we did consider them, there was a difference of opinion about what we intended and what we meant.

The reason this informs me is that, if we couldn't decide the original meaning of the charter right after it was adopted, when all the commissioners were then still alive, how can we do so for a constitution that was written in 1787?

One of the key problems in establishing "original meaning" is the level of abstraction. How does shifting the level of abstraction change the meaning?

If the original meaning of the constitutional provision is stated at a very abstract level, then any result can be justified. At the most abstract level, the Constitution is about liberty and equality, separation of powers. But the constraint that originalists purport to get is gone when the original meaning is stated in a very abstract way. On the other hand, if we focus on the original meaning at a very concrete and specific level, then the Constitution becomes unacceptable. Then Brown v. Board of Education [on school desegregation] was wrongly decided, Loving v. Virginia [on interracial marriage] was wrongly decided.

In Chapter 4, "The Incoherence Problem," you argue that there's no indication the Constitution meant to create judicial review, much less originalist judicial review, and in fact that there's evidence to the contrary. So an originalist reading actually requires abandoning originalism. Can you elaborate on that?

An originalist would say that all aspects of the Constitution are to be determined by its original meaning. That would have to include the question of whether there should be the power of judicial review at all. In fact, the text of the Constitution says nothing about the power of judicial review, and it wasn't explicitly discussed at the Constitutional Convention. It would seem, then, that from an originalist perspective there shouldn't even be judicial review. But if there is judicial review, then how, from an originalist's perspective, should courts go about interpreting the Constitution? Scholars such as Jeff Powell at Duke have, I think, persuasively argued that the framers of the Constitution didn't believe in originalism, and therefore if one is to follow the framers' intent or the original understanding of the Constitution, one has to abandon originalism.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In Chapter 5, "The Abhorrence Problem," you focus on three repugnant results of originalism: If we go by clear and original intention, then segregation and racial discrimination generally are permissible, for example, and the First Amendment allows government to prohibit blasphemy and seditious libel. I'd like to focus on the first example. because it involves the landmark case of Brown v. Board of Education. You quote from Chief Justice Earl Warren's opinion, which explicitly rejected originalism. Talk about the originalists' problem with the Brown decision — how they try to deal with it and how they fail.

The central problem with Brown, from an originalist perspective, is that the result can't be justified under originalism. The same Congress that voted to ratify the 14th Amendment also voted to segregate the District of Columbia public schools. There's no indication whatsoever that Congress, in proposing the 14th Amendment — or the states, in ratifying it — saw it as outlawing segregation. Brown v. Board of Education was first argued to the Supreme Court in the October term of 1952. The justices couldn't come to a decision and asked for re-argument, focusing on the intent of the framers with regard to segregation. Those briefs were filed, the case was re-argued and then Chief Justice Warren, writing for the unanimous court, said, "We can't focus on originalism, we can't turn the clock back. Education plays a far different role in society today than it did in 1868."

From an originalist perspective, the result of Brown v. Board of Education can't be justified. There's no indication whatsoever that Congress saw the 14th Amendment as outlawing segregation.

Originalists try to get around this embarrassment in some ways. They try to state the goal of equal protection at an abstract enough level that Brown becomes permissible — but then originalism becomes indistinguishable from non-originalism. There's another attempt at this: The most famous one is by Stanford Law professor Michael McConnell in the Virginia Law Review, where he points especially to a statute adopted in 1875 that outlawed segregation. There are many problems with McConnell's approach. As he himself concedes in the article, there's no evidence that when Congress ratified the 14th Amendment, it meant to outlaw segregation. Also, 1875 is not 1868, when the 14th Amendment was adopted. There's no reason to believe that what they did in adopting a statute in 1875 is the same as what they meant to accomplish with a constitutional provision.

In chapter 6, "The Modernity Problem," you highlight three issues. Two of those deal with specific kinds of technological development — surveillance and communication — and one is much broader, the question of how the country's growth in size and complexity changes how it must be governed. Can you address both of those? Pick one of the technological developments to talk about and then take up the broader problem of growth, and explain how originalism fails to deal with these developments.

When the Constitution was ratified and the Fourth Amendment was adopted, it was thought that a search required a physical intrusion by the police. When the Supreme Court first defined a search, it wasn't until 1928, in Olmstead v. U.S., when the court said that wiretapping was not a "search" if it's done without going on somebody's premises. That makes no sense in terms of the current methods of police gathering information.

One of the most important recent Fourth Amendment cases was Carpenter v. U.S. in 2018, where the police obtained 127 days of cellular location information about a person and used it as key evidence in a prosecution that led to a sentence of 100 years. There was no physical trespass on a property, but it was an enormous invasion of privacy. When we look at other technology that exists now for police to accomplish searches — drones, surveillance airplanes, cameras on utility poles that monitor was going on 24 hours a day, seven days a week — it makes no sense to think of the Fourth Amendment solely as about physical trespass. The Supreme Court found in Carpenter that obtaining that cellular location information was a search, but Justices Thomas and Gorsuch, who are originalists, said it should take an invasion of property rights to count as a search. That just doesn't make sense when the government now can gather so much information without a physical trespass.

In terms of the growth in the size of the country, the United States in 1787 was 13 states. There was nothing like the methods of transportation or communication that exists today, so there could be a very small federal government. But in our modern technological world, the country spans the continent and includes territory as far away as Guam and Saipan. We need a government that has the tools to be able to deal with this. So the Thomas approach, which would radically limit federal government power, makes no sense in the current world.

Expansion of the federal government dates back to the 1870s, at least. How has that balance changed over time and how has the reasoning about it shifted?

The size of the federal government has dramatically expanded as the country has expanded, as technology has developed, as the problems become more complex. In 1787, the framers wouldn't have thought of the need to have an Environmental Protection Agency to deal with the problem of pollution or greenhouse gas emissions. Today, climate change and greenhouse emissions, imperil human life on the planet. So we need a government that is has the tools to deal with the problems that we face. Unfortunately, the conservatives on the court, following originalism, have a very narrow view of congressional power. Justice Thomas, especially, would greatly limit the federal government's authority to deal with key social problems.

You write about the court striking down regulation during the New Deal, and then doing very little of that for generations, until just recently. What can we learn from that history?

The Supreme Court declared some key New Deal legislation unconstitutional for delegating too much power to the executive branch. The last time the Supreme Court invalidated a federal law as an improper delegation of power was in 1935. Now I think we have a majority on the court that wants to revive the non-delegation doctrine. They've also created something new called the "major questions" doctrine, saying that an agency can't rule on a major question of economic or political significance unless Congress gives clear direction. This is a sibling to the non-delegation doctrine. In fact, on June 30, 2022, in West Virginia v. EPA, the Supreme Court limited the EPA's power to regulate emissions from coal-fired power plants, using the major questions doctrine.

In Chapter 7 you deal with the hypocrisy problem, meaning that conservatives abandon originalism when it doesn't suit their purposes. Because of its central importance, I'd like to focus on the invalidation of the Voting Rights Act, which was not grounded in original intent or meaning. How do you explain what happened?

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was one of the most important laws adopted in my lifetime. It dealt with pervasive, long-standing disenfranchisement of voters of color, especially Black voters. In section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, it prohibits state and local governments from election practices or systems that discriminate based on race. But Congress knew that authorizing lawsuits to challenge race discrimination wouldn't be sufficient. Congress was aware that Southern states kept changing the voting practices to disenfranchise minority voters, and decided to create a preventative mechanism. Section 5 of the act said that jurisdictions with a history of race discrimination in voting had to get pre-approval or "pre-clearance" from the attorney general or a three-judge federal court before changing their election system.

Chief Justice Roberts said the Voting Rights Act violated the principle of "equal state sovereignty." But where is this found in the Constitution? Nowhere.

This provision was tremendously effective. There were hundreds of instances where pre-clearance was denied and there were thousands where state or level governments didn't even try because they knew they wouldn't get pre-clearance. This was enacted and upheld as constitutional, and when it was scheduled to expire it was re-enacted in 1982 for another 25 years. Then, when it was scheduled to expire in 2007, Congress held over 15 hearings and compiled a legislative history of over 10,000 pages documenting a continued need for pre-clearance. Congress then extended pre-clearance for another 25 years. It passed the Senate 98-0. There were only 33 "no" votes in the House. George W. Bush signed it into law.

But in Shelby County v. Holder in 2013, the Court declared the pre-clearance law unconstitutional. What constitutional principle or provision did the Voting Rights Act violate? Chief Justice Roberts said it violated the principle of "equal state sovereignty," which holds that Congress must treat all states alike. But where is this found in the Constitution? Nowhere. It doesn't say that. In terms of original meaning, the same Congress that ratified the 14th Amendment also voted to segregate the District of Columbia public schools. In fact, the same Congress that ratified the 14th Amendment imposed military rule on Southern states, showing it didn't believe in equal state sovereignty.

After laying out all those arguments, you move into a threefold affirmative defense of non-originalism. I'd like to ask you to elaborate a bit on each of those arguments. The first one being that a pluralist epistemology is desirable.

My argument is that throughout American history, the Supreme Court has looked at many sources. Of course it looks at the text of the Constitution, it always was looking at the original meaning. It should look at history, look at precedents, look at modern social needs. I think to ignore any of those is undesirable. Why believe that all wisdom stopped in 1787, when the Constitution was adopted? Or when the Bill of Rights was adopted? Why not believe that there is wisdom to be gained from all of these different sources? That's my argument: It's desirable for the court not to be limited just to historical original meaning.

Your second argument is that a living Constitution that evolves by interpretation as well as amendment is desirable.

I think a preeminent purpose of the Constitution is to safeguard minorities of all sorts. Yet I think it is very difficult for the Constitution to do that unless there is evolution by interpretation. We shouldn't require a supermajority to protect the rights of minorities. Let me give you an example. We've already talked about Brown v. Board of Education, which would not have been decided in the same way under originalism. Loving v. Virginia, where the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional state laws prohibiting interracial marriage, wouldn't have been decided the same way under originalism. Using the Constitution to combat sex discrimination wouldn't work under originalism. Using the Constitution to combat sexual-orientation discrimination — the right to marriage equality for gays and lesbians — wouldn't work that way under originalism. It makes no sense to me to say that those changes can happen only through the amendment process. Then you're saying a minority can be constitutionally protected only if it has a supermajority behind it.

Finally, you argue that candor and transparency in constitutional decisions are desirable.

I think what originalists do is to impose their conservative values and then hide behind the originalist rhetoric to claim that they're just following the original meaning. I think that conservatives, as much as liberals, are imposing their values on constitutional decisions. Consider the cases in June of 2022. The book was finished in the summer of 2021, so it doesn't cover these. But the conservatives on the court found that there's no constitutional right to abortion, that there's very broad protection of gun rights, that there is a right of teachers to pray at high school football games and that the state is obligated to support parochial school education in certain circumstances. All of that is consistent with current Republican conservative ideology. It's not that the framers of 1787 to 1791 thought the same way as the current Republican Party. Conservatives are just imposing their values.

So what I say is: Let's all be transparent. Let's acknowledge that the court is making value judgments. No one should hide behind the guise of originalism.

It strikes me that all these arguments are important, because without honest argument, everything else is suspect. You frame it as "candor and transparency," but at bottom isn't it simply about honesty?

Yes. I think there is a dishonesty, a disingenuousness, in conservatives pretending that they're just following the original meaning and not making value choices. They're making value choices just as much as any liberal justice would.

Chapter 9 is titled "Why We Should Be Afraid." You focus on three areas where dramatic changes should be expected from originalist judges. Say a little bit about each of those. The first area is about rights of privacy and autonomy.

Originalists are imposing conservative values and hiding behind their originalist rhetoric. ... What I say is: Let's all be transparent. Let's acknowledge that the court is making value judgments.

As I mentioned, I finished the book in the summer of 2021. What I predict in the book that given the originalist views of the court in the conservative justices, that the court would overrule Roe v. Wade. It did that on June 24 in the Dobbs decision, where Justice Alito said that a right should be protected under the Constitution only within the text, part of the original meaning or to safeguard a long unbroken tradition. Justice Thomas wrote a concurring opinion in which he said the court should now overrule Griswold v. Connecticut, which allowed purchase of contraceptives; Lawrence v. Texas, which established the right of consenting adults to engage in private same-sex sexual activity; and Obergefell v. Hodges, where the court found a right to marriage equality for gays and lesbians. I think if one follows an originalist view, that is the conclusion. All of these rights protecting privacy and autonomy are endangered.

The second area concerns the scope of congressional power.

Originalists like Justice Thomas believe the federal government has very limited authority, but that doesn't work in the world of 2022. We need the federal government to be able to deal with things like air pollution and climate change, or technology. I worry that what we're going to see from the conservative justices is significant constraints on federal power to deal with urgent social problems.

Finally, the third area is about the Constitution's religion clauses.

Again, I finished the book in the summer of 2021, but I predicted you'd see aggressive protection of free exercise of religion. And we saw it at the end of June 2022 in Carson vs Makin, where the Supreme Court said that whenever the government gives aid for private secular education, the government is constitutionally required, even mandated, to provide that aid for religious education. The court said in Kennedy v. Bremerton Schools that a high school football coach had the First Amendment right to go onto the field after games and engage in prayer, even when joined by teammates and members of other teams. I think we're going to see in the next term rulings on the ability to violate anti-discrimination laws, based on free speech and religion.

Given all of the above, what conclusions do you draw about how the public should respond? What do we do?

I think it's important to see, when it comes to the Supreme Court, that it's an emperor with no clothes. It's a conservative court, it's conservative justices imposing their conservative values. It's not about originalism at all. They write opinions in terms of originalism, but we should see that as the fig leaf to cover what's really going on — conservative justices imposing conservative values.

It seems that you have a pluralistic approach to law, and to epistemology as well. You argue that there's no one right way to do things, no determinate outcome, but that a tradition can evolve out of diverse views coming into conflict with with some kind of self-regulation. That pluralism seems inherent in a liberal as opposed to conservative view of the nature of human knowledge and law. Do you have any broader thoughts about that?

Let me take an example. The Second Amendment says, "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed." Do gun control laws violate that? If the government says that people need a concealed weapons permit, or if the government prohibits handguns, does it violate that? It depends on how you want to read the Second Amendment. If you read it as primarily about militia service, then those government regulations are allowed. If you read it as being about the right of individuals to keep and bear arms, those regulations aren't allowed. There's not an inherently right or wrong answer to the question. It's a choice.

It shouldn't surprise us the conservatives who embrace gun rights strike down gun control laws and liberals who favor gun control would uphold those laws. It's not about neutral methodology, but value choices by who's on the court. Virtually all constitutional provisions get litigated. There are arguments on both sides, and it's a mistake to think there's a right answer out there, waiting to be discovered.

I always like to end by asking: What's the most important question that I didn't ask? And what's the answer?

I think the most important question to ask is: What should we expect in the future? It's likely we're going to have a Supreme Court that is highly originalist for a long time to come. You look at the conservative justices: Clarence Thomas is 74, Samuel Alito is 72, John Roberts is 67, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett are all in their 50s. So the rise of originalism that we've seen on the Supreme Court is likely to be followed for many years to come.

Doesn't this argue for the need to think about court expansion and other possible reforms, such as term limits? Elie Mystal of the Nation has suggested expanding the Supreme Court to the size of a district court, so you have a panel system that would decentralize its power.

I favor expanding the size of the Supreme Court. I think the current court is a result of Republican court packing — blocking Merrick Garland and rushing through Amy Coney Barrett. I think we're not going to see an expansion in the size of the Supreme Court, because we know Republicans would filibuster that in the Senate and there aren't the votes among Democrats to remove the filibuster.

I favor 18-year nonrenewable terms for justices. Too much depends on the accident of history and when vacancies occur, and life expectancy is a lot longer now than it was in 1787. Clarence Thomas was appointed to the court in 1991 when he was 43 years old. If he stays on the court until he's 90, he'll be a justice for 47 years. Amy Coney Barrett was 48 when she was confirmed. if she stays on the court until she's 87, the age that Justice Ginsburg was, she will be a justice until 2059. It's just too much power in too few people's hands for too long a period of time. But I don't think we're going to get 18-year term limits. I believe it would take a constitutional amendment and I don't see a constituency that cares enough to do the work.

I would oppose having a court with panels deciding cases. We have too much of a need for consistency and resolution, and I think when you have panels inevitably they disagree with one another. It would cause chaos.

Shares