Tens of thousands of people lack access to housing in California. Streets strewn with tents have become ubiquitous across the state as the cost of living rises and wages stagnate. For months, California Gov. Gavin Newsom has been touting a solution: forcing unhoused people with mental health conditions into treatment.

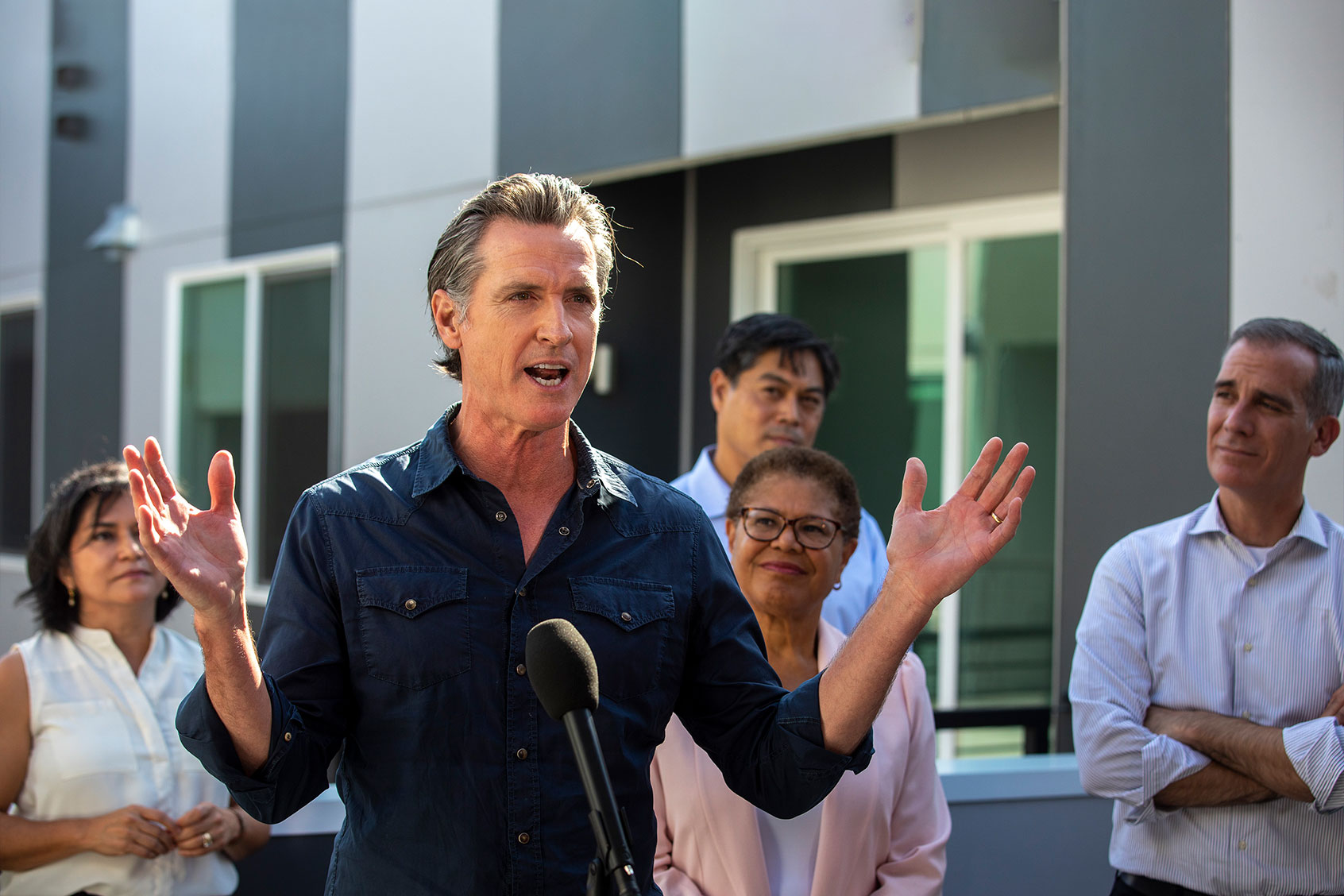

While some groups have opposed this plan since its conception — including Disability Rights California, the American Civil Liberties Union of California, the Drug Policy Alliance and Human Rights Watch — they were unable to stop its passing. On Wednesday, Sept 14, Newsom signed SB 1338, the Community Assistance, Recovery and Empowerment Act (CARE) into law. The CARE Act incorporates a court system targeting people with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders, who may also have substance use disorders.

Newsom’s office is describing the program as a “paradigm shift” — but some advocates say that shift is in the wrong direction.

Already, unhoused people with severe mental health disorders can be involuntarily held in psychiatric care, but only for three days. They can leave only if they promise to take medications and make certain appointments. Using a court order, the CARE Act extends that period for up to a year, which can be extended to two years.

Family members, service providers and first responders — including paramedics or police officers — are among those legally able to file a petition with CARE court. If facing criminal charges, the individual could avoid punishment by enrolling in a mental health treatment plan. A judge could then order someone into treatment, including housing and medications.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon’s weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

“With overwhelming support from the Legislature and stakeholders across California, CARE Court will now become a reality in our state, offering hope and a new path forward for thousands of struggling Californians and empowering their loved ones to help,” Newsom said in a statement.

“This law violates a person’s right to self-determination and violates people’s right to choose how they want to and need to address their problems,” Sam Tsemberis told Salon.

It’s a first-of-its-kind law in the United States, but some other states have laws that share elements of the plan. The CARE Act was drafted by Senator Thomas Umberg (D-Santa Ana) and Senator Susan Talamantes Eggman (D-Stockton.) It goes into effect next year, but only in seven counties: Glenn, Orange, Riverside, San Diego, San Francisco, Stanislaus and Tuolumne.

Newsom’s office is describing the program as a “paradigm shift” — but some advocates say that shift is in the wrong direction.

“This law violates a person’s right to self-determination and violates people’s right to choose how they want to and need to address their problems,” Sam Tsemberis told Salon in an email. Tsemberis is the founder and CEO of Pathways Housing First Institute, a non-profit founded in 1992 that originated the Housing First model for addressing housing access. He characterized the law as politically motivated, citing Newsom’s alleged bid for U.S. president, and designed to appeal to voters “tired of seeing homelessness.”

“Based on my clinical experience and research comparing voluntary and involuntary court-mandated treatment programs, it is very clear that better outcomes are achieved when treatment is voluntary, trauma-informed, and compassionate,” Tsemberis said, adding, “This law will not have any impact on reducing homelessness because it does not provide funding for housing.”

Meanwhile, homes for people with severe mental illness are rapidly closing, with at least 96 facilities closing since 2016, according to the Los Angeles Times. In January 2020, the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness reported California has 161,000 people experiencing homelessness, including 7,600 students. The CARE Court program is estimated to help 12,000 people, Newsom’s office claims.

But the fact that police can intervene in these situations has alarmed some advocates. “Law enforcement and outreach workers would have a new tool to threaten unhoused people with referral to the court to pressure them to move from a given area,” Human Rights Watch said in April.

“Newsom’s ‘CARE’ Courts bill will not stop homelessness and it will not stop our mental health crisis,” James Burch, deputy director of the Anti Police-Terror Project, said in a statement, citing statistics that people with untreated mental health disabilities are 16 times more likely to be killed by law enforcement. The San Francisco Chronicle recently reported that nearly 1,000 people have been killed by California police in six years.

“The last thing that unhoused, the mentally ill and those struggling with addiction need is more surveillance that subjects them to being targeted by the police. The only real solution is permanent housing, access to adequate health care and community support,” Burch said.

Burch also said that the CARE Act would exacerbate systemic racism.

“Less than 7 percent of the state’s residents are Black, but Black people make up 40 percent of the state’s unhoused population,” Burch said. “It’s clear that ‘CARE’ courts will continue this country’s legacy of disproportionately policing and caging Black people. ‘CARE’ Courts will be a stain on Newsom’s legacy as future generations will ask how such an attack on human rights came to pass.”

Tsemberis suggested an alternative to the CARE Act, emphasizing his belief that housing is a basic human right and self-determination is the “best road to recovery.”

“The Pathways Housing First program is very effective in ending homelessness for people struggling with mental health and addiction issues,” Tsemberis said. “There are more than two dozen randomized-control studies reporting that participants in Housing First programs achieve 85 percent housing stability compared to 40 percent for programs that mandate sobriety and abstinence before offering housing.”

The CARE Act comes in the face of a bill Newsom vetoed last month that would have authorized supervised consumption sites, which are services that prevent overdose deaths by allowing drug use under medical supervision. New York opened two such sites recently, preventing more than 400 overdoses from becoming deadly so far. Such services are frequently used by unhoused people and have existed for decades in other countries without anyone ever dying at one.

“The same dysfunctional and non-scientific approach we take with homelessness is also evident in the way we address other public health problems,” Tsemberis said. “This CARE Court law is playing politics with the lives of people with serious addiction problems who will remain homeless.”