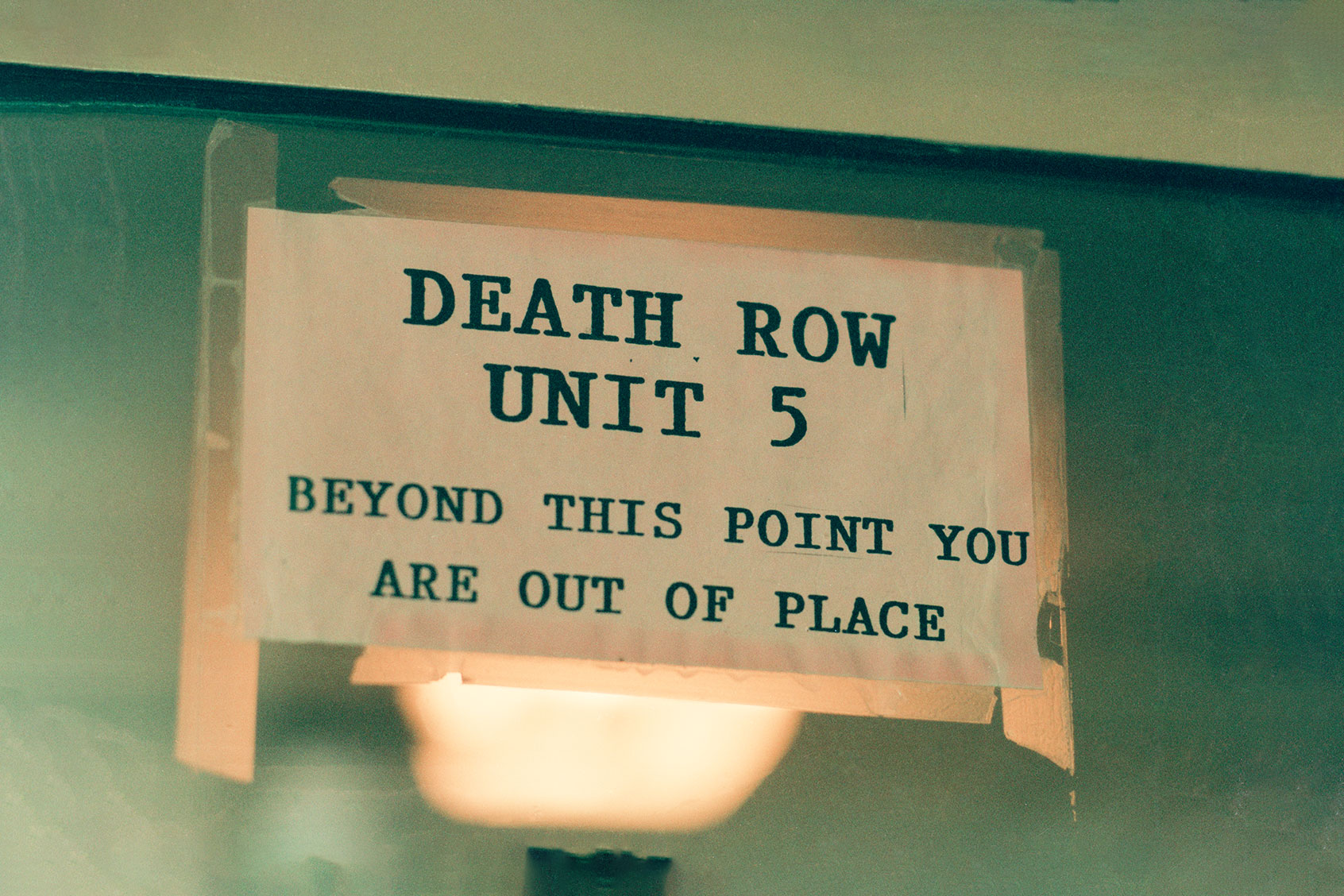

The state of Alabama wants to kill Alan Miller. But it is having a hard time getting its act together to do so.

On Sept. 12, Alabama made headlines when it announced that it would use nitrogen hypoxia to put Miller to death. It had added this method to its execution arsenal in 2018, making Alabama one of just three states (along with Mississippi and Oklahoma) to authorize it. But none of them has yet to use it in an execution.

Nitrogen hypoxia is a new and so far hypothetical method of administering capital punishment in which the air someone breathes is replaced with 100 percent nitrogen. As a CBC report explains, this will “deprive the person of the oxygen needed to maintain bodily functions,” presumably leading to a rapid and painless death.

Three days after that announcement, Alabama abruptly reversed course and said it would use lethal injection to execute Miller. If it goes through with this plan, Miller, who was convicted of a triple homicide in 1999, will be the 71st person the state has put to death in the last half-century. (Miller’s execution was originally scheduled for Sept. 22, but a federal judge has issued a preliminary injunction halting that process until the confusion surrounding Alabama’s handling of inmate requests regarding the method of execution can be cleared up.)

Given Alabama’s long experience with capital punishment, one might think that its executions would go off like clockwork. A look at the bureaucratic ineptitude and confusion in the run-up to Miller’s execution, however, strongly suggests otherwise.

The problems plaguing Alabama’s death penalty system and its plan to execute Miller are not just its own problems. They are frequent occurrences in other death penalty states as well. Those problems show how far short this country has fallen from fulfilling the spirit of “super due process” and scrupulousness which the Supreme Court once promised to all people who are accused or convicted of capital crimes.

The story of the snafus in the Miller case actually started four years ago, when Alabama changed its death penalty law to permit execution by nitrogen hypoxia. Like many other death penalty states, Alabama has had difficulty securing reliable supplies of lethal injection drugs.

Alabama’s new law gave death-row inmates 30 days to decide if they wanted to die by nitrogen hypoxia, but failed to specify exactly how they could exercise that choice.

The new law gave death row inmates 30 days to decide if they wanted the state to use nitrogen hypoxia as their execution method. But it failed to specify exactly how a death row inmate could exercise their choice, beyond noting that they could opt in by informing the prison warden “in writing.” If they did not do so, they would be executed by lethal injection.

Trouble began almost immediately because Alabama officials refused to take any clear steps to inform death row inmates about what they had to do if they wanted to choose nitrogen hypoxia.

They finally distributed information and a form for inmates to fill out which had been created by a group of federal defense attorneys, who have many clients on Alabama’s death row.

Miller says he remembers completing the form and returning it soon after he received it. He indicated that he preferred execution by nitrogen hypoxia rather than lethal injection. As he put it, “I did not want to be stabbed with a needle.”

Since its first use in 1982, lethal injection has proven to be America’s least reliable execution method. With its dismal track record, who could blame Miller for preferring to die in some other way?

Miller chose nitrogen gas because it reminded him of the nitrous oxide gas that is used in dentist offices. At least in theory, breathing pure nitrogen will lead to unconsciousness within a few seconds, followed by death.

But in a truly Kafkaesque situation, the state now says it never received Miller’s form. If that were an isolated case it would be bad enough, but as the Montgomery Advertiser notes, “Miller is not the first person on death row to say the state lost their election form.”

Fearing that the lost form would mean that the state would execute him by lethal injection, Miller sued in federal court, claiming, among other things, that lethal injection violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

Alabama’s mixed signals about execution methods began to unfold when James Houts, a deputy state attorney general — who had resisted Miller’s desire to die by nitrogen hypoxia for several years — unexpectedly informed U.S. District Judge R. Austin Huffaker Jr. that Alabama was “very likely” to use nitrogen hypoxia for Miller’s execution.

Preparations then proceeded to the point where the state wanted to fit Miller for the mask that would be used to administer the pure nitrogen.

Houts told the court that the “protocol” for using nitrogen hypoxia existed, “but I won’t say it’s final.” The last step was to make sure it was “nested” into the state’s existing execution protocol. Giving the final go-ahead, Houts said, would be up to the state’s corrections commissioner.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Last-minute changes to a state’s execution plans, like the kind that Alabama announced in the Miller case, often lead to mishaps. Unfortunately, they have been a part of this country’s death penalty system for a long time.

Last Thursday, Alabama changed course yet again when Department of Corrections Commissioner John Hamm told Judge Huffaker that his department could not “carry out an execution by nitrogen hypoxia” on Sept. 22.

While officials had “completed many of the preparations necessary for conducting executions by nitrogen hypoxia,” Hamm said, the full protocol needed was “not yet complete.”

So Miller again faces execution by lethal injection. Given Alabama’s own troubled history with that method, this is indeed a grim prospect.

It was only last July that Alabama took more than three hours to kill Joe Nathan James. During that time, the execution team made repeated attempts to insert the IV needed to carry the lethal chemicals before it was finally able to do so.

Last July, Alabama took more than three hours to kill Joe Nathan James. Four years earlier, it gave up on executing Doyle Hamm after two and a half hours, leaving him with puncture wounds in his groin, bladder and femoral artery.

The results of an independent autopsy indicated that James suffered greatly during what turned out to be the longest botched lethal injection ever.

Four years earlier, Alabama officials tried for two and a half hours to find a usable vein in Doyle Hamm. By the time they gave up and Hamm’s execution was halted, he was left with 12 puncture marks, including six in his groin and others in his bladder and his femoral artery.

These executions give the lie to the promise that lethal injection would, as Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once said, ensure an “enviable” and “quiet death.”

It is time to give up such illusions and to acknowledge the death penalty’s many failures.

Another late Supreme Court justice, William Brennan, once expressed the hope that Americans would “one day accept that when the state punishes with death, it denies the humanity and dignity of the [condemned] and transgresses the prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.” That day, Brennan said, “will be a great day for our country… [and] for our Constitution.”