The year was 1957, the game show was called "I've Got A Secret" and the guest had a most mysterious and ominous name: Dr. X.

Since the premise of "I've Got A Secret" was that contestants had to guess an unknown fact about the show's guests (Dr. X was joined that night by a popular comedian, Buster Keaton), the contestants immediately probed Dr. X for details. When one of them asked if he invented a machine that is painful when used, the soft-spoken Dr. X cracked up the audience by replying, "Yes, sometimes it's most painful."

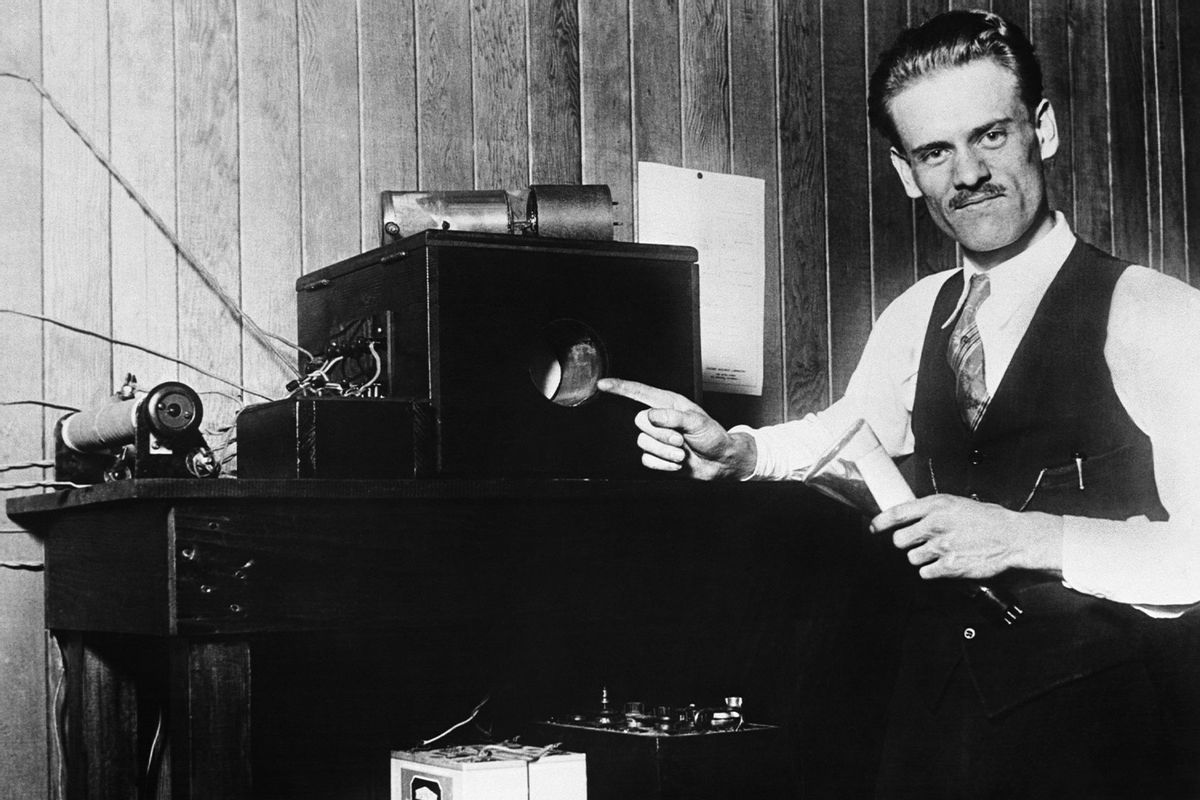

Dr. X, as it turned out, was Philo Farnsworth — inventor of the electronic television when he was only a teenager. While today television is widely lauded for providing us with great works of art (it even has a golden age and platinum age), in Farnsworth's time it was regarded by many with the same contempt reserved for new forms of entertainment media in every era. Farnsworth, however, had additional and personal reasons for feeling bitter toward television.

He had lived the American dream by coming up with a great invention all on his own, then suffered because he was woefully underprepared to face the hyper-competitive, often cruel business world that defines American capitalism.

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Like a character from a Horatio Alger story, Farnsworth was born in 1906 in a log cabin built by his grandfather in southwestern Utah. From an early age he showed a knack for science, voraciously reading magazines like Popular Science and Science and Invention, teaching himself physics and the works of Albert Einstein, and tinkering with machines whenever he found them (he even set up electricity in his rural farmhouse). In 1922, Farnsworth worked with his high school chemistry teacher Justin Tolman on a sketch for a so-called "image dissector" vacuum tube that essentially created the technology for modern television.

Before most people have even decided on a career path, Farnsworth had already figured out that the most effective way of transmitting images across large distances was to send them as a beam of electrons, which are then reproduced line by line along a light-sensitive screen. He did this at the age of 14, in fact, while plowing his family farm and visualizing beams of electrons patterned like the furrows he was created. With this epiphany, Farnsworth solved an intractable problem that had existed with previous attempts at television, which had used a more primitive and less reliable method.

Farnsworth had the right ideas, but lacked the economic good luck required to make the most of them in a capitalist society. Despite being admitted to Brigham Young University at the age of 16 (his grandfather had been a follower of the original Young), Farnsworth ultimately withdrew because his father's unexpected death meant he could no longer afford college tuition. Refusing to let his dream die with his formal education, however, Farnsworth rustled up funds for his invention even while supporting his family with a full-time public service job in Salt Lake City. By Sept. 7, 1927 (the same year as the release of the first sound motion picture, "The Jazz Singer"), Farnsworth and his team of engineers were successfully transmitting televised images of a line and a triangle to impressed investors. His last image, a dollar sign, was met with amusement — and, more importantly, additional funding.

When one of them asked if he invented a machine that is painful when used, the soft-spoken Dr. X cracked up the audience by replying, "Yes, sometimes it's most painful."

Funding that Farnsworth very much needed. While he had revolutionized television technology, he still struggled with picture clarity and other technical issues. He was not alone in developing new ideas for transmitting images; among others, an engineer named Vladimir Zworykin was working with the president of electronics firm Radio Corporation of America (RCA), David Sarnoff, to one day become the so-called "fathers of television." In 1930 Zworykin met Farnsworth in his San Francisco laboratory (Farnsworth believed it to be a good faith exploratory visit), observed and expressed admiration for his improved image dissector, and then returned to his own facility in Camden, New Jersey to make an even better camera tube known as an iconoscope.

This is where Sarnoff enters the picture — a man who was later described by one of RCA's successor companies as "the Bill Gates of his age" because he insisted on having "a stranglehold over an entire sector of the economy." Unable to run Farnsworth out of business through fair competition, Sarnoff paid a surprise visit to Farnsworth's business in 1931, and shortly thereafter offered to buy Farnsworth out. When Farnsworth refused, Sarnoff cooked up a bogus legal case, filing frivolous patent lawsuit after frivolous patent lawsuit against him in order to tie him up in court. Although Farnsworth ultimately prevailed, the ordeal broke him both physically and mentally. Soon he developed severe depression and alcoholism. Even though Farnsworth's legal victory in 1939 technically meant that RCA would have to start paying him to manufacture televisions, World War II temporarily stifled the television market. By the time the general public actually took an interest in television, Farnsworth's patents had expired. Soon thereafter, he went out of business.

If there is any consolation to this story, it is that Farnsworth did continue inventing in his later years. While he stumped the contents on "I've Got A Secret" (winning a carton of cigarettes and $80, or roughly $843.19 by modern standards), Farnsworth's name would soon overtake Zworykin and Sarnoff in the popular consciousness as the primary inventor of television. Before his death from pneumonia in 1971, Farnsworth even somewhat revised his earlier dismal opinion of television, which his children recalled him outright lambasting while they were growing up. His widow, Elma Farnsworth, later told historians that when he saw Neil Armstrong land on the moon on July 20, 1969, he finally believed that his own contribution to sharing that event with the world made his travails somewhat worthwhile.

Shares