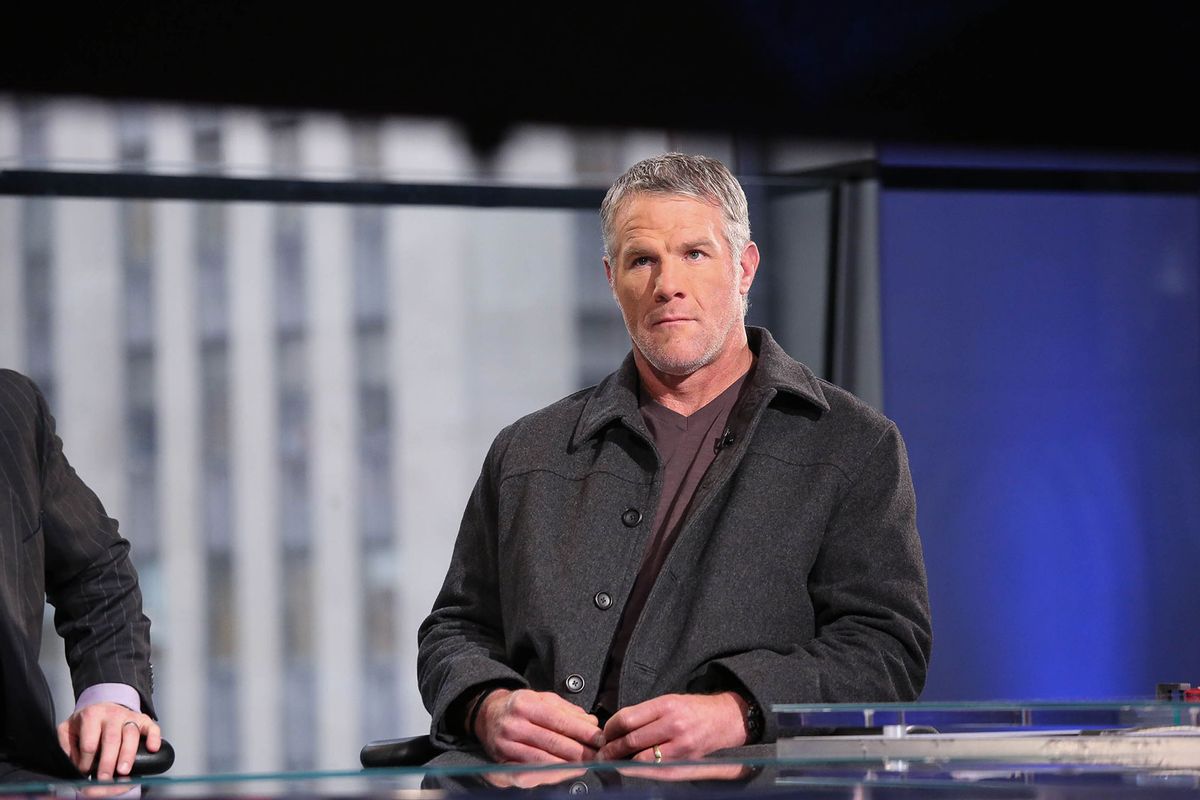

Ignoring the poor is a great American pastime for the one percent. According to recent news reports, former NFL quarterback Brett Favre may have found a way, via his alleged involvement in a massive corruption scandal in Mississippi, to stand out in that game, too.

The Hall of Famer has been embroiled in a complex web of allegations involving welfare funds meant for families experiencing poverty being diverted to fund, among other questionable projects, volleyball and football facilities at the University of Southern Mississippi, Favre's alma mater, where his daughter also played volleyball at the time.

Investigations alleging Favre's entanglement in Mississippi welfare fund misuse date back several years, with ESPN reporting in 2020 that a "nonprofit group caught up in an embezzlement scheme in Mississippi used federal welfare money to pay former NFL quarterback Brett Favre $1.1 million for multiple speaking engagements, but Favre did not show up for the events." The nonprofit had contracts through the state's Department of Human Services funded by Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and allegations of misuse led to criminal charges being filed against nonprofit leaders and state officials in 2020.

Favre has denied those allegations, claiming in 2021 on Twitter that he "would never accept money for no-show appearances," that he was paid for commercials, but "[o]f course the money was returned because I would never knowingly take funds meant to help our neighbors in need."

In May of this year, Mississippi DHS sued Favre and several others in an attempt to recover some of the lost funds, which the Associated Press reports total "millions in misspent welfare dollars that were intended to help some of the poorest people in the United States."

And now, text messages have surfaced in court filings that appear to show former Gov. Phil Bryant helping Favre find funding for a new volleyball stadium using welfare funds, reported Mississippi Today in an explosive five-month investigation that brought the state's scandal back into national headlines. "Bryant has for years denied any close involvement in the steering of welfare funds to the volleyball stadium, though plans for the project even included naming the building after him."

In July 2019, ESPN reports, "Bryant texted Favre that the founder of a nonprofit who paid him 'has some limited control over Federal Funds in the form of Grants for Children and adults in the Low Income Community.'"

"Use of these funds [is] tightly controlled," Bryant wrote, according to the filing. "Any improper use could result in violation of Federal Law. Auditors are currently reviewing the use of these funds."

The following month, the filings show Favre texting the nonprofit leader, "If you were to pay me, is there any way the media can find out where it came from and how much?"

None of this looks good for Favre's reputation.

Favre texted Bryant again in September 2019, according to the filing: "We obviously need your help big time and time is working against us," Favre wrote. "And we feel that your name is the perfect choice for this facility, and we are not taking No for an answer! You are a Southern Miss Alumni, and folks need to know you are also a supporter of the University."

Bryant responded, "We are going to get there. This was a great meeting. But we have to follow the law. I am to[o] old for Federal Prison."

None of this looks good for Favre's reputation. He returned the $1.1 million, but the state is still seeking $228,000 in interest. He has not been charged with any crimes. But Sirius XM has placed his talk show on hold, and NBC Sports reports that his weekly appearances on ESPN Milwaukee have been suspended until further notice. Is that enough? So far, a rich man has forked over a relatively small slice of unearned dough from his otherwise massive sports-built empire.

Maybe Favre, who ranks among the NFL's highest-paid players of all time and was fortunate enough to grow up in a two-parent household headed by college-educated parents who both worked as teachers, suffers from affluenza now. Maybe he can't fully understand that there are poor people in Mississippi who need assistance for matters more pressing and important than new athletic facilities for his daughter's volleyball team.

We fought through public housing and blocks of cheese and government-issued peanut butter until semi-gainful employment was available.

If I had Brett's ear, I'd tell him about Coach Kevin in northeast Baltimore whose football team — kids ages 9-11, who love the game just like he does — practices in the dark, often running into each other, because the district lacks lights. That is what poverty looks like. Or I would tell Brett my own story, about the times we had to use the oven to heat our home during the winter and eat cereal with a fork to preserve the milk because we were broke and fighting our way through rough stretches. We weren't lazy and we didn't lack ambition, we just didn't get callbacks for jobs because companies didn't hire dudes with names like Dante or Keon. We fought through public housing and blocks of cheese and government-issued peanut butter until semi-gainful employment was available. And even when we beat public assistance, poverty blanketed our experience. Government funds are a small piece of it. The bigger battle involves securing stable housing, navigating adequate nutrition while living in food deserts, studying in underfunded schools and dealing with the way police officers treated us. We all needed more from a system that failed us repeatedly.

A system that has failed people for generations isn't Brett Favre's fault. I don't think people should call for his arrest. However, this would be a great opportunity for the quarterback to listen to people who may not have been as fortunate. He should spend some time around Mississippians who were hurt by a lack of available funds for public assistance. He could use his platform to amplify those ongoing issues. Maybe some of those poor kids would get a boost up, and end up attending a school like Southern Miss themselves. Maybe as alums, they'd become successful enough to help build new university facilities themselves — the honest way.

Shares