How did Ser Criston Cole get away with it?

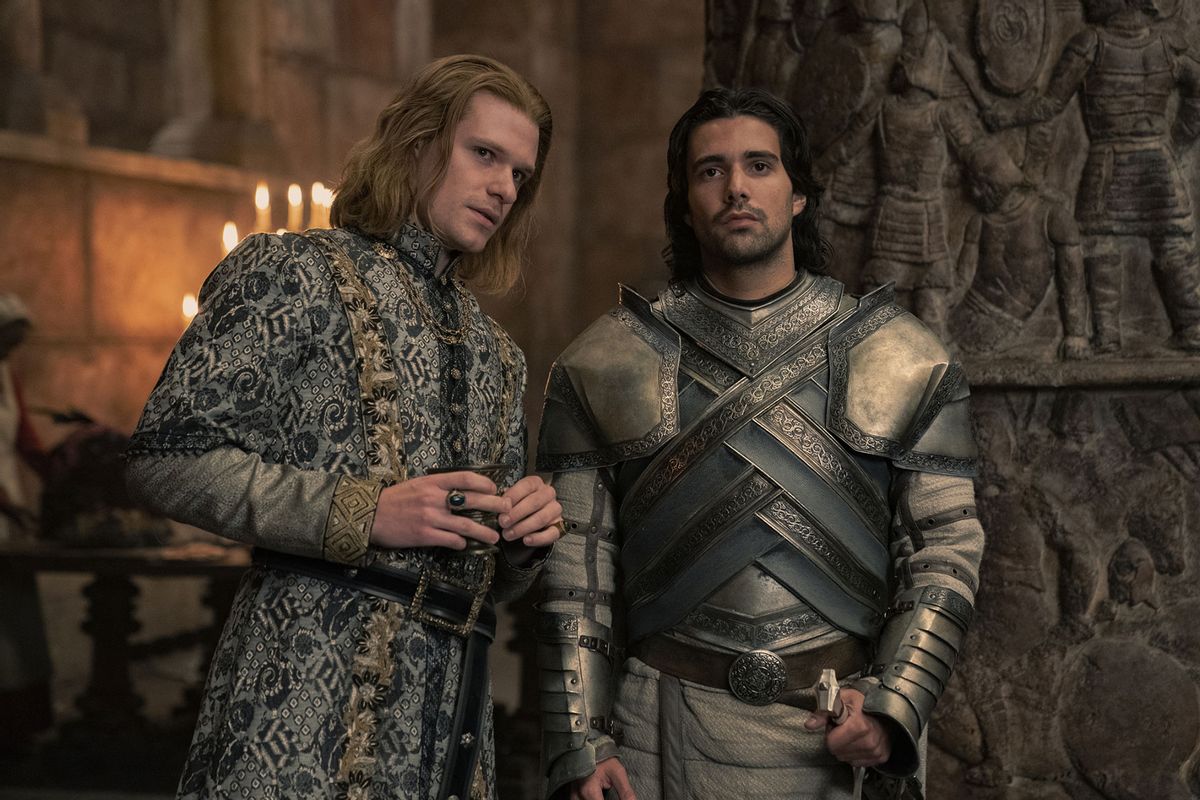

It's a question burning up much online discourse about the two most recent episodes of "House of the Dragon," the "Game of Thrones" prequel series that focuses on the dragon-riding royal family of House Targaryen. Cole (Fabien Frankel) first presents in the series as a dashing hero, a humble knight of a lower house who has risen to serve on the Kingsguard, primarily protecting Princess Rhaenyra (Milly Alcock and Emma D'Arcy). By the fifth episode, "We Light the Way," however, Cole has revealed himself as a villain, interrupting Rhaenyra's wedding feast by beating to death Ser Joffrey Lonmouth (Solly McLeod), the charming but secret lover of the groom.

George R.R. Martin uses this structure to explore one of the stickiest problems of cataloging history: How do we know what we think we know?

Juicy soap opera drama stuff, of course, all against a backdrop of medieval tapestries and CGI dragons. But what has got people talking — many with no small amount of frustration — is everything we don't see before and after this violent crime. We know the proximate reason Cole was angry at Lonmouth, who had previously been teasing Cole for his own secret affair with the bride. But we never see the interaction that tipped Cole over the edge to murder. Like the wedding guests, all we know is one minute everyone is dancing and feasting, and the next minute, one man is beating another man's head into a pulp.

To deepen the mystery, the next episode jumps forward 10 years and there Cole is, seemingly unpunished for a cold-blooded murder, one that ruined the royal wedding. All we know is he's allied with the powerful Queen Alicent Hightower (Emily Carey and Olivia Cooke), but the particulars are left unspoken. Did she protect him? What story did they tell? Why didn't Rhaenyra or her husband, Ser Laenor Velaryon (Theo Nate and John Macmillan), do more to have Cole punished?

Quite a few fans of "House of the Dragon" are driving themselves a bit mad wondering why we don't have answers to these questions. But this deliberate ambiguity draws heavily from the book the series is based on, "Fire & Blood" by George R.R. Martin. "Fire & Blood" isn't just a fantasy novel about the adventures of some rich, violent dragon-riders. The premise of the book is that it's a historical tome written by a fictional Archmaester Gyldayn. Martin uses this structure to explore one of the stickiest problems of cataloging history: How do we know what we think we know?

Throughout "Fire & Blood," Gyldayn draws on many conflicting sources and rumors, and repeatedly confesses to the reader that the full truth of events is lost to time. We often don't know who murdered who — or why. We don't know who slept with who. (The show is on HBO, however, so that question is often answered in great detail.) As a bit of postmodernism injected into a fantasy novel, it's thought-provoking. But it's also just plain fun for readers, because it invites speculation and debate.

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

Before "House of the Dragon" aired, the assumption was that this aspect of the novel would be dropped. The camera is a blunt instrument. We believe what is onscreen, unlike what is whispered in corridors, is the plain truth. But the show constantly toys with that assumption, often simply by putting the camera somewhere else when the action is happening, especially when it comes to the mysterious Prince Daemon Targaryen (Matt Smith). Did he really call his dead infant nephew "heir for the day?" Did he really have sex with his niece? Did he intend to kill his first wife? Did he steal that dragon egg? We know what characters on the show believe, but we often don't know the truth, because the camera either cuts away or uses ambiguous angles.

Matt Smith in "House of the Dragon" (Ollie Upton / HBO)The frustrating inaccessibility of historical fact is a theme sewn throughout the show. It's underscored in a conversation between King Viserys Targaryen (Paddy Considine) and his wife in the sixth episode, "The Princess and the Queen," as they argue over Alicent's belief that Rhaenyra's children look more like her presumed lover than her gay husband. Defending his daughter, Viserys recounts the story of a black mare who mated with a silver stallion, producing an unexpectedly chestnut foal.

Matt Smith in "House of the Dragon" (Ollie Upton / HBO)The frustrating inaccessibility of historical fact is a theme sewn throughout the show. It's underscored in a conversation between King Viserys Targaryen (Paddy Considine) and his wife in the sixth episode, "The Princess and the Queen," as they argue over Alicent's belief that Rhaenyra's children look more like her presumed lover than her gay husband. Defending his daughter, Viserys recounts the story of a black mare who mated with a silver stallion, producing an unexpectedly chestnut foal.

"How do you know? The silver stallion. How do you know it was him?" Alicent replies. "Did you witness the act itself?"

"How do you know?" is a question that plagues us in the 21st century, as the processes of establishing facts are increasingly under assault by malicious actors: Donald Trump and his Big Lie, COVID-19 denialists, apologists for police murders. And nowhere is this fight uglier than when it comes to how we know historical fact. Right wing activists across the country are purging schools of historical facts under the guise of fighting "critical race theory," and propping up narratives to flatter their own sensibilities. When confronted about falsehoods and conspiracy theories, conservatives often respond like Alicent: How do you know? Were you there? Are you a scientist? Aren't "alternative facts" as good as real ones?

(Yes, Alicent happens to be right in this instance on the show, but the beauty of fiction is it can often have the nuance dumb real life politics don't have.)

The uncomfortable truth is that we often don't know. We're living through a pandemic, where the expert advice morphed from "don't touch anything" to "nope, it's airborne, so wear a mask." Ignorance still plagues the human race. A lot of what we "know" is wishful thinking, as anyone who talks to a Fox News addict can tell you. But even those who have more rigorous standards and good intentions still often "know" things not because we saw it ourselves, but because we inferred it or we listened to those we believe to be experts.

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

None of this is to say that truth is totally subjective and all "facts" are equal. Critical thinking really comes down to learning to infer with accuracy and selecting your expert opinions wisely. Close readers of "Fire & Blood" end up having a strong picture of the "true" story Martin is telling behind the muddled telling. It's a book that rewards a reader for being a sharp thinker, and for applying what they know about the world of Westeros and about human psychology to the conflicting accounts. They may not be right all of the time, but if they're good at this, they'll be right most of the time.

With that in mind, we return to the question: How did Ser Criston Cole get away with murder? No, we don't know — and may never find out — the lie he told about his motives. But what we do know is that he is one of the most elite knights in Westeros and he's aligned with a powerful, conservative queen. We also know it's an open secret in their world that his victim was gay. We can draw on our real-life knowledge that, when police kill marginalized people, they often get away with it. From that, we can infer what happened. I personally don't even want to know what lame story he concocted to excuse murder. All that matters, in the end, is power. That's the kind of deeper truth that good fiction can convey, even as it obscures the more banal question of facts.

"House of the Dragon" airs Sundays at 9 p.m. on HBO.

Shares