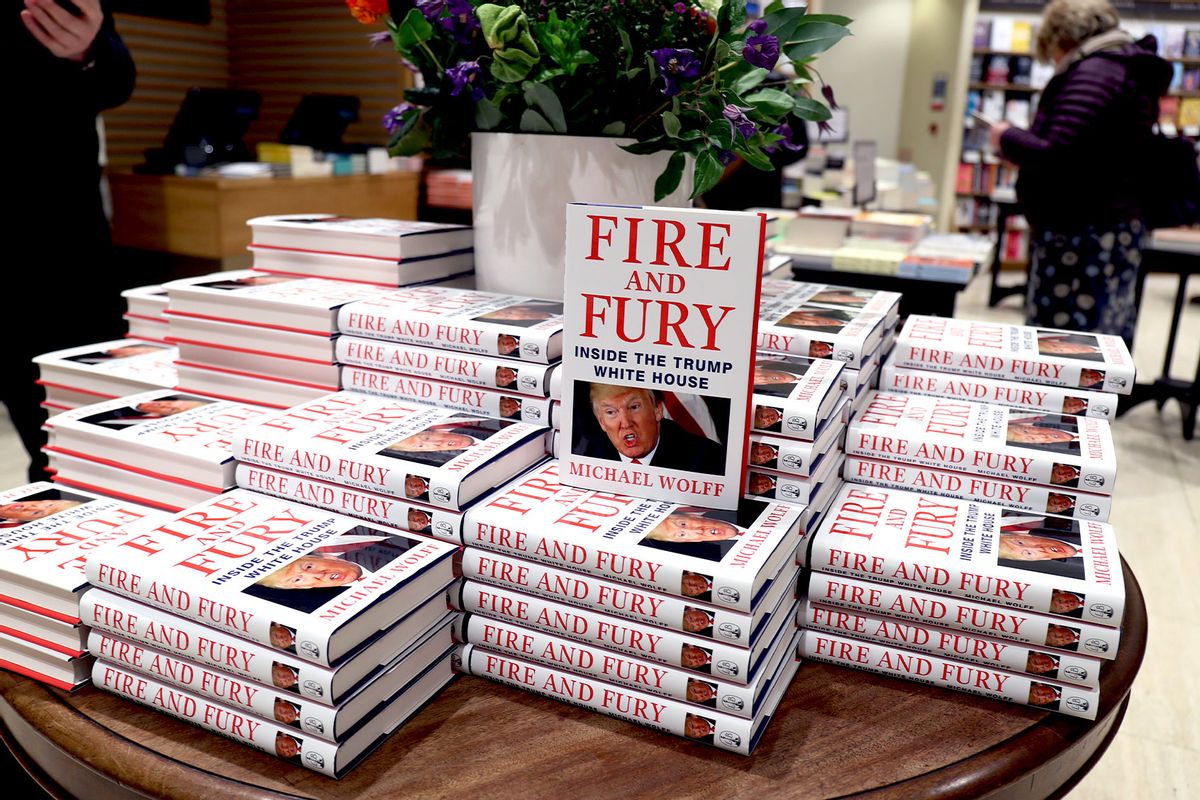

The Economist posted a list this month entitled "What to read to understand Donald Trump," a list of five "handy books" from the overflowing library of volumes about the man who, as the editors put it, "remains at the center of American politics." These include the first major book about the Trump White House, Michael Wolff's 2018 "Fire and Fury," and several other classics of this mini-genre: "Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America" by John Sides, Michel Tesler and Lynn Vavreck; John Bolton's White House memoir, "The Room Where It Happened" and two accounts of the end of Trump's presidency, "Frankly, We Did Win This Election," by Michael C. Bender, and most recently "Thank You for Your Servitude: Donald Trump's Washington and the Price of Submission" by Mark Leibovich.

Taken together, those five books about Trump World capture a great deal of the the political intrigue, scandalous gossip and incoherent policy-making of Trump's two presidential campaigns and his chaotic administration. But I would argue they explain far more about the boss' enablers and his MAGA supporters than they do about Trump himself, his 75 years of life or personal history.

If you want to understand Donald Trump's personality and his interrelated behavior in business, politics, and crime, I would recommend this alternative list: five other books that provide meaningful and serious examinations of Trump's social-psychological makeup and his family, emotional and social development:

- "The Making of Donald Trump" (2016) by David Cay Johnston

- "Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World's Most Dangerous Man" (2020) by Mary R. Trump

- "The Strange Case of Donald J. Trump: A Psychological Reckoning" (2020) by Dan P. McAdams

- "Disloyal, a Memoir: The True Story of the Former Attorney to the President of the United States" (2020) by Michael Cohen

- "Tower of Lies: What My 18 Years of Working with Donald Trump Reveals About Him" (2020) by Barbara A. Res

From the perspective of criminology, which is my field, what is particularly interesting about these 10 Trump books is that with the exception of those by Bolton, Johnston and Cohen, there are no substantive discussions of Trump's evident corruption, or more than cursory examinations of his criminal career in business, politics and government.

Without an appreciation or a less-than-superficial understanding of the nature of the crimes of the powerful, their habitual patterns of lawlessness and the normalization of these crimes — not to mention the systemic resistance to holding powerful perpetrators accountable — there is palpable jeopardy that people will not understand that, like other criminals, they are created in relation to their personal social status and their social identification experiences. And furthermore, that the types of crimes committed by the most powerful offenders also result from their personal biographies, and particularly their experiences with crime control and law enforcement (if any).

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Without this level of understanding of the etiological voyage of Donald Trump's criminality and impunity, especially in relation to how he became for four years the most powerful person on earth, most people view him through a lens of cognitive dissonance. They are likely to think of Trump as mentally ill or deeply irrational — an innately evil individual or some kind of "born criminal." In that view, whatever else Trump may be, he cannot possibly be a "rational" actor.

I would forcefully argue that's not true. More important, this discourse focused on Trump's perceived insanity, ignorance or immorality works to mitigate, both socially and legally, against more accurate perceptions of his rationality, intentionality and level of culpability.

Consider Lloyd Green's book review for the Guardian of Michael Wolff's third Trump book, "Landslide: The Final Days of the Trump Presidency." This is Wolff's best and "most alarming" book, Green writes, and "that is saying plenty," especially since "Fire and Fury" had both "infuriated a president" and "fueled a publishing boom."

Most people view Trump through a lens of cognitive dissonance: His behavior doesn't make sense, so he's mentally ill or deeply irrational or innately evil. None of that is true.

Wolff's new book describes Trump's "wrath-filled final days in power" exemplified by an interview that Wolff held in the lobby of Mar-a-Lago. Wolff simply allows Trump to rant through a classic "exercise in Trumpian score-settling," without even trying to push back against the cascade of lies. As Wolff admits, he was reluctant to interrupt or ask serious questions because he knew that the interview would have come to an abrupt end had he done so. So Trump simply babbles on nonsensically, to no obvious purpose for either man.

As I have written elsewhere about Wolff's conclusions, he "argues non-persuasively that the Donald was too crazy" to be genuinely guilty of plotting a coup or other criminal behavior. Wolff sees Trump as experiencing "swings of irrationality and mania," and as "someone who has completely departed reality. Trump was incapable of forming specific intent, he argues, based "on the calculated and 'coordinated' misuse of power."

Wolff is not alone. Indeed, the slew of books documenting Trump's final days in office tend to agree on this analysis, along with most cable TV talking heads, with the obvious exception of those on Fox News. The consensus, more or less, is that Trump's loss to "Sleepy" Joe Biden broke him, and that his fantasies, as captured in the title of "Frankly, We Did Win this Election," are evidence that he was seriously deluded, and not just acting deluded.

Here's a similar take from Daily Kos on Trump books and election delusions:

Losing the election untethered him from whatever scraps of reality his advisers had still managed to tie him to, and up he went like a lost balloon with anger management issues. By the end he was (is) wallowing in delusion, ordering staff to do impossible and/or illegal things, absolutely convinced that everything was a conspiracy and that anyone who didn't tell him what he wanted to hear was in on it.

Let me disagree firmly, and speak from the clinical evidence. Trump has never been tethered to reality — but that does not necessarily mean he believes his own delusions. Similarly, while some of his presidential advisers may have resisted to varying degrees or pushed back against his more unhinged desires, they never had him tied up or taken away in a straitjacket. Some of his own appointed Cabinet members saw his behavior as crazy or unstable from the beginning, and reportedly talked about invoking the 25th Amendment at various times — but never did so.

For many years, perhaps for his whole life, Trump has been bipolar, irrational, paranoid, narcissistic and sociopathic. Those qualities do not necessarily mean that he is delusional or legally insane, or that he lacks criminal intent. Trump knows as well as anybody does, and probably better than most, the differences between "fake news" and legitimate information.

But here's what's most important: Trump knows he is guilty of all the crimes he has been accused of. He also knows he has no genuine defenses for any of those likely or potential charges, which is why he so persistently seeks to lie, to obfuscate and to delay. He also understands that his best defense, at least in the court of public opinion, is a forceful offense: Always a master of projection, he charges his legal accusers with sinister and conspiratorial motivations.

Trump feels no empathy whatsoever for any of the Jan. 6 rioters and could not care less about their legal travails, adjudications or punishments. Whether we're talking about insurrectionists or FBI agents, Trump simply uses them instrumentally, as he uses everybody else, to satisfy his bottomless narcissism and egotistical needs. It's the modus operandi of a sociopath without the psychological ability to identify with either of those two groups, or literally any other, including the "base voters" of the Trump cult.

Trump is deceitful, but not deluded or delusional. He's a con man, performance artist and demagogue — who understands the value of never publicly abandoning his most absurd narratives.

To state this differently, Trump is deceitful, but not deluded or delusional. Unlike Ginni Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Trump does not really believe that he won the 2020 election or that it was rigged against him. While he may post on his social media platform that he "loves" the Jan. 6 rioters, he does not really believe they are "nice" people. Nor does he believe for one second that "evil" FBI agents planted classified documents at his office in Mar-a-Lago, or that GOP Senate leader Mitch McConnell a "DEATH WISH," political or otherwise.

He is a con man, performance artist and demagogue who understands the value of never publicly abandoning his narratives, no matter how absurd or blatantly false they are. He was able to suck in Michael Wolff, along with a whole lot of other people, to believe he was so deranged as to be incapable of forming the intent to stage a coup, let alone organizing one.

Really? This was the man who conducted cursory presidential business every day while watching the tube, eating fast food and tweeting 24/7, except when he was playing at least 27 holes of golf a week, or was out on the campaign trail delivering "greatest hits" monologues of unadulterated nonsense to the loyal followers he viewed with obvious contempt.

In the immortal words attributed to P.T. Barnum (among others), "There's a sucker born every minute." And the former president who was impeached twice and got away scot-free knows how to spot them.

Read more

on the current predicament of Donald Trump

Shares