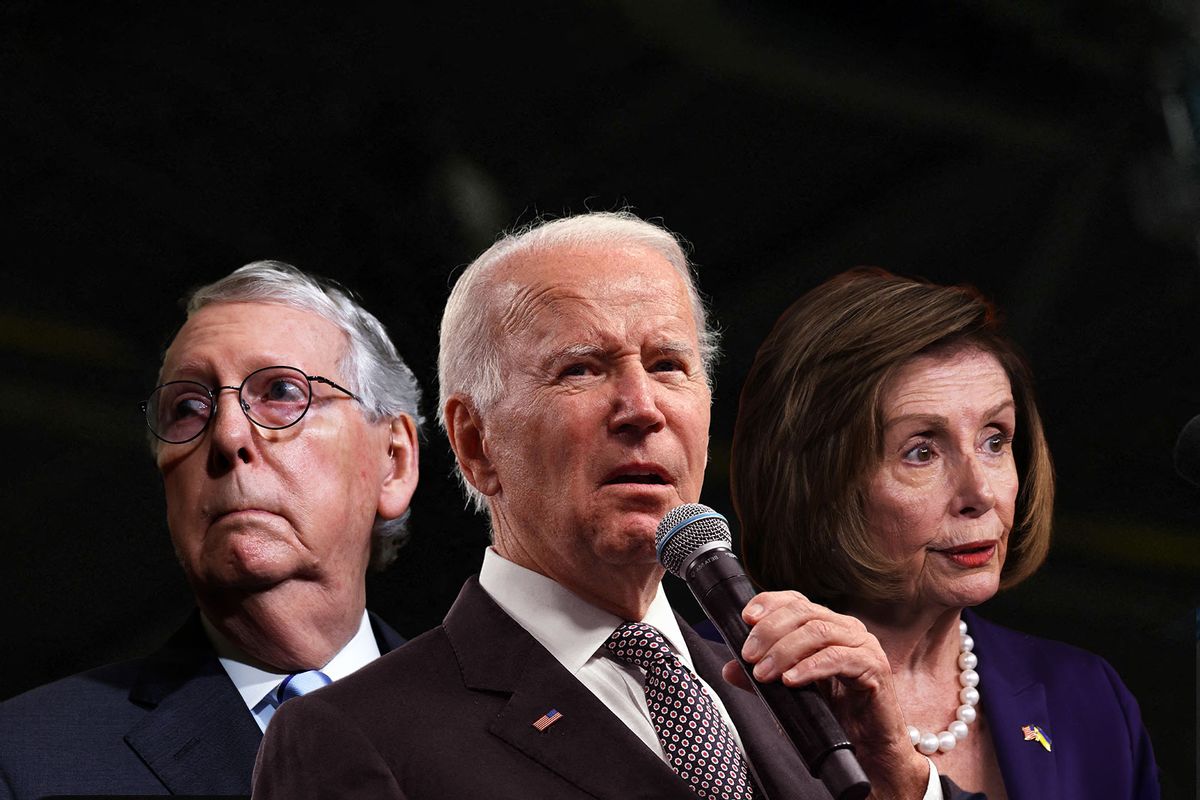

In the United States and around the world, the dangers posed to democracy have become both more numerous and more dire, but also easier to spot. Voter suppression, disinformation campaigns and outright coups are neither subtle nor morally ambiguous tactics, and their practitioners — almost always from the far right — have grown brazen, taking less and less care to hide their true motives. But even at this moment of overwhelming peril for our democratic institutions, whose significance is recognized by an increasing number of Americans, one anti-democratic policy has gained support from a startling number of people across the political spectrum: barring older citizens from holding public office.

Two polls released in September found that nearly 75% of respondents (including 71% of Democrats in one survey) favored establishing a maximum age for elected officials, a substantial increase from a YouGov poll conducted at the beginning of the year that found 58% support. While the motivations for favoring an age cap vary, most supporters are not tyrants in waiting. Instead they have bought into a simplistic solution to the broader and deeper problem of inequality that faces our democracy. Such a ban is virtually impossible to implement, since it would require a constitutional amendment. It would accomplish very little, compared to how severely it would disenfranchise tens of millions of older Americans. In fact, the entire idea of an age cap presents a dilemma: How can we thwart the most virulent attacks on democracy if we don't really believe in it ourselves?

Just as the best propaganda contains a kernel of truth, the most harmful policies purport to address a real problem. Numbers suggest that the 117th Congress is the oldest in history. The median age of senators is about 65 and House members about 59, while the median age of registered voters is about 50 and the overall median age of U.S. residents is just under 40. It's true that the American population is aging, but while that may account for the trend of aging leadership in absolute terms, it doesn't explain the widening gap between elected representatives and their constituents. In other words, the problem is real, but the emphasis placed on it and the extremity of the solutions on offer are distorted.

Some proponents of an age cap claim to be concerned about representation, and present themselves as advocates of a more robust democracy. Members of Congress are out of touch, they claim, because they came of age in a different era and cannot wrap their minds around the pressing issues of the day and the interests of a new generation. Representation, however, is multifaceted, as are the failures of our political system. Women, for example, remain underrepresented by about 50% in Congress. There are only three Black U.S. senators — and there have only been 11 in our entire history — although about 14% of the population is Black. The median net worth of House members in 2018 was nearly five times that of the median American household, while the median net worth of senators was nearly 17 times greater.

Members of Congress are definitely older than the median registered voter. They're also disproportionately white, male, wealthy, heterosexual, abled, Christian and college-educated.

While the fact that House members and senators are about 18% and 30% older than the median registered voter, respectively, is arguably significant, the fact that our leaders are also disproportionately male, white and wealthy (as well as heterosexual, abled, Christian and college-educated) almost certainly plays a larger role than age, and probably skews how we understand the age issue in the first place. Younger voters need greater direct representation, but throwing out older leaders simply for being older will do nothing to address the problem of unresponsive government, and will only distract us from the solutions that could.

Even taken on its own terms, an age cap is unlikely to increase youth representation in any meaningful way. Proponents do not agree on precisely where to place the cap, but in multiple polls a plurality of respondents chose age 70 as the cutoff. About one-third of U.S. senators and one-fifth of House members are 70 or older, so barring them would initially have a significant impact. A far larger number of members, however, fall between 50 and 69; that range accounts for more than half of the House and Senate. Some of those members would obviously hit the limit sooner than others, but the average age of new members — about 50 in the House and 55 in the Senate — paired with an average tenure of about nine years in the House and 10 in the Senate (both calculated from the past four Congresses), means that our leadership would immediately start getting older again. Within a short time, a new equilibrium would be established, somewhat younger but more tightly clustered than the previous one. Rather than causing Congress to become more representative, an age cap would likely lead to further homogenization: Young people would gain little or nothing, senior citizens would be excluded entirely and the already-dominant group of middle-aged politicians would become even more so.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Another argument that cap-proponents make is that older people are a liability in government because they may develop dementia. It's true that the risk of dementia increases with age, but of course old age doesn't guarantee that one's mind will falter, nor does youth guarantee that it won't. A small but growing number of people will develop younger-onset dementia in their 30s or 40s. If the goal is to reduce the risk of dementia, but not to increase youth representation, then an age cap could be moderately successful but only by resorting to scorched-earth tactics. Barring everyone older than 70 because a small fraction of them will develop some degree of dementia is collective punishment for a disorder that no one can control, and to which everyone is potentially susceptible. It's a clumsy and cruel solution to a comparatively small and unpredictable problem — it would not eliminate the risk of dementia among political leaders, but would certainly eliminate many qualified leaders who will never develop dementia, and would further erode the idea that older people can contribute meaningfully to our increasingly complex society.

The best thing we can say about an age cap as public policy is that it might succeed modestly, where another policy could have accomplished much more while causing less damage. As a political project, however, it's entirely futile. Imagining two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of state legislatures agreeing to amend the Constitution for any reason at all is challenging; imagining that for a proposal that would directly threaten congressional power is inconceivable. Furthermore, this is just a terrible idea. A one-size-fits-all ban would serve only to lump older people into an undifferentiated mass, and to further obscure the fact that every generation of human beings is politically, economically and culturally diverse.

Disenfranchising older people is a first step down the dangerous path of dehumanization, which as history teaches, can lead to the disposal of those deemed undesirable.

Implicit bias against the elderly is among the strongest against any social group. Baby boomers have been labeled a "generation of sociopaths," and the COVID-19 pandemic has been called a "boomer remover." Like other forms of social stigma, ageism can be internalized, potentially increasing the likelihood of early death and cognitive decline, and leading some to buy into the worst stereotypes leveled against them. That may help explain, for instance, why even many older people support an age cap. The disenfranchisement such a measure would establish is also a first step down the dangerous and well-trodden path of dehumanization, which as history teaches can lead to the disposal of those deemed undesirable. It also represents a reckless subversion of democracy, at a time when its foundations are already buckling.

The great aspiration of democratic politics is collective self-governance: Everyone works together to guide society toward the common good. This is an ideal worth fighting for, but it has not yet come to pass. As we strive for something better, democratic participation can be understood as a means of self-defense: Getting a seat at the table is how you become visible, fight for what you need and combat those who threaten to take these things away. We need more young people in government not simply because government is failing to serve them, but because they have the right to participate.

Enfranchisement is not just the right to vote, as it seems to be commonly understood. It's also the right to serve. And the right to serve, to have a place at the table, is not simply a means to an end but also a matter of dignity. Barring older people from holding office would risk leaving them defenseless within our degenerating political system. In the best of times, this would be abhorrent and risky — a perversion of democracy at its most basic level — but these are not the best of times. Asking whose fundamental rights can be revoked, and which swaths of the electorate can be excluded from full participation in the democratic process, should be unthinkable: It amounts to an inadvertent surrender to fascism.

Read more

about the struggle to save democracy

Shares