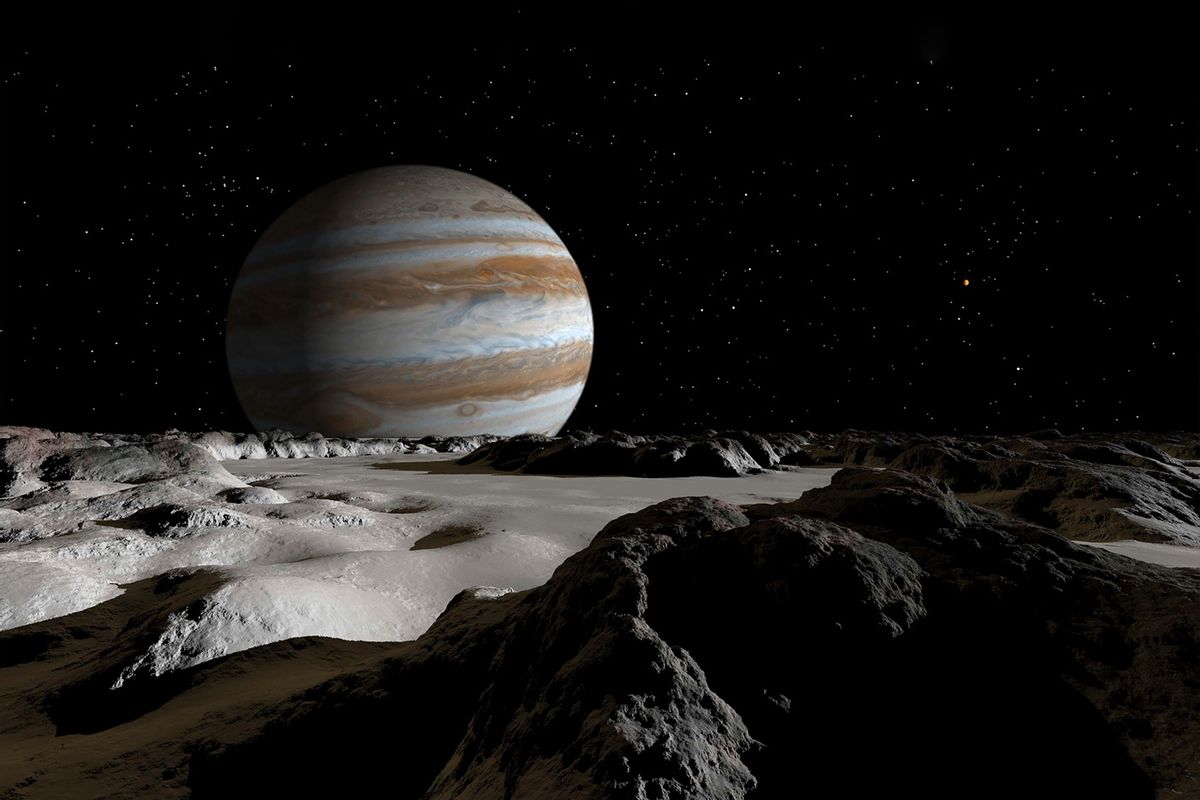

At first glance, Europa — the Jovian moon widely believed by scientists to be a prime candidate for harboring extraterrestrial life — appears unremarkable. It is mostly off-white and covered in tiny cuts known as "lineae" that appear as scratches on the surface, giving Europa the look of a scuffed-up pool cue ball. Yet despite its waiting-room-ecru shade, Europa is so intrinsically interesting that NASA has fixated on the moon as an object of study — which is why the agency is planning for the upcoming Europa Clipper mission (scheduled for 2023), where they hope among other things to learn about the water that covers the celestial body.

Part of the moon's appeal is that many of its secrets are hidden below its icy crust. Because Europa is constantly stretched by tidal forces from the gravity of the largest planet in the solar system, its interior is believed to have liquid oceans, though it lies beneath at least 10 to 15 miles of surface ice, planetary scientists say.

This is significant because, just as life on Earth originated from the vast array of water-based structures on our planet, life on Europa may very well be flourishing within any system of lakes that exists on that planet.

Now, NASA scientists are particularly excited about recent analysis of data from the Galileo orbiter. Though the Jupiter-orbiting probe's mission ended in 2003, the probe's data continues to be analyzed. As the space probe passed over Europa, it observed that there may be large reservoirs of salty liquid all over Jupiter's fourth-largest moon. Some could be close to the surface, but others are pockets of brine located miles deep.

In other words, Europa might not just have oceans. It may also have lakes.

The notion of lakes on Europa is significant because, just as life on Earth originated from the vast array of water-based structures on our planet, life on Europa may very well be flourishing within any system of lakes that exists on that planet.

Yet it would be a mistake to think of Europa as nothing but a water world. Galileo's images of Europa have also helped scientists learn that its icy crust is not just water, but filled with various unidentifiable minerals and salts. Although Galileo attempted to ascertain their composition using reflectance spectroscopy, it was unsuccessful.

"We mapped the distributions of the different materials on the surface, including sulfuric acid frost, which is mainly found on the side of Europa that is most heavily bombarded by the gasses surrounding Jupiter," team leader and University of Leicester School of Physics and Astronomy Ph.D. student Oliver King told Space.com in a statement. "The modeling found that there could be a variety of different salts present on the surface but suggested that infrared spectroscopy alone is generally unable to identify which specific types of salt are present."

Want more health and science stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

Europa's main allure, of course, is the tumultuous ocean that churns beneath its frigid white surface. First noticed by NASA's Voyager probe in the 1970s, astronomers were fascinating that Europa could maintain a liquid water ocean despite being so far away from the Sun. Some scientists believe that tidal forces on Europa generate enough heat to keep the water in a liquid form, and that being trapped under a sheet of ice makes sure it stays that way. Robert Tyler, an oceanographer from the University of Washington, has hypothesized that Jupiter itself generates large (underground) waves on Europa, which keeps the ocean heated.

"The modeling found that there could be a variety of different salts present on the surface but suggested that infrared spectroscopy alone is generally unable to identify which specific types of salt are present."

More recently, a study in April published by the journal Nature Communications speculated that life could exist in Europa's watery bodies precisely by inhabiting lake equivalents near the lineae that criss-cross its surface.

"Here we present the discovery and analysis of a double ridge in Northwest Greenland with the same gravity-scaled geometry as those found on Europa," the authors explained. "Using surface elevation and radar sounding data, we show that this double ridge was formed by successive refreezing, pressurization, and fracture of a shallow water sill within the ice sheet. If the same process is responsible for Europa's double ridges, our results suggest that shallow liquid water is [ubiquitous] across Europa's ice shell."

If nothing else, the newly-detailed images of Europa are further whetting researchers' appetites to learn more about the moon's many mysteries — and possibilities. And while Mars has been a fixation for astrobiologists, any life that ever existed there is almost certainly extinct — making Europa perhaps more intriguing than Mars in many ways.

"It's quite possible that Mars could have had life in the past, in a warmer-weather era, and it's possible that there are subsurface pockets on Mars that could have remnants of this living biosphere," Jet Propulsion Laboratory planetary scientist Cynthia Phillips told The Atlantic. "But on somewhere like Europa, life could exist there now."

Shares