One of the first things the coach who would ultimately change my life said to my team, the Cincinnati Marlins, when he started working with us in the late '60s was: "I'll be turning you into elite swimmers. If you do what you're asked, you'll do fine. If you don't, you won't survive."

In addition to miles and miles of what seemed like endless swimming, he brought in weights, and three days a week we also did a half hour of circuit training, which included bench presses, tricep extensions, and bent-over rowing with barbells. The other days we stretched and did dryland exercises. And I don't mean jumping jacks. At eleven years old, I did five sets of twenty military push-ups, five sets of twenty sit-ups, multiple squats with a teammate on my back, and concentric, isometric, and eccentric exercises with an Exergenie, a piece of equipment that was cutting-edge at the time and just beginning to be used by the NFL as a part of their training.

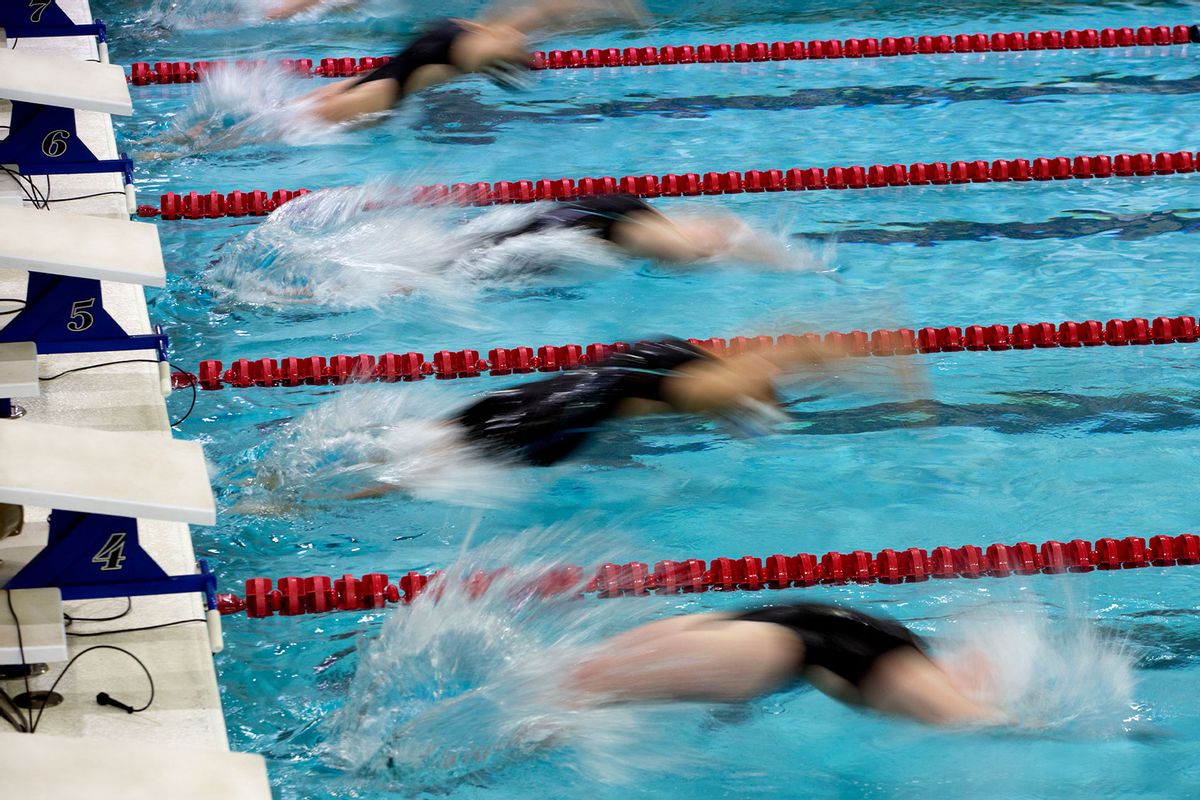

Once a place to have fun, swimming had become a place of hard labor, of following the rules and doing what we were told, of stretching the limits of what our bodies could endure. Our coach seemed to be redefining swimming as redemption through suffering.

Earning our loyalty was easy: we were winning, and we were proud. That put him in a powerful position.

And yet I continued, pushing myself through the constant pain of burning muscles and crippling fatigue. I followed the rules, even as the coach routinely pushed us to do things that seemed unfathomable and hurled kickboards, pull-buoys, paddles, and, worst of all, insults at us. I continued even when he prescribed us an extreme diet of 1,000 calories per day and began the practice of humiliating daily weigh-ins. I wasn't fat. Not even close. But I never paused to wonder whether his goals were justified.

Though I didn't realize it at the time, our coach had crossed the line to abuse. With my parents unaware and the team bringing in glowing athletic success — we were winning championships, going to Nationals and, some of us, even setting world records — I couldn't help believing that the coach must be right. Earning our loyalty was easy: we were winning, and we were proud. That put him in a powerful position.

Here are the things I now recognize that he, like other coaches, did time and again that allow them to cross the line to abuse without swimmers or parents giving it a second thought.

* * *

First, I had thoroughly brainwashed myself into believing he was right about everything, that he had no choice but to throw kickboards, or even stopwatches, to get some swimmers to listen. At the end of his daily lectures, he often would ask if anyone had questions and most of us would sit there, mute. I was scared to death to ask him anything. On one occasion when I managed to find the courage to ask a question, he chuckled and asked, "What is it, Twenty Questions?" –my new nickname—as if I were asking too much.

It wasn't until decades later that I realized it was the tough kids, the kids with the mettle, who got the kickboards hurled at them. These were the kids with a voice, and the hurled kickboards were a form of manipulation meant to silence and control them.

* * *

From the very first day, I didn't know if I trusted what our coach said, but I did trust his ability to instill fear. We swimmers all knew there were negative consequences if we didn't follow his my way or the highway approach. This became painfully clear the day we practiced in our 50-meter longcourse pool in the middle of a fierce thunderstorm. Despite parents' arriving in droves to pick us up, our coach continued to bellow: "Stay or you're off the team." As I remember, everyone continued to swim.

Even the parents put up with the yelling and screaming because all that fear had improved our times. And maybe he thought the discipline of losing weight helped swimming too; certainly, it seemed that losing weight meant to our coach that we were serious about swimming. How could I question him?

* * *

Even the coach's favorites weren't spared his wrath. When it came to daily weigh-ins, of course it was embarrassing to have to line up and have our weight monitored so closely and publicly every day. But I rationalized that this kind of discipline would help the few girls who had trouble controlling their weight.

When a swimmer didn't make weight, the whole team was punished. We rarely knew who was in trouble, and since the punishment never seemed to be directed at a single swimmer, it was somehow more tolerable and harder to peg as abuse.

* * *

As a thirteen-year-old, I was slow to develop physically and would use a shoelace to tie my bathing suit straps in the back so my suit would fit snugly. Our coach would tease that I was the only one he knew who wore a "turtleneck" bathing suit. He would constantly tell me I was uptight and needed to "stop worrying." He also liked to tell dirty jokes to the team in an effort to loosen us up before practice.

It took me decades to have the courage to state publicly that my coach's behavior was abusive and dangerous, scarring many of us for life. This is, in part, because this kind of abuse has been pervasive and ignored for years as a part of the swimming culture. When swimmers are breaking more records and swimming faster than they'd ever imagined possible, a totalitarian approach doesn't seem like a red flag.

But the important thing for coaches and parents to remember is that despite the immediate gratification of winning races and setting records, it is important to recognize when a coach crosses the line to abuse because the negative impact can have a devastating lifelong impact.

Shares