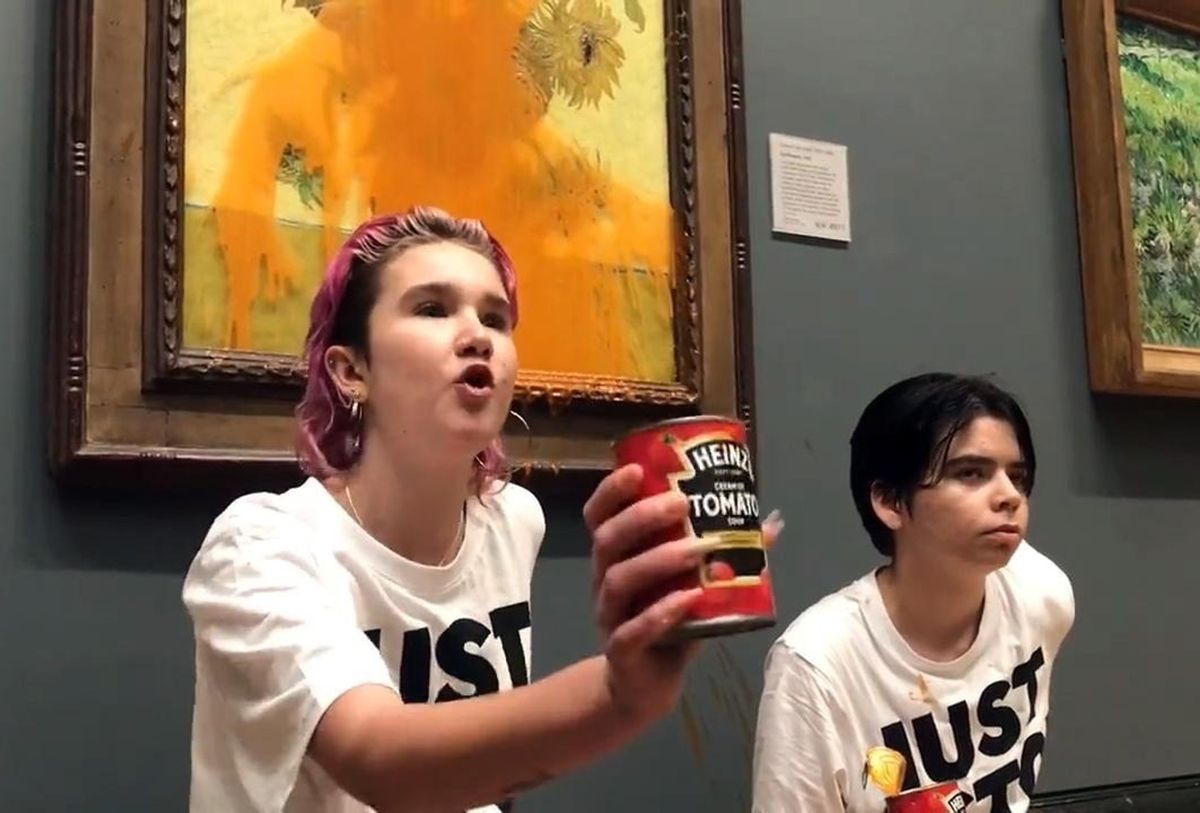

A pair of climate activists tossed a couple of cans of tomato soup on one of Vincent van Gogh's famous glass-protected paintings at a London museum on Friday, renewing a debate about the effectiveness of some of their group's strategies.

Phoebe Plummer, 21, and Anna Holland, 20—who glued their hands to the National Gallery wall after dousing the $84.2 million "Sunflowers" in soup—wore Just Stop Oil (JSO) T-shirts. The U.K.-based group shared footage of the action and their motivations on social media.

"Is art worth more than life? More than food? More than justice?" Plummer said in a statement. "The cost-of-living crisis is driven by fossil fuels—everyday life has become unaffordable for millions of cold, hungry families—they can't even afford to heat a tin of soup."

"Meanwhile, crops are failing and people are dying in supercharged monsoons, massive wildfires, and endless droughts caused by climate breakdown," the activist added. "We can't afford new oil and gas, it's going to take everything. We will look back and mourn all we have lost unless we act immediately."

The National Gallery and Metropolitan Police confirmed that "there is some minor damage to the frame but the painting is unharmed." The latter added that the protesters "have been arrested by Met police officers for criminal damage and aggravated trespass."

Some in the art and climate activism communities expressed support for the action.

French visual artist and environmental activist Joanie Lemercier declared that "art is absolutely pointless on a dead planet" and highlighted that the painting was not damaged by the protest.

Scottish historian and human rights activist Craig Murray initially said that "I support Just Stop Oil's direct action, especially the blocking of roads and refineries. It is needed to wake people up. But this is stupid vandalism, and counterproductive. This beautiful painting has no negative environmental impact."

However, Murray later added that "I was wrong about this. The painting is behind glass and unharmed. In which case, this is a very effective bit of campaigning for publicity."

Hyperallergic editor-in-chief and co-founder Hrag Vartanian said in a video that the ultrarich who are "buying and selling Van Goghs" are "the same people" who are on the boards of major polluting companies and "who are being feted by these museums."

While right-wingers worldwide seized the opportunity to paint the JSO activists as "crazy" vandals, other critics suggested that the soup stunt could damage efforts to bring more people into the global movement to combat the fossil fuel-driven climate emergency.

"They sure know how to get attention. And while their passion is admirable, their tactics are repugnant," said Mother Jones senior editor Michael Mechanic.

Two-Spirit Tuscarora (Haudenosaunee) television and musical writer Kelly Lynne D'Angelo said that "this is why y'all need to sit the f*ck down and listen to Indigenous people when it comes to climate activism."

The co-creator of the musical Starry about Theo and Vincent van Gogh, D'Angelo added that "destroying art—an extension of our humanity—is not the way. The piece is fine. But the damage to the spirit of it isn't. Ignorance wins."

American comic book artist Jamal Igle stressed that "this is not how you make your point. Luckily, the painting is covered in glass, so nothing was damaged and they'll probably be charged with trespassing. All you did was anger the very people you're trying to appeal to."

YouTube vegetarian chef Jerry James Stone had a similar message for the activists: "What a horrible way to express an important cause. This is beyond stupid, immature, and alienating. Grow the fuck up."

Social media content creator Matt Bernstein tweeted, "girl I'm down with the cause but Van Gogh was a broke, mentally ill painter considered a failure until his death, like what does he have to do with this," and contrasted Friday's stunt with some "effective" art-related actions.

Dana Fisher, a University of Maryland sociology professor who studies protest movements, explained to The Washington Post that actions like throwing soup at a multimillion-dollar painting are a form of "tactical innovation" to attract media attention.

According to the Post:

The media gets accustomed to particular types of activism; a march or a sit-in that once commanded attention soon gets written off as old news. Climate protesters, Fisher explained, started by gluing themselves to artworks, which initially made a small news splash. Now that attention for that has cooled down, they have moved on to at least the appearance of defacing artworks, in an attempt to attract more eyes.

The action in the National Gallery did make prominent headlines across U.K. newspapers and around Europe; by late afternoon, one video of the incident on YouTube had been viewed 13.3 million times. At least to the activists involved, the fact that the protest had gone viral was probably viewed as a success. The climate issue—which at times is buried by geopolitical, economic, and celebrity news—was back in headlines once again.

But as tactics escalate, protesters risk turning off people who may otherwise be sympathetic to their cause. "Research shows that this kind of tactic doesn't work to change minds and hearts," Fisher said. Someone prevented from commuting to work—or someone who believes that irreplaceable artworks are being harmed—might be turned off by the climate movement for some time, if not permanently.

"It's working to get attention," Fisher said. "But to what end?"

Al Jazeera noted Friday that "experts have predicted acts of so-called 'climate sabotage' will increase as extreme weather events such as droughts, wildfires, and storms proliferate and the urgency to act grows."

Daniel Sherrel, author of Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of the World, warned that such sabotage "would be a gift to the right-wing opponents of climate action, who would use it, leverage it for all its worth to accelerate their creeping fascism, make the issue politically toxic for moderate voters, arrest a generation of young climate activists, and sow division in the climate movement itself."

Damien Gayle reported from the museum Friday that "alienating people from their cause was a concern, said Alex De Koning, a Just Stop Oil spokesperson, who spoke to The Guardian outside the gallery after the room was cleared."

"But this is not The X Factor," the spokesperson said. "We are not trying to make friends here, we are trying to make change, and unfortunately this is the way that change happens."

Gayle also noted that "the canvas of the painting is protected with a glass screen, a factor Just Stop Oil said they had taken into account."

Writing for The Ecologist in July, Chris Saltmarsh—co-founder of Labour for a Green New Deal and author of Burnt: Fighting for Climate Justice—noted other recent cases of JSO activists "disrupting high-profile sporting events and cultural institutions," including gluing themselves to the frames of other prominent pieces of art.

As Saltmarsh detailed:

Targeting cultural institutions is not new within the climate movement. Since 2004, the Art Not Oil coalition has campaigned (with some notable successes) against oil sponsorship, taking creative protest to institutions including the British Museum, the Tate, and the National Portrait Gallery.

Just Stop Oil differs, though, in that their demand is generic and aimed towards the U.K. government rather than the subject of the protest.

Although Just Stop Oil is formally a distinct organization, this approach of general social disruption comes out of Extinction Rebellion. Initially, XR blocked roads and key junctions to maximize disruption. However, although they exist within the same tendency of the environmental movement, Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil now represent a strategic divergence with XR.

"Since its founding, XR strategy has evolved to target those directly complicit in driving climate change (e.g., fossil fuel firms, the Murdoch press, and financial institutions)," Saltmarsh wrote. "On the other hand, Insulate Britain and Just Stop Oil have respectively applied the approach of general social disruption to motorways or sport and culture."

"Some have criticized Just Stop Oil and Insulate Britain for alienating ordinary people from supporting radical climate demands," he added. "There's no evidence that this is actually the case. However, the real limitation of Just Stop Oil's strategy is that it tends towards marginality rather than building the power and mass movement we need."

Shares