When looking back through history to figure out how we ended up in this hellscape that will inevitably be known as the "Trump era," pundits often look to predecessors like Barry Goldwater in the 1960s, Richard Nixon in the '70s or even Ronald Reagan in the '80s. The 1990s, however, are often overlooked, even though that's when Donald Trump's notoriety as a tabloid fixture really came into focus. That decade is often remembered fondly these days, as a time of relative innocence, a country preoccupied with how to figure out email and what to do about a president getting a blow job in the Oval Office.

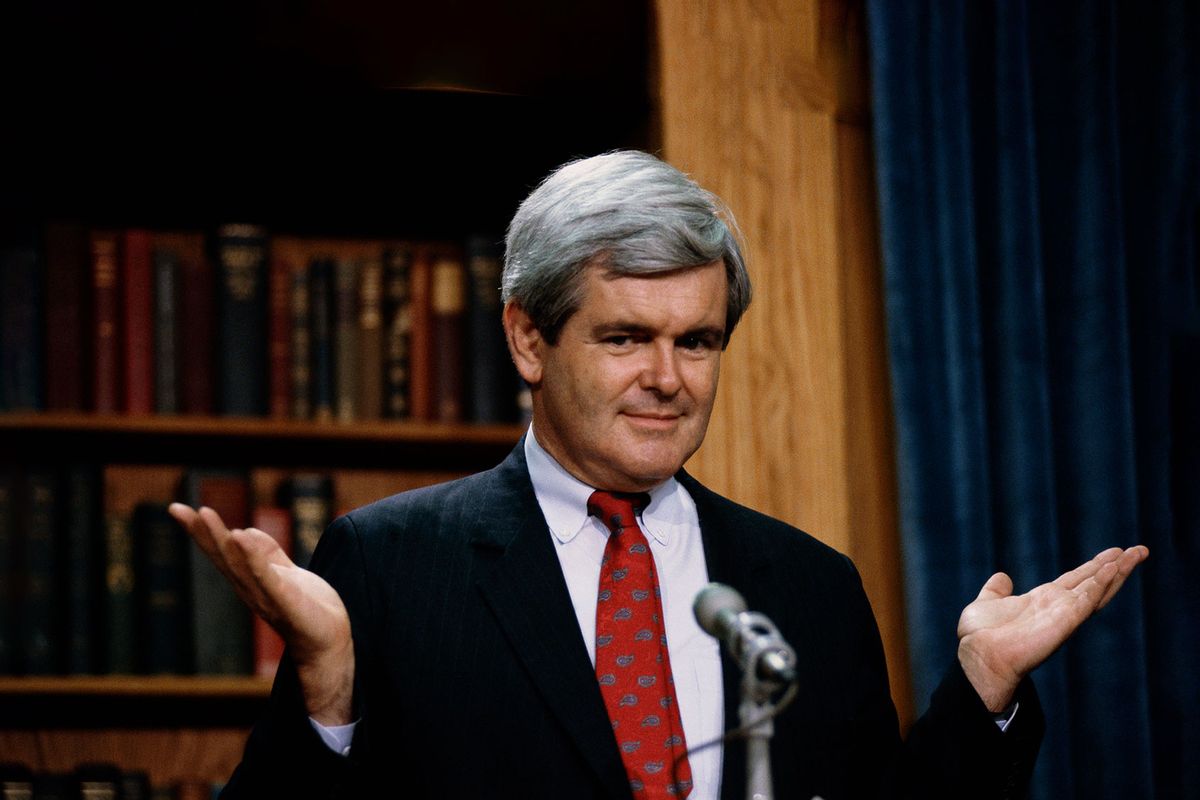

In her new book "Partisans: The Conservative Revolutionaries Who Remade American Politics in the 1990s," historian Nicole Hemmer wants us to take another look at the '90s. It was, she writes, "actually an era of right wing radicalization." And not just on the fringes, as with Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh. Led by figures like House Majority Leader Newt Gingrich and race-baiting gadfly Pat Buchanan, it was a time when the GOP stopped being merely a conservative party and forged its new path — a competitive race to the bottom in which the trophy goes to the most repulsive political troll. (Right now, it's Trump, but there are contenders, including Florida's Gov. Ron DeSantis.) That was when the idea of winning elections in order to govern wound down for Republicans and was replaced with scorched-earth politics, in which destroying the opposition is all that matters.

Hemmer spoke about her book and the dark side of the '90s with Salon. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The '90s: We like to remember it as a time of peace and prosperity. However, as you argue in this book, for the right, it wasn't just an era of increased polarization, but was "actually an era of right-wing radicalization." What do you mean by that?

In the 1990s, polarization wasn't a particularly good way of describing what was happening with the two major parties. Yes, the Republican Party was moving to the right, but the Democratic Party was moving to the right as well. So the parties weren't running away from one another in the way that we think of when we think of polarization. Instead, polarization was a tactic that was being used by Republicans to try to heighten the differences between the Republican and Democratic Party.

And because the Democratic Party was moving to the right, that meant that the Republican Party had to move even further to the right. A combination of right-wing politicians, politicians interested in polarization like Newt Gingrich, and a new media ecosystem helped to create a Republican Party that was much more radical, much closer to the far right and to violent extremism than it had been in previous eras. It was caught in a cycle that it would repeat in the decades that followed of constantly being pulled to the right by the most activist parts of the party.

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

I feel like we're in at least the third cycle of that, with the Tea Party being an example.

They had pushed for impeachment well before Newt Gingrich felt comfortable with it.

People are familiar with the ways that, for instance, [former House Majority Speaker] John Boehner was constantly being challenged by the Tea Party contingent of his party, who were threatening his leadership and acting as an obstacle for any type of legislating that he was hoping to do. But that was the same cycle that you actually see with Newt Gingrich.

We think, correctly, of Newt Gingrich as a radical figure, as a revolutionary figure in some ways. But he was constantly being challenged by a part of his party, a part of his House caucus that called themselves the True Believers. People like Helen Chenoweth. Lindsey Graham was part of this. They saw Newt Gingrich as too much of a swish. They constantly were threatening his leadership. They were trying to extend the government shutdowns even further. They had pushed for impeachment well before Newt Gingrich felt comfortable with it, and ultimately challenged his leadership and were not sad to see him step down after the 1998 midterms.

Why the '90s? Right-wing radicals have been chewing on the Republican Party at least since the 1950s. What was it about the '90s that they started to get the upper hand?

"Suddenly you have people like Pat Buchanan, who are arguing that maybe democracy isn't the best form of government."

This is a great question. So yes, there has been a strain of radicalism that has been absolutely foundational for conservatism in the United States. I don't want to undersell that. But there were some things that happened in the '90s that allowed them to become ascendant. One of them was the end of the Cold War. The Cold War provided both this kind of logic and this constraint on all of U.S. politics over the course of the 1940s to the 1980s. And it both opened up a space for this intense anti-communism and the Cold War conservatism that we're also familiar with.

But it also required people involved in politics to speak in the language of democracy and freedom and to, over time, capitulate to the idea that we should widen the electorate and make sure that people across the United States have the right to vote. When the Cold War ends, that logic goes away. Suddenly you have people like Pat Buchanan, who are arguing that maybe democracy isn't the best form of government, maybe those old constraints that had governed American politics for so long, maybe those weren't actually the proper boundaries for U.S. politics.

Even somebody like Ronald Reagan was a big supporter of open immigration to the United States. But you see a rise of nativism in the 1990s that was no longer constrained by this need to project a welcoming image to the world. But I also think that a couple of other things matter as well.

First, again, that new media environment. You had talk radio with Rush Limbaugh. You had the rise of cable news. You also had the experience of the Reagan presidency, which for some conservatives was really disappointing. It forced them to pay more attention to things like congressional elections, because they weren't sure that a conservative presidency was enough to enact the changes that they wanted.

You focus a lot on a lot of different interesting political figures in the '90s. But the three that really jumped out at me were Newt Gingrich, Pat Buchanan and Ross Perot. What about these three men were so important? How did they really define this changing GOP in the 1990s?

Newt Gingrich "was somebody who understood the importance of polarizing the electorate."

Each of them plays a different role. Pat Buchanan really was the person who had sussed out that there was an opening in U.S. politics, as he put it, to the right of Ronald Reagan. That by moving to the right you could activate a base of white voters to get engaged in politics and to join the Republican Party and the conservative movement in a way they hadn't before. He tapped into this kind of exclusionary racist white populism and helped to bring it into the Republican Party.

Ross Perot, on the other hand, is a very mediagenic person. He's an independent candidate. He's heterodox in his politics. He's opposed to the North American Free Trade Agreement, but he's in support of abortion. He's in support of gun regulation. He wants balanced budgets. He doesn't fit neatly in the two-party system. But as an independent, he attracts so many voters from across the political spectrum and really helps us to see how unsettled American politics were in the early 1990s.

Newt Gingrich was somebody who was, honestly, one of the savviest political operators in U.S. politics in the 20th century. He was somebody who understood new media. He was somebody who understood the importance of polarizing the electorate. That was his big complaint about Reagan — that Reagan had spent too much time governing and not enough time polarizing the electorate. He understood new media like cable. He was a big advocate of C-SPAN because it allowed him to get his message out over cable television.

He tried to attract the Perot voter through this kind of neutral, pragmatic language of reform. But he was constantly weaponizing it. He was somebody who understood the appeal of ethics reform and bipartisanship, and all these different things. But anytime he would touch those popular things in American political life, he instantly sought ways to use them as a weapon against Democrats. So he was somebody who understood the art of polarization in a way that I think did fundamentally transform U.S. politics going forward.

When I think of figures who kind of were central to the Republicans functionally losing their minds in the 1990s, I actually think a lot about Bill Clinton. Republicans just had an unhealthy fixation on him. There were these conspiracy theories that he and Hillary were murderers. In the book, you draw a clear line from the conspiracy theories to what eventually happened with the impeachment. Why Bill Clinton? What was it about him that made them lose their minds?

It's such a great question because you look back at Bill Clinton now, and he seems like kind of an anodyne figure, especially because he is a fairly conservative Democrat and somebody whose entrée into politics, particularly national politics, was about pulling the Democratic Party to the center. So you would imagine him in an alternate timeline as being somebody who worked very closely with Republicans and was able to foster a kind of bipartisan comity. That's not what happened.

In part, he was seen as a real threat. He was somebody who could tap into that populist anti-establishment fervor because he was this Southern Democrat. He was somebody who was a creature of Little Rock and not Washington, D.C. Yet at the same time there were these pictures of him and Hillary Clinton floating around in the 1960s and '70s, and so in a way he also epitomized all of the social and political changes of the 1960s. Hillary Clinton in particular. This idea that she might be a co-president, that she was a feminist, that she was somebody who used her birth last name, her family name, as her middle name. There were just so many things about her that said "feminist" in this way that the right really recoiled against. They saw a real opening to attack the Clintons as the avatars of the 1960s and 1970s.

"Even Bob Dole running in 1996 talked about the 'supposed' suicide of Vince Foster."

But of course, as you mentioned, they go well beyond that. That opposition, that threat of the Clintons, hits this new media environment of conservative talk radio, this extremely well-funded investigatory network that was devoted to creating conspiracy theories around the Clintons and to de-legitimizing Bill Clinton and Hillary Clinton. The combination of those things creates this fervor and almost this competition to see who can outdo the last person on the biggest scandal. You have people like David Brock writing for The American Spectator about Bill Clinton in Arkansas. But then you have the conspiracy theories.

The one that really takes off and sets the tone is when a close friend of the Clintons and a member of the White House team, Vince Foster, dies by suicide. That is immediately turned into a conspiracy theory of a cover-up [alleging] the Clintons murdered Foster in order to keep him quiet, and that takes off. You have members of Congress who are reenacting his suicide in order to try to prove that it's a murder. Even Bob Dole running in 1996 talked about the "supposed" suicide of Vince Foster. Very quickly, it gets into this feverish space and explodes in very well-funded conspiracy media. And you're right, it's not separate from the politics of the era. It's not even necessarily something triggered by Bill Clinton's radical politics, because his politics aren't that radical. But it feels very familiar for people who are experiencing politics in the U.S. today.

Want more Amanda Marcotte on politics? Subscribe to her newsletter Standing Room Only.

Speaking of the new media environment, it's hard to overstate how central Rush Limbaugh was in forming the conservative identity as we know it. In the book, you say people think a lot about Fox News, but in the '90s it was really Rush Limbaugh more than anything. What was it about him that made him so important? He remade the GOP in his image.

He absolutely did, and part of it is timing, and part of it is talent. He becomes a national host in 1988, not out of politics but out of radio shock jock entertainment. He was somebody who, unlike conservative media figures of a previous era, really knew how to entertain. He knew how to use airtime. He knew how to use the microphone. He knew how to use parody songs and little comedic bits mixed in with the politics of his show — nobody had seen anything like it before. For the right, that mix of comedy and entertainment and politics was instantaneously addictive.

Rush Limbaugh "was somebody who, unlike conservative media figures of a previous era, really knew how to entertain."

Within just a few years of his launch, he was on hundreds of stations, he was making tens of millions of dollars, but he was also a cross-platform hit. In the early 1990s, he has two bestselling books. He has a television show that Roger Ailes produces that launches in 1992 and runs for four years. He's also somebody who was willing to challenge the Republican establishment. He challenges George H.W. Bush.

So Bush invites him to stay overnight at the White House. He really works hard to get Limbaugh to say positive things about him, and Limbaugh ultimately does. He backs Bush in 1992. Bush loses, but people still thought of Limbaugh not just as an entertainer, but as somebody who was reshaping U.S. politics and really held power within the Republican Party. He becomes someone to whom the Republican Party not only feels it owes fealty but to whom it feels it owes deference. That gives Limbaugh first the appearance of power, and then actual power because Republicans refuse to cross him. There just hadn't been a media figure like that in U.S. politics before, and that's why he loomed so large over the 1990s.

One of the more interesting observations you make about Limbaugh, that I think a lot of people don't understand at this distance, is that he was able to walk an interesting tightrope. He was a shock jock who says the unsayable things, and yet somehow manages to always skirt away from the responsibility for racism, or misogyny, or anything like that. How did he manage to play that game so well for so long?

It's so fascinating, because you go back and you listen to him and you're like, "Oh. This is really racist, and misogynistic, and homophobic, and all of these things." But in part it was that combination of politics and entertainment and comedy. Whenever he crept a little too close to the line, to the extent that the line ever existed, he would say that he was just kidding. He would back away from it. There were bits that he did, especially in his early days, that he did drop. He had done these things called "caller abortions," which people felt crossed the line. So he stopped doing them. He apologized for this thing that he did called "The AIDS Update," which was not just homophobic, but especially cruel to people living through the AIDS epidemic.

He was also careful to package the more racist bits of his show as comedy routines. He had this parody song that he played in the late 2000s called "Barack the Magic Negro." This was a wildly racist parody song. But he would say it was parody. He would also point to a Los Angeles Times piece that had that as its headline. And even though obviously the Los Angeles Times piece had much more going on in it, Limbaugh used it to claim h was parroting and skewering the left.

Nowadays, we're enduring a moral panic over "cancel culture" and "wokeness." In the 1990s, the same thing was going on, but it was deemd to be a response to "political correctness." When you actually dig into the stories, it's either exaggerated or it's outright fake. These supposed excesses of the left are often not real, once you peel back the panicked overreaction. Yet it still manages to capture mainstream media attention. Why does this shtick keep working over and over again?

It really was a ripe environment for this lavish interest in political incorrectness.

If you spend any time looking at the "political correctness" language of the early 1990s, it feels so familiar and it feels so repetitive in many ways to what we're experiencing now. Part of it was that mainstream media outlets were hungry for this content. It was controversial. It was very easy to present a story that was full of these over-the-top examples that the conservatives often trotted out. And you wouldn't necessarily have to investigate them if you were a mainstream reporter. You could just report on what conservatives were saying about these various controversies, and that was enough for a story. It was a story that instantaneously had a sense of balance to it. You were showing that you weren't anti-conservative because you were giving airtime and credence to these conservative concerns in the 1990s.

And I think even among mainstream reporters, who were still largely a white male profession, there were shared anxieties and shared beliefs that there was an excess in a culture that had suddenly discovered sexual harassment, a culture that had begun to make space for women in the workplace, and for non-white people in the workplace, and in politics. It really was a ripe environment for this lavish interest in political incorrectness.

I think it's a lot of what we see today around the same cancel culture panic. There are plenty of people who are not at conservative outlets, who are in mainstream outlets, who share this belief that cancel culture has gone too far, share this idea that there is something suspect about the politics of the left, the politics of equity, the politics of equality, and the rise of women and people of color in the workplace. So we're seeing a lot of the same dynamics play out now.

Read more

about the impact of '90s politics

Shares