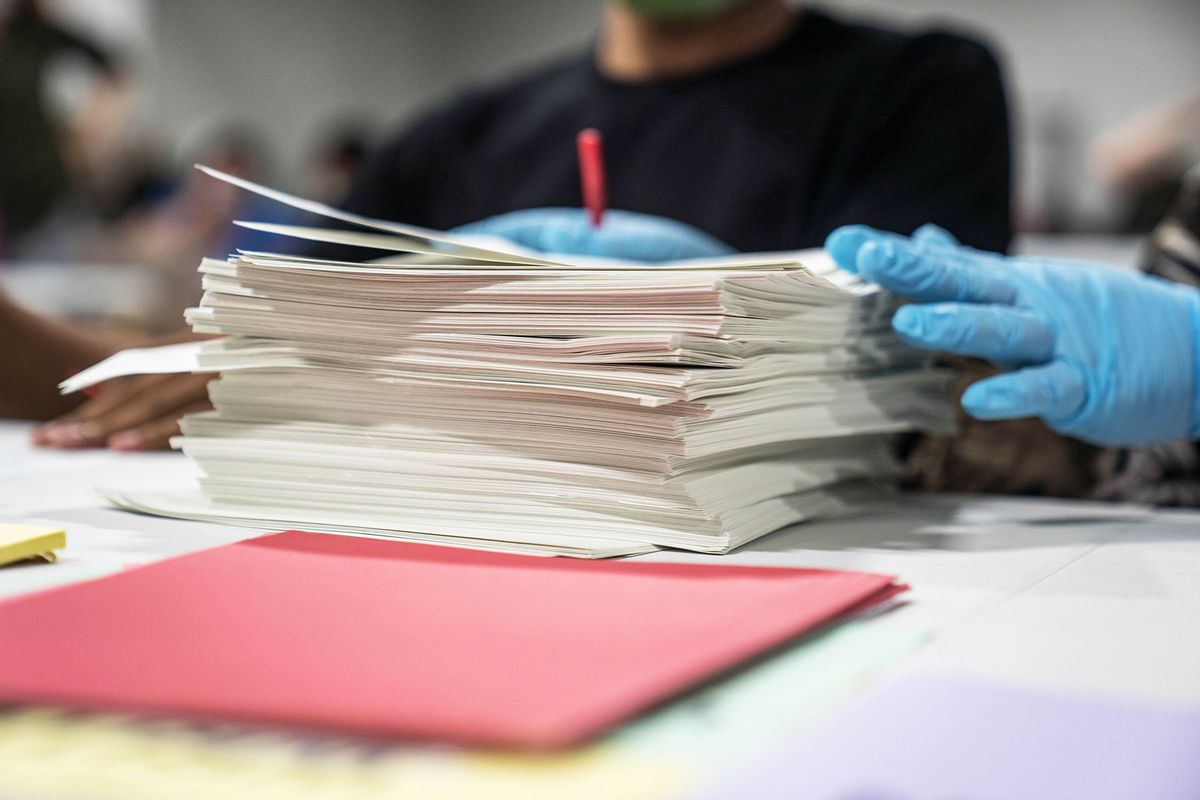

In what election experts call the latest effort to stoke widespread doubt about election security and the accuracy of vote-counting, Republicans in many rural counties are pushing to hand-count ballots in the upcoming midterms, despite no evidence of widespread fraud or voting machine irregularities.

Hand-counting is far less accurate than machine counting, experts say, and is likely to create errors and delay results by hours, days or even weeks.

In at least six states, Republican lawmakers have introduced legislation this year that would require hand-counting of all ballots instead of electronic tabulation. None of those bills have passed so far, but similar proposals have gained traction in some county and local governments.

Several candidates for statewide office, nearly all of them also prominent election deniers, are endorsing such efforts. Jim Marchant, Nevada's Republican nominee for secretary of state, said at a March county commission meeting in Nye County — a sparsely populated rural region of central and southern Nevada — that officials should "dispose" of all their electronic voting and tabulation machines.

"It is imperative that you secure the trust of your constituents in Nye County by ensuring that you have a fair and transparent election and the only way to do that is to not use electronic voting or tabulation machines," Marchant said.

Nye County, with a land area of more than 18,000 square miles and a population of roughly 54,000, plans to hand-count all midterm ballots in addition to using machine tabulation. In other rural Nevada counties, including Lyon, Elko, Esmeralda and Lincoln — all of which Donald Trump won overwhelmingly in 2020 — commissioners have introduced proposals to reconsider the use of Dominion electronic voting machines or get rid of them entirely.

Earlier this year, commissioners and election staff in Esmeralda County in southwestern Nevada (which has fewer than 1,000 full-time residents) hand-counted 317 paper ballots. The process took more than seven hours and was barely completed before the deadline to certify the results of the primary election.

Officials in Cochise County, Arizona, which is on the Mexican border southeast of Tucson, also voted in favor of hand-counting ballots alongside the official machine count. That could pose a significant logistical challenge; the county has roughly 87,000 registered voters.

Distrust of voting machines and electronic vote-counting has simmered in conservative circles for years, but became a major political force after the 2020 election, when Trump and his allies spread numerous conspiracy theories about Dominion and Smartmatic voting machines manipulating votes in favor of Joe Biden. No evidence has ever emerged to suggest that actually happened, or is even possible, and allegations that those companies had links to the Chinese or Venezuelan governments are categorically false.

Some Republican candidates, including Arizona gubernatorial nominee Kari Lake and secretary of state nominee Mark Finchem — both loyal Trump supporters and avid election deniers — have even filed a lawsuit attempting to block the use of vote-counting machines in the midterm election, claiming that the machines were not "reliably secure." A federal judge dismissed the suit for lack of standing in August.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

Mark Lindeman, the policy and strategy director at Verified Voting, a nonpartisan nonprofit that advocates for the responsible use of technology in elections, said that these efforts are part of a broader effort to discourage voters from trusting any part of the election process.

American elections "objectively are more trustworthy now than they have been in decades, but the fear-mongers are broadcasting the exact opposite," Lindeman said. Attacks on voting technology are "creating an environment in which some really dedicated public servants are leaving the profession because they're demoralized and in many cases afraid. That is a tragedy that injures all of us."

Dozens of states already conduct routine post-election tabulation audits, Lindeman added, checking the accuracy of vote counts. Virtually no significant problems or anomalies with machine tabulation have emerged in recent years. Voting and tabulation machines are always tested prior to an election, he said, to ensure they are functioning properly.

Jennifer Marson, executive director of the Arizona Association of Counties, echoed Lindeman's view. She explained that "there are numerous checks and balances built into the system" to make sure that the machines are tabulating correctly.

Despite the lengthy Republican-funded audit conducted after the 2020 election in Maricopa County, Arizona, which confirmed Joe Biden's narrow victory and revealed no evidence of fraud, the conspiratorial "narrative" about widespread voter fraud "persists for reasons that defy logic," Marson said.

"The folks who don't believe those facts are a very small, but very loud, minority," she added.

Research clearly indicates that vote tabulators are more accurate than hand counts, since humans are more likely to introduce error into the counting process. A 2018 study found that vote counts conducted by computerized scanners were, on average, more accurate than votes tallied by hand, as well as significantly faster.

"For people who have been led to radically mistrust elections, hand-counting the ballots won't do much good. They'll simply worry about something else."

The process of hand-counting ballots is also a complicated one, Lindeman explained. Even in a middle-sized county or municipality, thousands of people might need to be recruited and trained to count ballots on election night, and potentially over the following days. Furthermore, instead of using software that is specifically designed to tabulate and report election results, hand-counters must use spreadsheets to tally their results, likely making the process more confusing and introducing more potential errors.

Lindeman cautioned that a move to hand-counting will slow down the process dramatically, and is unlikely to reassure those predisposed to believe that elections have somehow been rigged or fixed. "For people who have been led to radically mistrust U.S. elections, hand-counting the ballots won't do much good," he said. "If their concerns about the machines are addressed, they'll simply worry about something else. I see this much more as an attempt to feed distrust of U.S. elections than to build trust."

The push for hand-counting ballots is just one aspect of a larger right-wing plan to undermine the "election infrastructure," said Heidi Beirich, co-founder of the Global Project Against Hate and Extremism. She linked it to related efforts such as sending out armed or menacing "poll watchers" to monitor early-voting sites, drop boxes and polling stations.

"I think it's going to be even worse when votes don't turn out the way election deniers want after the midterms," Beirich said. "Of course we don't know what's going to happen, but there could be harassment of vote-counters," both on election night and in the following days. "That happened in 2020," she observed, and may now be a permanent element of Republican electoral strategy.

Read more

on the fast-approaching midterms

Shares