In my career as a historian, I have learned in a personal way that being a witness to history is a two-way path. In one direction, encountering events and people from the past has enabled me to construct and refine historical narratives, to shine a scholarly searchlight on forgotten — or suppressed — stories. In the other direction, those moments of witness have insisted on their own power to teach and inspire this teacher.

The two-way nature of bearing witness — venturing out to explore but returning enriched — has most pointedly come home in four decades of work as a formal witness, an expert in court for more than a dozen Native communities across North America. That work has given me a faith in humanity and in our collective future, a faith I otherwise would never have known.

As an expert witness, my role has been to bring the experiences of this continent's first peoples into legal proceedings where their rights as tribal citizens and as Americans were being challenged. Here's a confession: I never adjusted to courtroom maneuvering and combat. Still, even in the rancor of litigious lawyering, I have had the privilege of compiling and conveying the special history of indigenous communities, of uncovering human stories that shaped a narrative marked by suffering, resistance and undaunted courage. The totality of that narrative has flowed back into my own life, demonstrating the insistent humanity of a people who were so often ignored or cast aside. These experiences that began in the role of an expert, reshaped me as a participant.

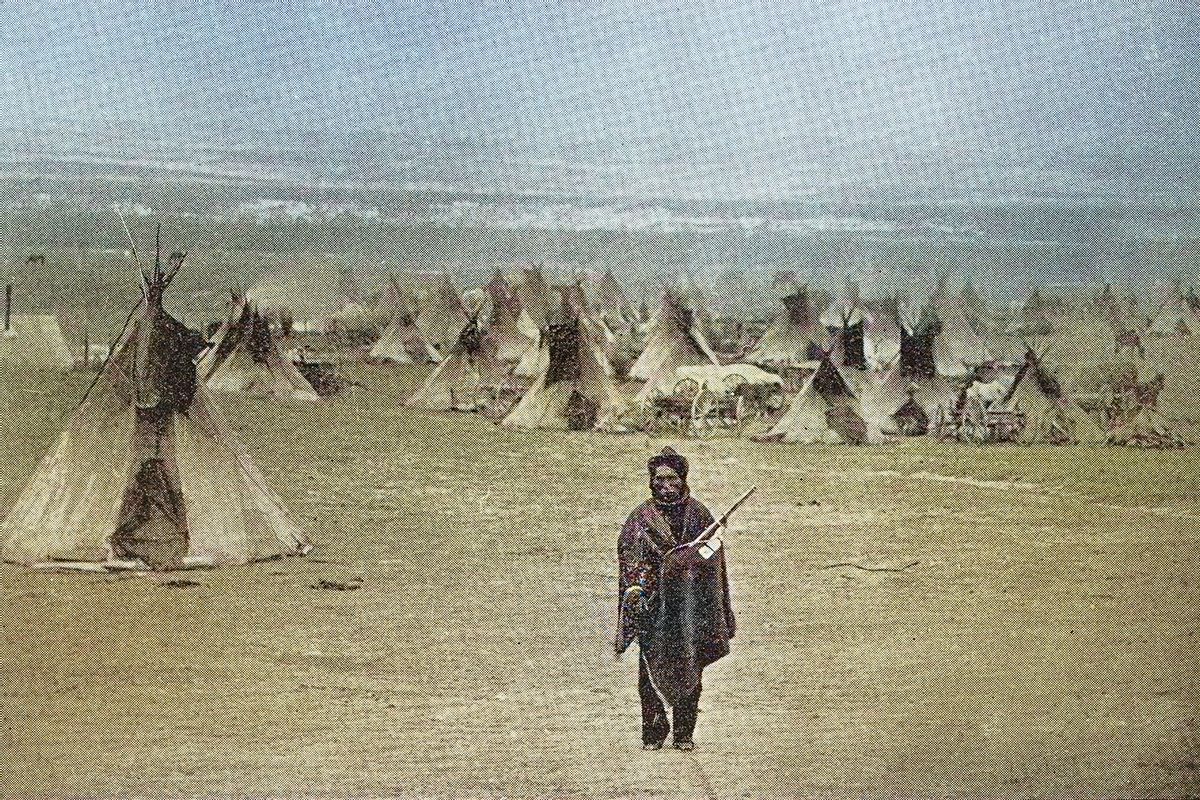

I unknowingly entered those dual roles in 1977 when I was asked to be part of a case arising from a challenge to the boundaries of the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation in central South Dakota. A group of white political leaders incensed by the rise of assertive Native leaders in the "Red Power" era had embarked on a campaign to limit the reach of tribal governments. At Cheyenne River, they claimed that a 1905 act of Congress, which made a portion of the reservation eligible for public homestead entry, had implicitly "diminished" the reservation. By chance, lawyers in the Department of Justice learned that a part of my recently completed doctoral dissertation in Indian history included a discussion of such "homestead laws." A white academic with no experience in Indian country, I was suddenly an expert.

I spent the next several months in libraries, the National Archives, local courthouses and on the reservation. I set out to interview every octogenarian who might know and recall something about the law's passage and implementation. It turned out that the woefully deficient "agreement" with the tribe that Congress had deceptively used to justify its action was signed in the middle of winter, a time when few snowbound tribal members would leave their homes to attend the negotiations. Most had no idea that any changes were about to occur. But my research drew me beyond surface facts.

In my interviews on the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation, elder Raymond Clown told me that his family came out of their cabin one morning to discover Norwegian-speaking homesteaders unloading a wagon in their front yard. His family's experience was typical: government officials barely mentioned the new law to the tribe. Future decision-makers with authority over education, health care and other services never acknowledged the homestead areas or recognized a change in reservation boundaries. Clown's testimony invited me to imagine events from his family's point of view.

On the Cheyenne River Sioux reservation, elder Raymond Clown told me that his family came out of their cabin one morning to discover Norwegian-speaking homesteaders unloading a wagon in their front yard.

It was joyful and humbling when my interviews and research ultimately became part of the record in a unanimous Supreme Court decision that vindicated the tribe's position, defended ably by both their attorneys and lawyers from Justice. When the ruling issued, I understood that to the extent I had contributed to the tribe's remarkable victory, it was likely because they had shared with me a quiet truth, one that I had learned from personal interviews that encouraged me to look deeply into the records I located in the archives: The people of Cheyenne River viewed their reservation as the central instrument that oriented them to the world.

Here's what was most inspiring: The barely comprehensible legal language and daily government bullying the people at Cheyenne River had endured — both in the past and in the present — did not even come close to intimidating them. They swatted away the attempts to divert them from their way of life like so many pesky mosquitoes.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

In Iron Lighting, a remote farming district the tribe's opponents argued lay outside the reservation's boundaries, Thomas Elk Eagle sat across from me at his kitchen table and recounted his life as a rancher, farmer and tribal citizen, a life that stretched back to the beginning of the century. Like Ray Clown, who had had no understanding of why Norwegian immigrants suddenly appeared in his front yard, Elk Eagle never turned for a second from his commitment to living out his life in his Native homeland. His courage and generosity enabled me to understand how the past appeared to him and his family.

John Hump kept me on the edge of my seat—and long beyond the life of my battery-powered tape recorder—as he described the government's indifference to his family's complaints of trespass and invasion. Telling his story in his cabin near Cherry Creek, he gradually drew family members into the living room. By the time he ended, dozens of relatives and neighbors had shared in his testimony. And the inadequacy of the opposition's simple, legalistic case came clear.

I had gone to each of these people — and many more — to assemble my expert report, but the very force of their stories compelled me to grasp, and witness, their indomitable dedication to their land. By sharing their stories, the elders at Cheyenne River gave me more than historical insight; they helped me understand and admire how Native people view the universe and their lives. They conveyed to me their allegiance to their families and their homeland.

The elders at Cheyenne River gave me more than historical insight; they helped me understand and admire how Native people view the universe and their lives.

The learnings they shared nourished and sustained me through a long and satisfying career in pursuit of proper memory and some measure of justice: as I explored the history of voting rights on a reservation in Montana; investigated the chicanery surrounding 19th-century treaty making in Michigan; studied the persistence of tribal life in a supposedly-abolished reservation in Minnesota; or compiled the story of how a small group of Oneida Indians near Green Bay, Wisconsin, worked to uphold a treaty that local people wrongly argued had no force.

Native Americans face enormous obstacles when they enter U.S. courtrooms. Despite an impressive record of recent victories, they can count on few legal principles to sustain them. To cite but one example, no legislation affecting American Indians has ever been found unconstitutional.

And yet, in the right circumstances, the courts have heard Native testimony, and experts communicating their perspectives, that cannot be ignored. That hardly means that Native people always, or even consistently, prevail. But as one minor actor in the drama to protect their lives and ways of living, I have been honored with the opportunity of helping to bring their voices into the courthouse. Again and again Native people have been ready and willing to reverse the typical direction of research — from scholar to subject — by teaching me the central truths of their past.

In human relations, and particularly in a democracy committed to the rule of law, listening to and appreciating the experiences of others leads inevitably to connections in our common humanity. Once we recognize and embrace that connection, it is impossible to retreat into caricatures or to dismiss people others have viewed as history's victims.

The privilege of listening to American Indians' stories and struggles, and of conveying them in courtrooms and classrooms over many years, has filled my journey with purpose. More than that, it has created a deep faith in the enduring presence of Native people in America and their immeasurable contribution to it.

Shares