Paulina Porizkova, one of the world's most well-known faces and an early supermodel for many brands, joined me on "Salon Talks" to discuss her new collection of essays, "No Filter: The Good, the Bad, and the Beautiful." The book, which Porizkova says is not exactly a memoir, but reads a bit like one, begins with a foreword by her publisher at Open Field, Maria Shriver.

Porizkova says Shriver reached out to her about a collaboration during the first wave of COVID when she was stuck at home in the countryside. The model and writer was then determined to complete a full book in a very short period of time on topics she had spent years thinking about, particularly her experiences coming up in the height of '80s and early '90s supermodel popularity and the psychological and physical challenges that came with being objectified as a teenager.

In sometimes gritty detail, Porizkova shares her early experiences as a displaced child of war from Czechoslovakia, which included being separated from her parents and growing up in a rather fast fashion. Later, she met her future husband Ric Ocasek, front man for The Cars, with whom she raised two sons in spite of an obvious age difference. The 25-year relationship was not, however, without significant challenges fueled by fame and media scrutiny. Porizkova writes in candid and moving detail about the public fallout from Ocasek's sudden death several years ago, including the shock of being cut out of his will.

The author, who says her book was written without a ghostwriter, has penned many widely published essays and quite a few books over the years, but none were as emotionally challenging and freeing as this one. It was, she leads off with, the introspection and freedom that came with accepting her status as the "crying woman" on Instagram in 2021, that made her finally relatable to millions of followers who saw her as an aging beauty willing to stand up for real women and the experience of getting older and feeling discarded by society because of it.

Porizkova shared with me that she hopes that women, and all readers, find some hope and light in her stories and see parts of themselves exposed and accepted for who they really are, without judgment and with kindred support. Though she and her late husband used to spend a lot of time judging others with cruel scrutiny, she says, Porizkova pivoted and completely changed her perspective once she became the subject of the same by others in her grief. Now, she spends her time shedding light on the negativity this breeds, hoping she can help "be the light." Watch our "Salon Talks" interview here or read a transcript of it below.

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

A good place to start is with Maria Shriver, whose imprint your book was published with, Open Field. Shriver said that you were "uniquely qualified to write in real time about the different challenges women face throughout life's various phases — aging with honesty, coping with loss and identity, finding a renewed sense of mission and purpose, using your voice to inspire others as they deal with some of the same issues." What was the impetus for "No Filter" and why now?

Maria's the one who came to me. She actually just called me out of the blue and said, "Hey, I follow you on Instagram and I really love what you're doing, and would you write me a book?" I had gotten a lot of offers for a tell-all memoir, obviously wanting to get the dirt on what happened in my life, which I was not willing to do. But when I spoke to Maria and she said to see it more like her own book that she had written, "I've Been Thinking," which was more like devotionals. And I have no idea what a devotional is. I don't even know what an essay is, quite frankly. I had to learn how to write them really quickly. But I thought, "Oh, that I can do, because that's like when I write on my Instagram. I can just go more in depth and I can flesh it out and I can really sort of sink into a space where I can get it all out." So it inspired me, and I thought, "Yeah, absolutely, I want to do this." And then I went to the jungle, did a reality show, which completely messed me up.

Yes, I've seen your Instagram chiropractor pictures of you getting realigned after not eating and sleeping.

Doing extreme physical challenges every day for four hours straight with no sleep and no food. I kind of messed up my hips a little, and when I came back I couldn't walk. What better time to write a book in three months? So that's how that came about. So many things in my life seem accidental. It feels like sometimes it gets thrown at me, but it all benefits me to learn more and be a better person and just become a bigger person, as all learning does. But so much of it seems not to make sense until it's already long gone. I think that's probably true for everybody.

"I don't have to push women off in order to be the only one standing."

You mentioned that in the book and how you and your late husband were both very judgmental. It was a way of building yourself up, but now you have chosen to intentionally lead with love and to be open and accepting, regardless of how you may have felt before. Is that one of the biggest growth opportunities you've had?

I think this is certainly a thing that has made me a much better person now than I was even probably 10 years ago. That was something that I was learning not because of his death and not because of all the stuff that happened subsequently. This was something I was learning when we started to separate and I started realizing that the way we had been living was extremely isolating and very lonely, and this high mountain that we had set our hut on was a really windy and lonely place.

It was a conscious choice when he was no longer my, well he was always my north star, but when I didn't so fixate on him always being right and me always being wrong if I felt differently from him, where I thought, "Oh wait a minute, I don't have to be judgmental. I don't have to push women off in order to be the only one standing." That's not even a very nice way to live. It was obvious, I mean, it took me a while to discover that, but that was when we were separated, that was with just the understanding that how isolated we have made ourselves.

Speaking of the industry, you write a lot in your book about society's expectations of girls being women and women looking like girls, particularly in the advertising and the editorial magazine business. As you got older and felt, as you wrote, more invisible, both at home, I think you described yourself as a coffee table.

Yeah, something that you put things on.

And outside, despite your continued beauty, how did you reconcile this for yourself? Because many women struggle with aging largely because of societal expectations, and certainly most of us are not some of the most famous models in the world.

That's you assuming that I have reconciled it, and I don't know that I have. This is something that I'm still working my way through. I'm half just really annoyed by the idea and the concept that our faces are somehow wrong for being their age. What's wrong with my age? What's wrong with being 57? What's wrong with looking 57? Why is 20 superior to 57? I'd really like an answer to that. Why is youth so sought after and so treasured in our society? Because besides fertility for women, it doesn't really do much else. That's literally the only benefit of youth. Everything else comes with age.

I was told that I was in my prime 30 years ago, when I'm like, "Uh-uh, I'm in my prime now. As a human being, I'm in my prime now. The fact that you can't see that I'm beautiful is not my problem, it's yours." Then the other half of me that's going, "Oh my God, everybody my age looks better than me now." We comparison shop all the time. I'm like, "Oh, well, she doesn't have the bags under her eyes, and she doesn't have the forehead wrinkles."

Then you have to pay for that, and not just financially.

But the rewards of it is that you get to stay at the table a little longer, you get to participate a little longer, you are not as quickly dismissed. Because if you are a 50-something-year-old woman who looks 39, you're celebrated for aging well. So, yes, of course, what woman doesn't want to be called attractive? I mean, so much of our lives growing up since we were little kids, we were told that our value, much of our value laid in how attractive we are. And then if you are lucky enough to be judged attractive, it's got a limited time span and you get the pretty privilege that comes with it. Of course, it all happens when you're a child, so you don't really understand it. And then you age out of the privilege, and you go, "Wait, why? Why did I age out?" Because it's still the same face technically with some life signs on it.

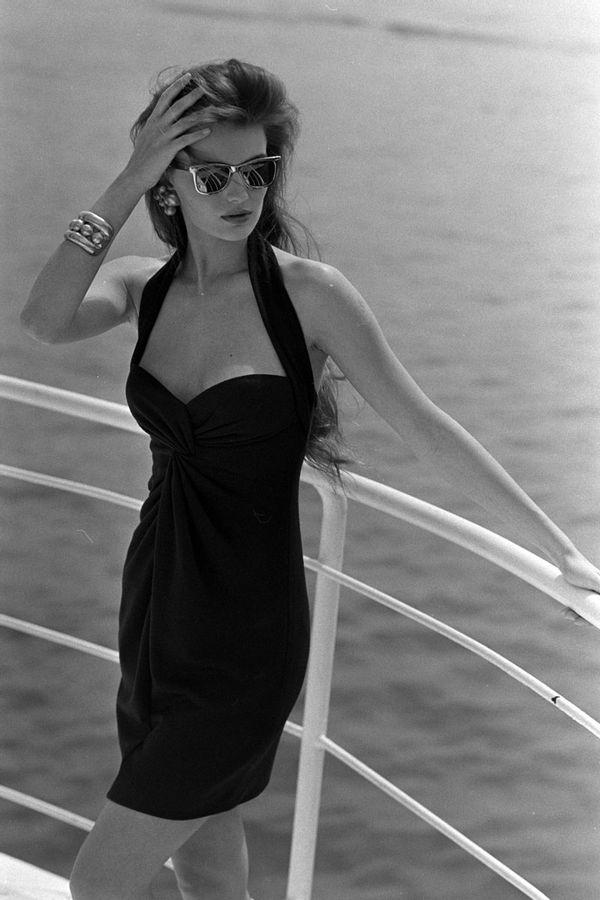

Paulina Porizkova modeling for Anne Klein Resort 1987-1988 Ready to Wear in 1987. (George Chinsee/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images)

Paulina Porizkova modeling for Anne Klein Resort 1987-1988 Ready to Wear in 1987. (George Chinsee/WWD/Penske Media via Getty Images)

I saw some of your 2019 Sports Illustrated shoot, and of course I'm not a dude looking at a pinup magazine, but I really couldn't see any sign of significant difference in how you look in those pictures versus when you were doing the covers. Sure, things settle a little, but to me, you still look great. You still look the same. How do those conversations go? Does your agent still call you and say, "Hey, do you want to do SI again?" Or are you fostering these relationships where you're like, "You know what? I'm pissed that people are telling me on Instagram I shouldn't take my clothes off anymore." Is it you or is it them?

Oh, it's always them. You know that. You know you don't have decision-making [power] in the fashion world. I can't go to somebody and go, "I would like to do a shoot." "People, I'm available. I am." Doesn't quite go like that. No. The Sports Illustrated came around again because of my Instagram, because I was posting bikini shots. And I guess MJ Day had thought, "Oh, OK, she still looks OK."

To that point, I have observed that an increasing number of brands are wisely trying to attract a larger advertising demographic and more dollars from women who don't look like you. It is becoming more accepting, in certain silos, of more differently sized, differently able models.

You're right. There's so much more inclusivity in the fashion world now than when we were 15, where you kind of had to be a fairly specific kind of model. There's body positivity and there's all different shapes and sizes and far more inclusion for people of color, all great. I'm all for it. Represent all women, yes, please.

But who is still not super represented? My age. Your age. Women who are in their 50s, even late 40s who look like their age. That's the little catch. It's like if you are that age, but you look younger, you're cool. You're aging gracefully. JLo is not a day over 39. I mean, gorgeous, absolutely beautiful, and that's how you're supposed to look when you are 52. That is the final frontier to me now. It's like, "Oh, well, you've done body inclusivity, you've done inclusivity of people of color, even gender, more fluid with the genders and more allowance for all of that. Great. Now let's expand it to us women who actually buy the product." But I think this is where that little thing comes in, the little "but" is, but we have to buy it.

I think women our age don't necessarily want to buy from women their age. I think it's the same reason that you will go have Botox and fillers and a little facelift. You want to look younger because in order not to be invisible, you have to look younger, so you will buy younger. You will buy a wrinkle cream from a 17-year-old and you will buy a Chanel suit from the 25-year-old, hoping that it's going to do the same for you. Of course, until we stop buying into that, it's not going to change because, of course, it's where the money is.

Having been in the fashion industry myself as a young teenager, like yourself, I know of what you write in the book, sadly, about the experiences that you had with men in particular, gay or straight. By the way, you note that the idealized vision of a woman is not necessarily impacted by sexuality. Has the business changed since then? We women were always called girls in the business — always sexualized, fetishized.

We're still called girls. This freaks me out. Not to interrupt you, but I just did a shoot, I did a model shoot the other day last week or something. The stylist was just touching me up or something, and she said, "Oh, you older girls." And I just went, "That's right. We're never called women, never. It's always us girls." And now I'm apparently an old girl.

That's what they call cows and old horses, right?

"Sexual harassment was, to me, compliments, until my late forties. I didn't even realize that that's how I had assembled it, cobbled it together."

Uh-huh.

You're an old girl. And you just stand there when this happens? Do you make conversation? Or are you just like, "It's not worth it"? Because it's so ingrained in the industry.

Well, for me it's just like, yeah, it's so ingrained, and it's not meant in an offensive way. It's just how people speak in the business. They still speak that way. It's still "girls." You're still, when you're on set and you're a model, it doesn't matter if you're 100, then you'll be the old girl. It's just what people are used to. It's the status quo. I wasn't offended. I just thought, "Ooh, ooh, that's so interesting. That fits, actually, that really fits in what I was saying in my essay, about we were always called girls, and apparently we still are."

Has anything changed for the better?

That I do not have the authority to be able to say because when I model, it's clearly that I'm an older woman. I'm modeling as an older woman, and I'm Paulina Porizkova. I'm not just some random model from Ohio now that they can treat any old way, so people are really, really nice to me. I do know that that's not necessarily the case everywhere. It's a special treatment that I'm getting, so I really can't tell, and modeling has so much, it's sort of pulled away so much from the model and into the land of the celebrities and the influencers and all that. You're not going to mistreat a celebrity, and you're not going to mistreat an influencer because they're going to out you.

I do think that things must have changed because we actually now have a voice. We can reach an audience instantly, which we never could. The only way that we got an audience was being taken a picture of and then translated through a page. And that's how you were shown to the world. You actually never even had a voice. You were a paper doll. And now, we all have social media, and we all have a voice. So I think a lot of things don't fly anymore.

Coming to the fore of Me Too, you write pretty early in the book that a photographer walks up to you when you're a young girl and takes out his penis and puts it on your shoulder when you're sitting there in the makeup chair. And you don't even know what it is for a minute. I had this moment where I was like, "We really do get PTSD from this industry." I know very well the amount of, if not outright assault, then the kind of negative attention that is focused on young models and had quite a bit of that myself. And you said, "If you didn't get that attention," you wrote, "You felt less than." You're like, "Wait, why aren't they harassing me? I must not be the A girl anymore." So it's so complicated. When people question why you became this crying woman on Instagram, I would make an educated guess that it was perhaps much more than just your personal life. Can you talk about how you've been affected for all time by your experiences that were negative and what you've done to try to reframe those?

Sexual harassment was, to me, compliments, until my late 40s. I didn't even realize that that's how I had assembled it, cobbled it together. I think I was watching an Oprah episode with my girlfriend, who was also a model, and it was about sexual harassment in the workplace. And at the end of the episode we looked at each other and we went, "Sexual harassment, that's compliments." And then we both went, "Oh, how F'd up is that, that we don't know the difference?"

"When I was in middle of my grief and my really dark days, I remember so desperately wanting to read a book that would sort of hold my hand."

That's because we were children. That's how we were shaped. We were shaped into believing that this is the way the world is because it was the way it was for us. Look, it's very hard for me to disentangle the specifics of the modeling and the fashion world and the things that I took away from that and the experiences of my childhood that brought me into the fashion world, that made me react a certain way in the fashion world and then take that away from my long marriage. It's all intricately woven together, like I think lives are. There's nothing very clear-cut about. And this is what happened here, it's all integral and woven together.

Paulina Porizkova during a promotion for Estee Lauder in 1988. (Dick Loek/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Starting really early, my parents abandoning me sort of primed me for this, to be this girl that needed to be validated by other people. In this world, when you're finally told that you are beautiful and that you matter, and then consequently the celebrity that came with it, like, "Oh, everybody loves me. Everybody wants to know what I'm having for breakfast." You confuse it with love because it's the attention, the attention you've been wanting your whole life. All of a sudden it's like attention is thrown at you from everywhere, and you feel important, and you feel loved, and you don't understand that it has nothing to do with you, that it's other people's perceptions of you. It's the way other people look at you. That conditioned me to fall for the one man who would love me with a kind of possessive and obsessive quality to make me feel like he really cared and I really mattered. And so I lost myself in the marriage. I mean, it's all intertwined.

It is all intertwined. Well, I did mention the crying woman, and you write about that and how you realize that that's what people were calling you. You're in a bar, and somebody comes up to you is like, "Wait, you're that crying woman." And you touched on it a bit earlier how social media, particularly Instagram, had given you and a lot of us a voice where you didn't have it. It no longer diminished you to a beautiful face or body. Can you talk a little bit more about that and what the space to speak, share, reach people and work through some of your own stuff really created for you?

I literally reached out on Instagram because my husband died. I had no money. I was stuck in a big old house out in the country with nobody, and it was COVID, and I was drowning. I was desperately needing some light, just somebody to hold my hand, and there was nobody available to hold my hand. My friends were all having their own problems, and you couldn't see anybody. Throwing my vulnerabilities out there, I didn't know who they were going to reach or that they were going to reach anybody. It was literally little "help me" messages in bottles that I just tossed out into the ocean.

The surprising part of it was that I wasn't alone. I wasn't alone. There were other women that felt like me. There were other men that felt like me. There were people who had great amounts of empathy and would hold your hand online on social media. One would tell you, "Things will get better." Then lots of women that shared their own stories about their husband's passing or divorces and connecting and metaphorically holding each other's hands across the internet. So again, my throwing up a photo or a video of myself crying wasn't with the intention of, "Oh, this is going to make a splash."

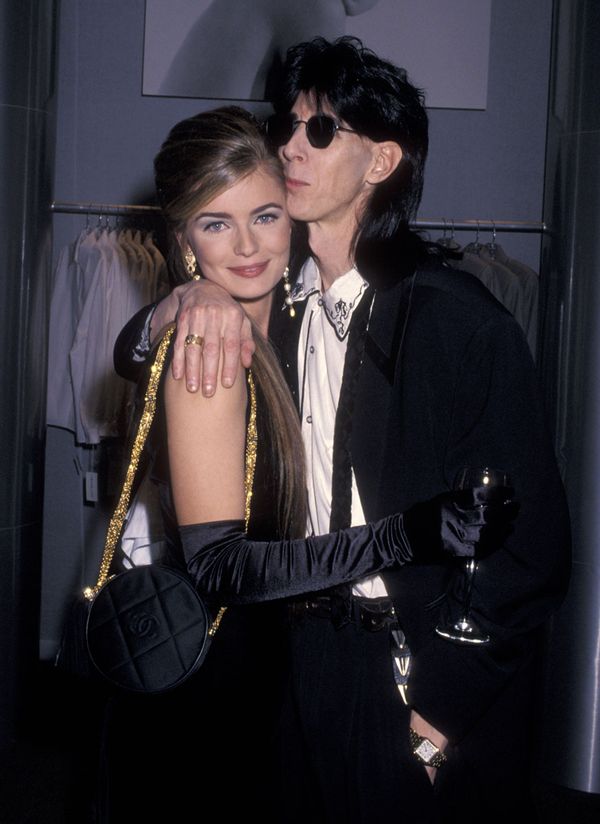

Musician Ric Ocasek and model Paulina Porizkova attending "CFDA Vogue 7th on Sale Fashion Benefit for AIDS" on November 29, 1990 at the Armory in New York. (Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

Musician Ric Ocasek and model Paulina Porizkova attending "CFDA Vogue 7th on Sale Fashion Benefit for AIDS" on November 29, 1990 at the Armory in New York. (Ron Galella/Ron Galella Collection via Getty Images)

No, I understand. You're looking for a connection.

Yes, exactly.

Some time has passed, and thankfully it seems like quite obviously you're doing better, and you're feeling good. The tenor of your posts has changed, as I am thrilled to see. So what is Instagram offering you now?

It's kind of remarkable because I really do interact with my Instagram. Everything that I post is done by me. I don't have an assistant that is putting stuff together and posting it. I read all the comments pretty much daily, and I respond to many, so I am intimately connected to these people. I've made friends from Instagram. I have a whole bunch of brand new friends because of Instagram. And there are people that come up over and over that I know have been with me for two years or three years. I know their names, and I know who they are.

It's like a community. It's like going to a community center. It's connection. And it's connection on a level of these people now sort of know who I am. They know that I am a human being. I'm not a paper doll. Oftentimes, just they're being supportive as in, "Yay, go Paulina. I'm proud of you. You're doing great. Your picture is beautiful. Can't wait to buy your book." All of that stuff. And then of course the inevitable trolls, and they'll go on there and say something terrible, which I find mostly funny.

You've written a lot of essays over the years and a few books as well, so people may not know that you're quite a prolific writer.

I wouldn't say prolific, but I am a writer. It's funny because when I signed a deal with Maria, and it was put out that I'm writing a book from Maria Shriver, there was a lot of, and this was journalists, little quips about, "Paulina Porizkova is going to attempt to write a book for Maria Shriver."

"I was being told that I was in my prime 30 years ago, when I'm like, I'm in my prime now."

Oh, that's mean.

How many people that have published a novel, a children's book, op-ed pieces, and magazine pieces would you say are attempting to write?

Was this harder or easier than some of the other things that you've written? Because you really do have to go through the mental mill of, and I find as a writer, when you're reliving a story, if you're trying to capture it for other audiences other than your own brain and your therapist maybe, it's really hard. It's like reliving the trauma, and there's some catharsis to that. On the other hand, that's a good thing. And yet the process of, I've got done a book, it's really hard, especially if you're writing about your own experiences. I just wondered how this was for you.

Well, thank you for asking me as a writer to writer. It was actually really easy. It's funny because my novel took five years. That was a lot of creating a world and thinking up characters and what character serves which part of the story and where is the story going and all of that sort of groundwork before it becomes something. This one, literally, it fell out of me because I had been experiencing and thinking about nothing else for the two years preceding me writing this book. This was all my brain contained. I didn't have any other thoughts.

So when I sat down, it literally was that opening the vein at the typewriter, writing is easy, you just open the vein. It was that. I opened the vein, and I bled out all over the page, and that's what it did. I wish it was, although it's a little gory, there is a sort of letting go, putting it down, letting it out. And post writing the book, I think I feel more at ease. I feel more at peace because I feel like I got to say what was boiling inside.

What do you want people to take away from your essays? Because I think if you write with intention, personal or professional, there's always a hope that it'll reach someone.

I've been actually asked this question before, and I thought, "Oh, my intention, wait, what? Did I have an intention when I went into writing this besides can I do it in three months? This is a challenge. Can this be done?" I didn't really go into it with a specific intent. Having written it though, I think because this was what was so heavy for me to carry at the time, at the moment, was for people to listen to other people, basically. It's just be aware that your friends, people that you don't know, people that you do know, might be suffering and just be a little kinder, hold their hand. Just because you assume people are doing well, doesn't mean they are doing well.

I think a lot of it, now that the book's out, now that I've gotten feedback from women, one of the most rewarding things have been when women come to me and they take out passages that meant something to them in the book. Out of 10 women, it was 10 different passages, which made me so happy because I thought, "Oh, I didn't know anybody was going to pay attention to that. And I didn't know anybody was going to pay attention to that." It was so incredibly rewarding. But that's not why I wrote the book. I think of just barely everything else in my life, I wrote a book because somebody challenged me to do it.

Much as you said, you found relationships on Instagram, where people found what you were saying resonated with them on a number of levels.

When I was in middle of my grief and my really dark days, I remember so desperately wanting to read a book that would sort of hold my hand. A book that would help me navigate, a book of somebody that had written something that somehow resembled me, that mirrored my experiences. And I couldn't find any. I read Joan Didion's, "The Year of Magical Thinking," and there was a couple of grief counseling books. But there's not a whole lot of literature out on that.

Society, we're so afraid of death, and we're so afraid of grief, and we're so afraid of vulnerability. I remembered how much I needed it when I was in that spot, and so I sort of wanted to do it. It's kind of like my Instagram. I want to see women with my face, meaning I want to see women with their age plainly written on their face. And if I don't find a lot of them, then well, I'll put it out there then. I'll do it. So this book, I suppose, was written in that way, with that intent. There you go. To be the candle for somebody else that I didn't have.

Watch more

"Salon Talks"

Shares