A constitutional republic is a precious and often precarious thing. That is as true in the United States today as it has been elsewhere and at other times in history. This week has added new evidence of those realities.

It began with Donald Trump's online musings about "terminating" the U.S. Constitution because he didn't like the results of the November 2020 presidential election. That provoked so much blowback, including from Republicans, that he tried to walk that radical idea back two days after the Dec. 3 Truth Social post in which he first floated it.

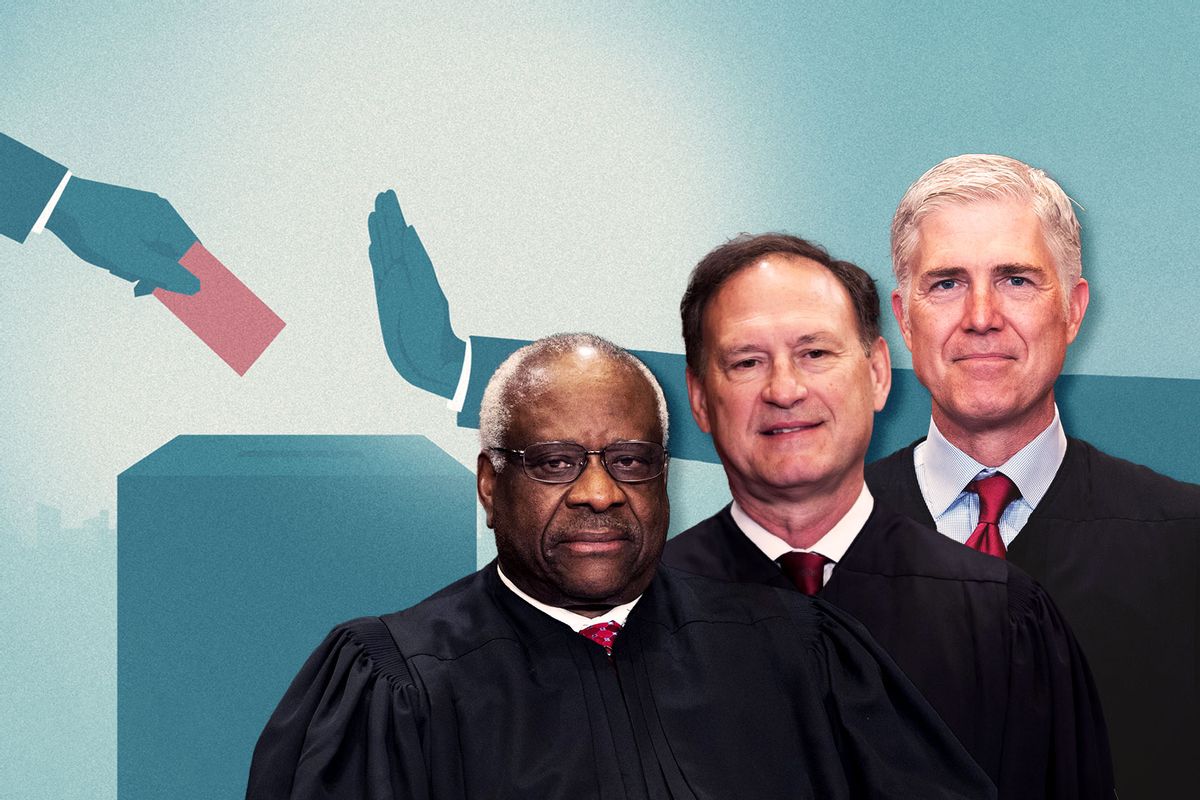

Then, on Wednesday, three Supreme Court justices appeared poised to use the case of Moore v. Harper to neuter the scheme of checks and balances around federal election rule-making in America.

To see the connection between Trump's willingness to trash the Constitution for his own narrow political purposes and the court's consideration of the Moore case, we need to look closely at the forces propelling and financing the right's authoritarian political ambitions.

Trump's threat to "terminate" the constitution was more overt and grabbed the headlines, but the Supreme Court's forthcoming decision in Moore may prove far more consequential for the demise of democracy.

Moore v. Harper raises a fringe, ultra-conservative legal thesis — the "independent state legislature theory" (ISLT). If adopted, it could grant state legislatures virtually unlimited power to set the rules for federal elections. During the Dec. 7 oral arguments on Moore, questioning from Justices Neil Gorsuch, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas reflected their clear sympathy for the North Carolina legislature's extremist ISLT position.

If their position prevails, the American people's right to choose their representatives could be disastrously compromised.

Moore involves a harshly gerrymandered congressional map that North Carolina's Republican-controlled legislature adopted in 2021. The state's Supreme Court struck it down under the North Carolina constitution. Republican legislators are now asking the Supreme Court to embrace ISLT and rule that state courts have no say over legislative actions in federal election matters.

None. Nada. Whatever the legislature says is state law, pertaining to federal elections, is the law. Full stop.

Wow.

First year law students learn that in 1803, in the seminal case of Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall established the power of judicial review — the principle that courts ultimately determine "what the law is." The judiciary is the central check on renegade politicians wielding raw legislative power.

Recall the quip attributed to Mark Twain that "No man's life, liberty or property is safe while the legislature is in session."

Or, as James Madison put it in his argument in Federalist 55 about the need to limit legislative power: "In all very numerous assemblies, of whatever characters composed, passion never fails to wrest the scepter from reason. Had every Athenian citizen been a Socrates, every Athenian assembly would still have been a mob."

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

While Marbury involved the federal judiciary's authority to invalidate legislation, the identical role of state courts is embedded in state constitutions across the nation. And those courts frequently invalidate acts of their legislatures on state constitutional grounds.

In North Carolina itself, in fact, the state's legislature has expressly given state courts the authority to invalidate redistricting maps like the one at issue in Moore.

In other words, legislators in the Tar Heel State were for judicial review of gerrymandered maps before they were against it.

ISLT advocates cite Article I, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution, which says that the "Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof," subject to override by Congress.

The Supreme Court's activist, conservative majority is untroubled by violating long-established precedents — when they get in the way of its substantive political ends.

Similarly, Article II, Section 1 governs how presidential electors are selected. It says, "Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct," a slate of electors to represent the people of that state and cast their votes in the Electoral College.

But ISLT doesn't just undermine checks and balances as a fundamental constitutional principle. It also runs squarely into a wall of Supreme Court precedent.

Long ago, in McPherson v. Blacker, a case involving the means through which a legislature prescribed choosing electors, the high court stated, "The legislative power is the supreme authority except as limited by the constitution of the State."

In 2015, the court rejected an ISLT-type claim that only the state legislature — and not voters, through the initiative process — could determine how redistricting maps were drawn.

And consider Chief Justice John Roberts' 2019 majority opinion in a case on partisan gerrymandering, in which he recognized that legislative gerrymanders did not operate in a vacuum. State constitutions, Roberts said, "can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply" in gerrymandering cases. (Roberts did not tip his hand during Wednesday's arguments.)

Of course, the Supreme Court's activist, conservative majority is untroubled by violating long-established precedents when they get in the way of achieving its substantive political ends. In such circumstances, it tosses out precedent like used tissues.

Indeed, the threat to constitutional governance posed by the ISLT and the possibility that the court may disregard its own precedents is so great it has raised alarms even among conservative legal luminaries. Retired appeals court icon J. Michael Luttig's commentary on the Moore case is entitled, "There is Absolutely Nothing to Support the 'Independent State Legislature Theory."

And as Judge Luttig told the New York Times, Moore is a case "with profound consequences for American democracy."

Similarly Ben Ginsburg, the Republican election lawyer par excellence, wrote that ISLT threatens to intensify discord and disinformation about elections and whether they can be run fairly. Ginsburg warns that its likely effects include exacerbating "the current moment of political polarization and further undermining confidence in our elections."

Similarly, the Conference of Chief Justices, which represents supreme court justices of every state, submitted an amicus brief in Moore renouncing ISLT.

Who do we find on the other side? Among ISLT supporters is infamous Trump crony and former law professor John Eastman, whose bar license is under investigation in California and Washington, D.C.

So what's going on with the signals on Wednesday showing three justices leaning into ISLT? Pursuit of right-wing power.

Just look who's behind the ISLT claims. According to the nonpartisan watchdog group, Accountable.US, reactionary dark money groups have donated $90 million to advocacy groups supporting the Republican legislators' claims in Moore.

Leading the pack with $70 million is Donors' Trust, a PAC led by Federalist Society co-chair Leonard Leo, who runs another conservative nonprofit that recently attracted an unprecedented $1.6 billion donation from a single ultra-wealthy donor who hoped to enlist Leo to drive the judiciary to the extreme right.

As we know from the decisions that this Supreme Court has already made removing the guardrails on dark money, voter suppression and anti-democracy measures, adopting rules that favor the powerful is high on the conservative justices' agenda. They plainly hope to use those rules to keep Republicans' minority party in power indefinitely, if not to help Trump himself.

You don't need to read the tea leaves to see where the court's far-right wing wants this to go. Just follow the money.

Read more

about the Supreme Court's recent momentous cases

Shares