Timing, as the old saying goes, is everything.

This maxim, which applies to so many ordinary activities, has special purchase in the extraordinary world of America's death penalty.

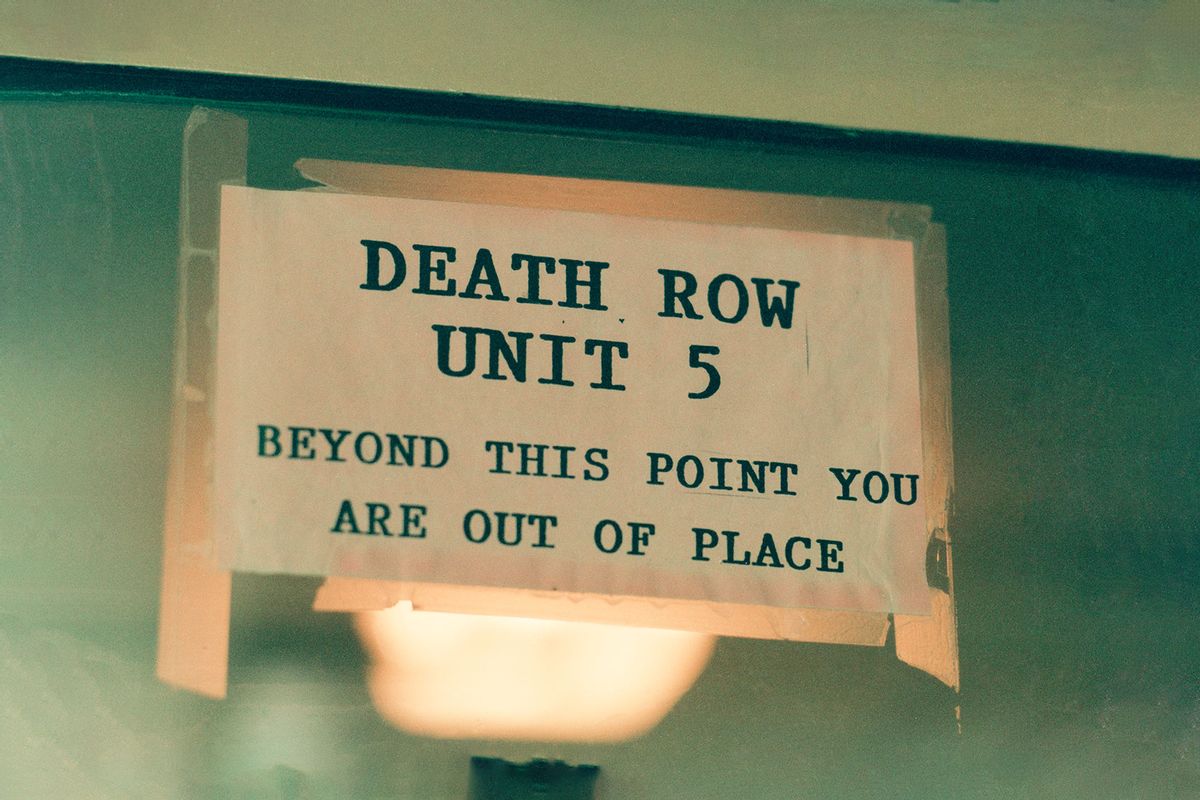

In that world, courts use filing deadlines to deny hearings or to consider even meritorious claims in death cases. Stays of execution are sometimes issued at the last minute to prevent miscarriages of justice. And execution protocols often specify a series of mandatory steps during the preparation for an execution, as well as when they must be taken.

Death warrants, which authorize the state to kill someone convicted of a capital crime, generally establish explicit time frames within which an execution must be carried out.

Without those time frames, the execution process could become even more drawn out and torturous than it already is. Without them, an important control over that process would be removed.

That is why the Alabama Supreme Court's Jan. 17 order giving the governor complete discretion over the period of time during which a death warrant can be carried out is so disturbing.

Previously, the court, which has the authority to issue execution warrants, required officials from the state Department of Corrections to complete executions within a 24-hour period specified in the warrant itself. If an execution goes awry, as they have frequently done in Alabama and elsewhere, and cannot be completed within that period, officials must call it off and ask the court to set a new execution date.

The court changed this requirement in response to a request from Gov. Kay Ivey, a Republican and longtime death penalty supporter.

She made her request in the wake of several botched executions in Alabama in which people condemned to die endured cruel and torturous treatment. Last fall, the executions of Alan Miller and Kenneth Smith had to be called off when execution team members could not set the IV lines needed to carry the drugs that would kill them after having jabbed the men repeatedly with needles.

In both cases, the only thing that saved Miller and Smith from even more torturous treatment was that corrections officials ran out of time before the midnight deadline specified in the two men's death warrants.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

As the Montgomery Advertiser reports, Ivey told the state Supreme Court that "officials are often under a 'time crunch' to carry out executions, and spread the blame between the condemned for challenging their sentence in court; the 6 p.m. start time for executions required by ADOC's (Alabama Department of Corrections) current protocol; and the longstanding Alabama Supreme Court rule limiting execution warrants to a single 24-hour period, which Ivey called 'perhaps the most significant aspect of this problem.'"

The governor further explained that "This court rule is what requires Department of Corrections officials to stop all execution attempts at midnight on the scheduled execution day," and told the judges that ADOC Commissioner John Hamm was "'evaluating options' to change the execution protocol to start at an earlier time and 'will be making a recommendation to me shortly.'"

Ivey herself identified two alternatives that she said would provide greater flexibility to officials charged with carrying out executions. First, death warrants could set a longer period for the execution to be carried out. Second, they could allow that period to be extended in the event of a court-imposed stay of execution.

"I prefer this second option," Ivey told the court, "Ultimately, I trust your judgment as to the specifics of the amendment. My only request is that you move as expeditiously as prudent given the importance of this rule change to the administration of justice in our State."

In its Jan. 17 order, the court went well beyond what Ivey had requested, effectively transferring the power to control the time during which an execution can be carried out from the court itself to the governor.

The order says that the court "shall at the appropriate time enter an order authorizing the Commissioner of the Department of Corrections to carry out the inmate's sentence of death within a time frame set by the governor, which time frame shall not begin less than 30 days from the date of the order," but does not specify how long the timeframe set by the governor may be.

This is a radical departure from existing practice in this country. According to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), an advocacy group, "Most states require executions to be scheduled on a specific date."

The Alabama Supreme Court's surrender of its own authority over executions is a radical departure from existing practice — and opens the door to unconstitutional and unethical cruelty.

In Utah, for example, the law requires that death warrants, which are issued by trial judges, must "state…the appointed day the judgment is to be executed, which may not be fewer than 30 days nor more than 60 days from the date of issuance of the warrant, and may not be a Sunday, Monday, or a legal holiday. The Department of Corrections shall determine the hour, within the appointed day, at which the judgment is to be executed."

Although some states, such as Georgia and Florida, do not require that the death warrant specify a single day for the execution to occur, they set a limited time period within which the death warrant is valid.

In Georgia, like Utah, trial judges are authorized to issue death warrants. But Georgia law says that "The time period for the execution fixed by the court shall be seven days in duration and shall commence at noon on a specified date and shall end at noon on a specified date."

In Florida, the governor issues death warrants after the Florida Supreme Court informs them that the person sentenced to death has filed all legal claims and appeals. As in Georgia, Florida death warrants are valid for a seven-day period.

Until the Alabama Supreme Court issued its order, as the EJI notes, "No other jurisdiction in the country allow(ed) for executions to be scheduled during a 'time frame' without a specified range of time that has been clearly established and reviewed."

Moreover, as the EJI suggests, what the Alabama Supreme Court has done may run afoul of state law, since the legislature delegated the authority to set execution dates to the state supreme court, not to the governor.

The broad grant of authority to the governor raises the prospect that inmates could be subject to endlessly torturous procedures during executions. It gives state officials license to continue their negligent and cruel execution practices and proceed with even the most gruesome executions until the inmate is finally put to death.

As the EJI concludes, "The practical effect of allowing an execution to be carried out during an undefined 'time frame' instead of a specific date is that the state could continuously attempt to execute condemned prisoners like Kenneth Smith for hours or days."

Such a prospect surely violates the Constitution's prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. "Punishments are cruel," former Supreme Court Justice Harold Burton once observed, "when they involve torture or a lingering death." Cruelty, he said "implies … something inhuman and barbarous, something more than the mere extinguishment of life."

The Alabama Supreme Court may share Gov. Ivey's impatience and frustration with what they regard as legal niceties that prevent botched executions from being completed. But it has not done what the Constitution requires, namely to ensure that if a state wants to carry out executions, they do not become gruesome spectacles of suffering and lingering death.

Read more

on capital punishment in America

Shares