A pterodactyl with some especially weird teeth was recently discovered in Southern Germany, shedding new light on the behaviors and diet of these ancient flying reptiles.

With nearly 500 hooked teeth, new research published in the German journal Paläontologische Zeitschrift describes Balaenognathus maeuseri, a pterosaur (Greek for "winged lizard"), as stalking through prehistoric swamps and using freaky denticles to filter-feed on shrimp, small crustaceans and other tasty snacks. Some 152 million years ago, during the Jurassic age, this B. maeuseri died near a village in Wattendorf, Bavaria, a German region best known for its castles, alpine landscape and beer. But Bavaria also boasts a fantastic fossil trove in the laminated limestone of its basin. The limestone is called laminated, or sometimes plattenkalk, because it is layered in flat sheets that intricately preserve fossils in incredible detail.

The plattenkalk has yielded many different species, including ancient fish like coelacanths and theropod dinosaurs. In fact, the very first pterosaur fossil ever described comes from this region. In 1784, the historian and naturalist Cosimo Alessandro Collini was the first to describe a pterosaur, a fossil heaved from the same kind of Bavarian limestone as B. maeuseri. Collini, once a secretary to Voltaire, was one of the first scholars in the Age of Enlightenment to recognize fossils as the petrified remains of ancient eras. Back then, it was common to assume fossils were evidence of the Genesis flood narrative in the Bible.

But Collini was completely confused by this creature, thinking it was a bat-like marine monster. It wasn't until Georges Cuvier, a French paleontologist, came along that it was correctly recognized as a flying reptile. Some 240 years later, we're still making remarkable discoveries about pterosaurs from Bavaria. But B. maeuseri is unlike anything ever found before.

"The jaws of this pterosaur are really long and lined with small fine, hooked teeth, with tiny spaces between them like a nit comb," David Martill, the study's lead author and a professor of paleobiology at the University of Portsmouth, said in a statement. "The long jaw is curved upwards like an avocet and at the end it flares out like a spoonbill. There are no teeth at the end of its mouth, but there are teeth all the way along both jaws right to the back of its smile."

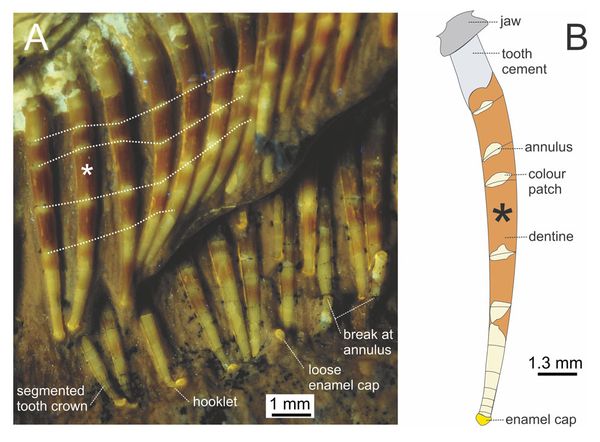

"What's even more remarkable is some of the teeth have a hook on the end, which we've never seen before in a pterosaur ever," Martill added. "These small hooks would have been used to catch the tiny shrimp the pterosaur likely fed on — making sure they went down its throat and weren't squeezed between the teeth."

The bones of Balaenognathus maeuseri, found in the slab of limestone. (Photo courtesy of PalZ)

The bones of Balaenognathus maeuseri, found in the slab of limestone. (Photo courtesy of PalZ)

Up close, the teeth resemble spindly plant roots or mealworm bodies. The specimen has about 480 of them, which forms a grid similar to the huge plates of baleen that certain whales have in their jaws. Often a yellowish-white, baleen is not actually bone but keratin, the same substance in your hair and fingernails. Baleen whales will gulp up water teeming with ocean critters, then filter the water out through their baleen. Any crustaceans, shrimp, fish or whatever left behind becomes a meal for the whale.

B. maeuseri presumably got its dinner in a very similar way, but also more flamingo-like, rippling tentatively through the shallows, slurping up mouthfuls of lagoon water and filtering out the pond scum. The first part of its name, Balaenognathus, even means "whale jaw," a reference to this feeding style. The maeuseri part refers to one of the co-authors, Matthias Mäuser, who passed away during the writing of the paper.

This is the only specimen of B. maeuseri to exist (which isn't uncommon in the fossil record to only have one sample of an entire extinct species), but it was almost completely missed.

The specimen was accidentally uncovered while moving a large block of limestone containing ancient crocodile bones. But when discovered, it had already been broken into a slab of 17 chunks. Small fragments of the specimen were "prospected" using ultraviolet lights at night. Thankfully, this particular limestone preserves really well, so it had mostly clean breaks and wasn't difficult to piece back together. Only a few fingers are missing. Still, during preparation some of the teeth "popped off," as the authors put it, and had to be glued back in place. Otherwise, the skeleton is remarkably intact. Clearly, this poor pterodactyl has been through a lot.

B. maeuseri is currently on display at the Bamberg Natural History Museum in Upper Franconia, Germany.

Fig.A: UV close-up of the tooth section at the narrowest point of the funnel. Fig.B: tooth preservation shown in the interpretative drawing of an isolated tooth. (Photo courtesy of PalZ)

Fig.A: UV close-up of the tooth section at the narrowest point of the funnel. Fig.B: tooth preservation shown in the interpretative drawing of an isolated tooth. (Photo courtesy of PalZ)

Shares