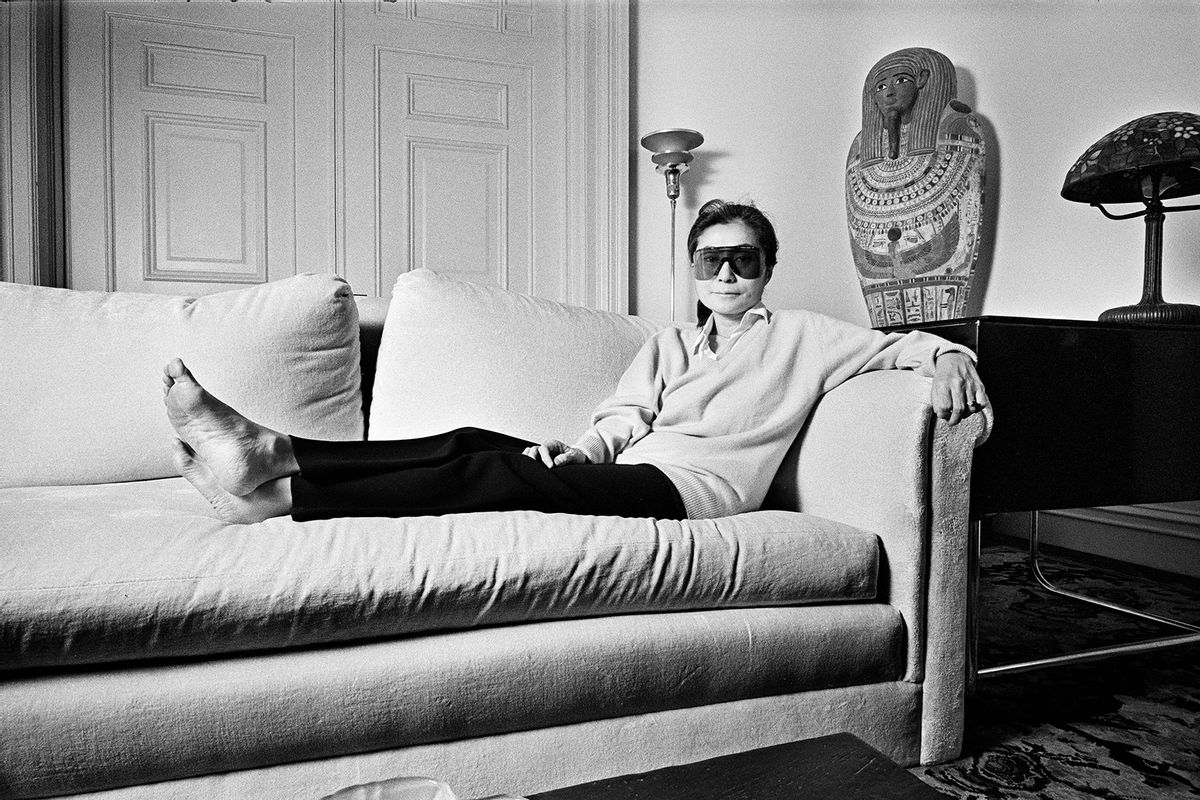

Today is Yoko Ono's 90th birthday. Since the late 1960s, John Lennon's widow has served as a lightning rod for the ire of an overly large coterie of Beatles fans who would come to blame her for the group's disbandment. In many ways, this rabid disgust can be attributed to unchecked misogyny, even racism, whose animus can be traced to an abiding disbelief by certain fans that Lennon could actually love someone like Ono, preferring to believe, it seemed, that she had somehow beguiled him.

In September 1980, during the final weeks of his life, Lennon confronted this issue, admitting his frustration to journalist David Sheff. "Anybody who claims to have some interest in me as an individual artist, or even as part of the Beatles," he remarked, "has absolutely misunderstood everything I ever said if they can't see why I'm with Yoko. And if they can't see that, they don't see anything." Incredibly, not even Ono's unfathomable trauma at having witnessed her husband's senseless murder would quell the naysayers and detractors who disparage her name.

As we celebrate Ono's ascent into the ranks of the nonagenarians, we can perhaps more profitably honor her aesthetic contributions by ignoring her detractors and highlighting her artistry. By the time that she met Lennon in 1966, Ono had successfully established herself amongst the Dadaesque group of artists known as Fluxus (from the Latin word "to flow").

Ono had begun exhibiting her performance art in such works as "Cut Piece," in which she reclined onstage while audience members cut off her clothing with a pair of scissors until she was naked. During the summer of 1966, Ono left New York in order to attend the "Destruction in Art Symposium," an international congress that Fluxus was hosting in London. Before long, she took to hanging out with the gaggle of hipsters who frequented the Indica Gallery. It was there that she met Beatle John on November 9, 1966.

This was groundbreaking stuff, particularly during a hyper-masculinized era that wasn't necessarily prepared nor ready to take responsibility for its, at times, emotionally dehumanizing practices.

As a way of introducing her upcoming exhibition at the Indica, which would be opened to the public the next evening, Ono handed Lennon a white card embossed with the word breathe. "You mean, like this?" he responded, before breaking into a pant. Almost immediately, Lennon found himself enjoying the humor behind her art. Following the diminutive Japanese woman around the gallery, he happened upon a ladder, above which hung Ono's "Ceiling Painting." "It looked like a black canvas with a chain with a spyglass hanging on the end of it," Lennon remembered during an RKO Radio interview on the last afternoon of his life.

At the top of the ladder, John peered through the magnifying glass at the canvas, which sported a single word: yes. Years later, Lennon would fondly recall that "that's when we connected, really." While they wouldn't become a couple for another 18 months, the die had been cast. "We looked at each other," he recalled for RKO Radio, and "something went off."

Working in partnership with Lennon, whom she married in March 1969, Ono expanded her multimedia artistry to include songwriting and rock 'n' roll musicianship, no doubt fanning the flames of her critics in the process. By 1973, with her marriage to Lennon in jeopardy during his so-called Lost Weekend, she entered a crucial artistic phase in which she benefitted from her temporary separation from Lennon. "I think I really needed some space because I was used to being an artist and free and all that," she later remarked to Sheff, "and when I got together with John, because we're always in the public eye, I lost the freedom. And also, both of us were together all the time." During that period, she had been shifting her experimental music towards a more feminist-oriented rock 'n' roll, as revealed in her 1973 albums "Approximately Infinite Universe" and "Feeling the Space."

Listeners interested in learning more about Ono's work would be well-counseled to sample those records, especially "Approximately Infinite Universe," in which Ono deploys early 1970s rock 'n' roll in the service of an unerring feminist philosophy. This aspect is especially evident in such songs as "Yang Yang" and "Death of Samantha," compositions that ask penetrating questions about the toxic nature of masculinity. This was groundbreaking stuff, particularly during a hyper-masculinized era that wasn't necessarily prepared nor ready to take responsibility for its, at times, emotionally dehumanizing practices.

Love the Beatles? Listen to Ken's podcast "Everything Fab Four."

With these albums, Ono was clearly ahead of her time. She would be on a similar trajectory during the final days of her husband's life, paving the way for one of their final shared triumphs in the form of "Walking on Thin Ice," a poignant, disco-friendly composition that combined a New Wave presence with her philosophical lyrics about the inherently chancy nature of life.

During his final hours, Lennon marveled at Ono's creation, with his wife's eerie vocal sound effects and spoken-word poem sitting deftly alongside his wailing guitar solo. Lennon was ecstatic as he listened to the latest mix of "Walking on Thin Ice." "From now on," he told Ono, "we're just gonna do this. It's great!" — adding that "this is the direction!"

Remarkably, at 40 years old and after nearly two decades of being at the vanguard of pop music, Lennon admitted to only just beginning to glimpse his musical future. And it was Ono, his much-vilified wife, who had led the way for his transformation. In the new century, more than two decades after Lennon's death, "Walking on Thin Ice" would emerge as a chart-topping dance hit and underscore the abiding power of her creative influence. An approximately infinite universe, indeed.

Shares