The recent decision by Governor Ron Desantis (R-FL) to fire the President of New College of Florida, replace the board of trustees, and to abolish diversity equity and inclusion programs in higher education came as a shock even to most conservatives. His actions mark another volley in the "war on wokeness," as he and his right-wing peers call it. Yet to researchers who study the far-right, and those working on university campuses DeSantis' actions reflect the degree to which the right influences academic culture and policy. It may surprise you to know that this is nothing new.

Most Americans hold the view, largely shaped by the media, that college and university campuses are bastions of left-wing ideology. Yet American colleges and universities have long had a prominent conservative contingent — even during the antiwar protest movement of the 1960s. Over time, the work of student movements has been folded into the corporate structure of the institution; this is well-known. Yet most are likely unaware of a new phenomenon occurring across college campuses, in which far-right organizers have sought to use them as a place for contestation, recruitment, and protest/counter protest.

Since 2011, hate crimes on college campuses have sharply risen in the United States. The latest available data, at time of publication, from the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) found a total of 313 cases of white supremacist material on campuses for the 2018-2019 school year. These cases include bomb threats to historically Black Colleges and University, gag orders against teaching, threats to specific scholars, and the weaponization of critical race theory to create controversy over curriculum.

Far right ideology has been mainstreamed largely through online community building and organizing. This often manifests as violence in the real world—such as when conservative pundits Richard Spencer or Milo Yinappplous schedule lectures on campuses and planned marches such as the Unite the Right Rally on University of Virginia campus in 2017, all of which resulted in violent clashes.

This would explain, at least anecdotally, why there are increasing reports from educators (whom we have spoken with) about increasing incidents of racist, sexist, and discriminatory behavior across college campuses. Some of these incidents — like the recent controversy at the University of Missouri where a student used racial slurs in a snapchat message to another students and joked about the murder of three Black University of Virginia student athletes — illustrate the limited power that University administrators have over these kinds of situations.

While administration later condemned the student's post, the University was unable to take disciplinary action under the First Amendment. This is a major area of controversy and contradiction in the contemporary era of the American university—that condemns racial discrimination, yet rarely takes action against racist incidents or confront many systemic issues within the institution.

Students took to social media, first to bring the incident to the administration's attention, and when nothing was done, to express their outrage. Mizzou YDSA (Young Democratic Socialists of America), posted their annotated version of the announcement made by administration.

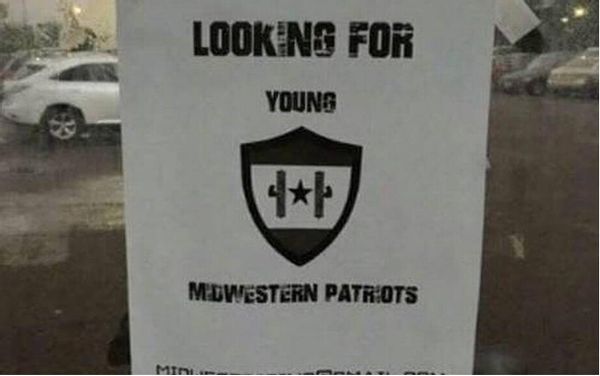

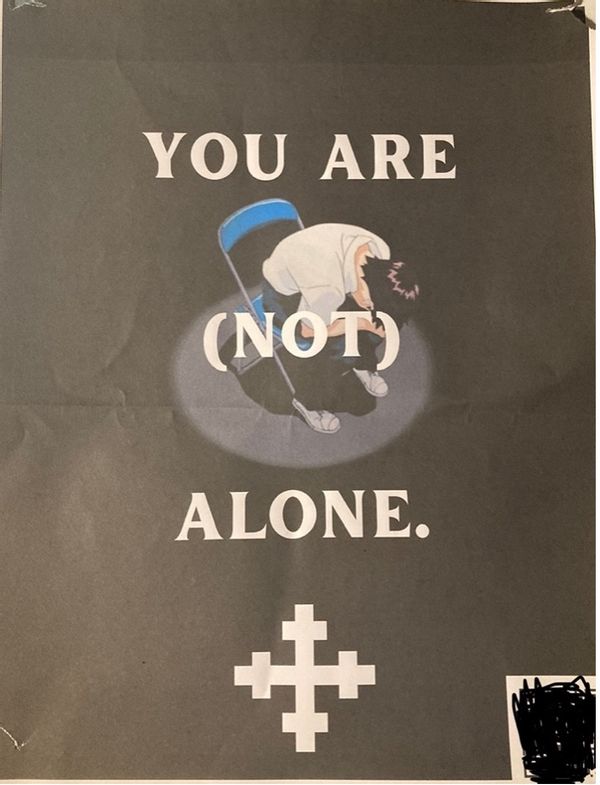

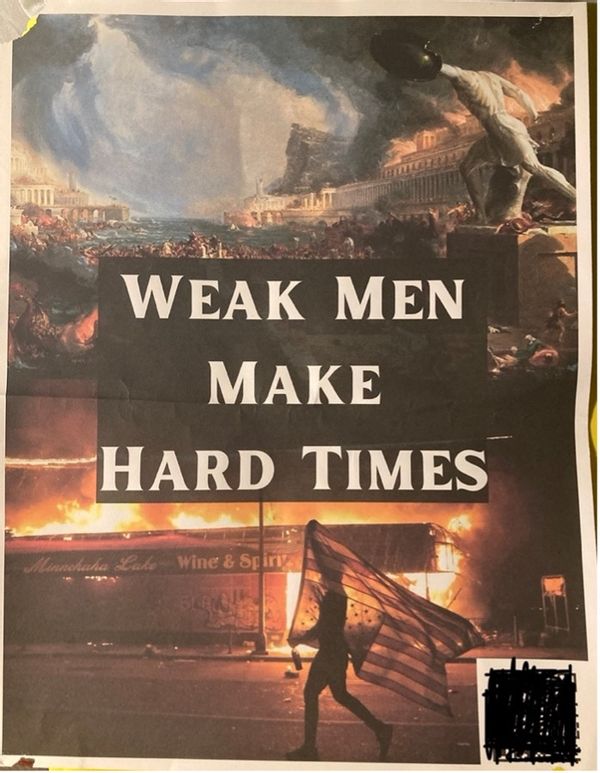

Such incidents are in fact nothing new for college campuses. And,despite conservative accusations that they are being silenced, or censored, empirical studies and experts have shown that this is untrue. While a few anecdotes might be hand-waved away as the work of a few bad apples, our own research on the far right reveals something a bit more deliberate than a leaked electronic communication. The Southern Poverty Law Center tracked recruitment flyers by white nationalist groups from 2016-2017, reporting 329 flyers across 241 college campuses — like the ones below.

(Photo courtesy of AF Lewis)

(Photo courtesy of AF Lewis) (Photo courtesy of AF Lewis)

(Photo courtesy of AF Lewis) (Photo courtesy of AF Lewis)

(Photo courtesy of AF Lewis) (Photo courtesy of AF Lewis)

(Photo courtesy of AF Lewis)

These early observations seem to indicate that far-right groups are initiating the same tactics across university systems. Meanwhile, administrators appear either unable or unwilling to act against these disturbing flyers.

As Vegas Tenold observed in his 2018 book "Everything You Love Will Burn," the demographic of the alt-right that attend universities consists mainly (but by no means exclusively) of "white frat boys [who] could now explain to the world how white frat boys were the true victims of feminism, affirmative action, and other forms of anti-white persecute and could, with a straight face, stand up in public and rejoice in someone finally fighting for their rights as white, affluent college guys." These individuals are often armed with the full strength of their connection to the University, outside online communities, formal organizations with resources, and even the support of some politicians.

As educators we have both seen the ramifications of conservative leadership on higher education. This includes cuts at the state and federal level, but also a retooling of higher education towards a consumer model. The impact on higher education has been an erosion of standards in favor of student retention and satisfaction. While the move to a more "student centered" model has some merits, under conservative leadership it has been weaponized to remove people who disagree with conservative ideology—including those trying to make their students think critically about religion, those with poor teaching evaluations (which are disproportionately women, people of color, and other minorities), or those who would criticize the University.

Want more science and higher ed stories in your inbox? Subscribe to Salon's weekly newsletter The Vulgar Scientist.

While University leadership is unable to challenge the status quo, students are mobilizing to change this system. Some of this is already taking place such as within the University of California school system in which students went on strike over low wages, poor health care, lack of COVID-19 protections, and a variety of other issues. Yet the growth of far-right ideology is a direct result of the University adopted an individualistic "student centered" model of education that is reminiscent of service labor — in which students are seen more as passive consumers of education as a good provided by professors and TAs. The market-oriented understanding of high education feeds into right-wing views of education as a consumer purchase, rather than a social good.

Just as students in the 1960s had to learn how to find their voice, students today are doing the same. However, speaking out on campus can come with consequences. As we write, striking Temple University graduate students are losing their tuition remission, health care coverage, and have one month to pay their tuition bill in full. Perhaps through the actions of these students, and their allies on the ground, a vision of the future that runs counter to that of the alt-right can be more clearly articulated—something the left has failed to do.

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story erroneously referred to New College of Florida as New School University. The story has been updated.

Read more

about higher ed and politics

Shares